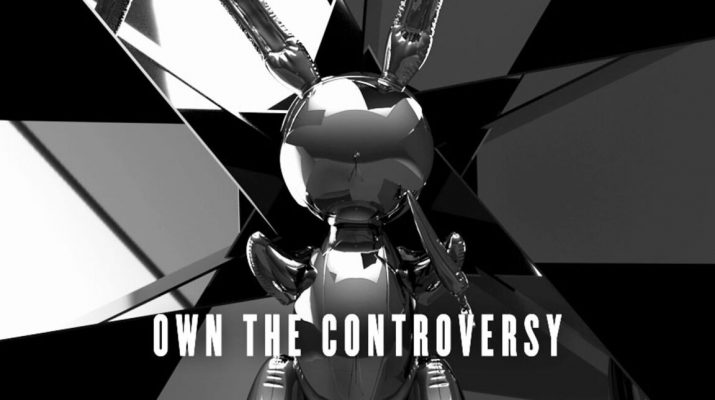

有人认为它欠缺深度、没有收藏价值、是艺术史的一大笑话。也有人认为它充满活力、洋溢欢欣、是一件完美的艺术品。这件杰夫‧昆斯(Jeff Koons)作于1986年的雕塑作品《兔子》(Rabbit)是一件具有开创意义、又极富争议性的作品。这件作品将于5月15日亮相佳士得纽约拍场。

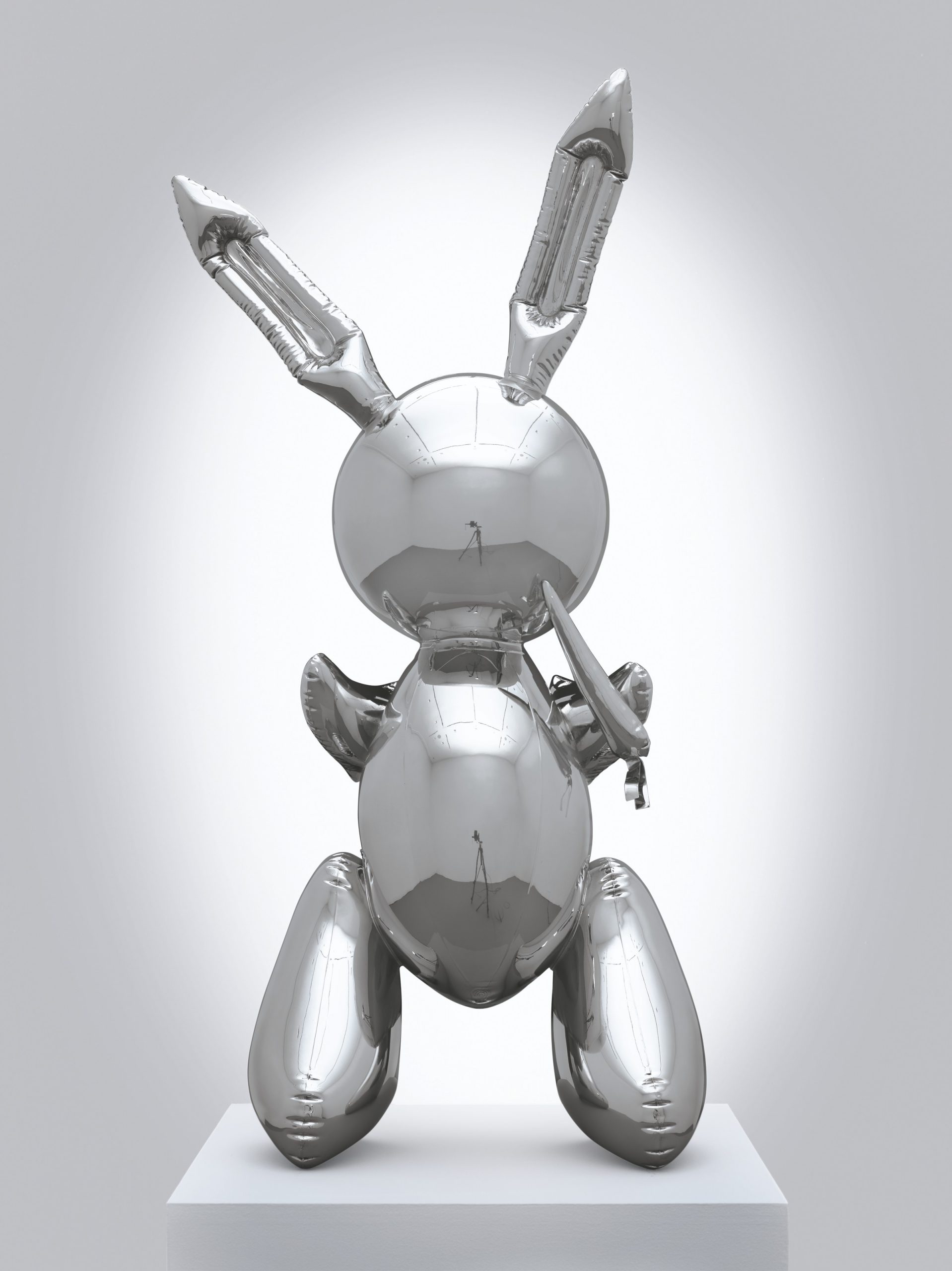

昆斯的《兔子》从33年前诞生至今,一直是二十世纪艺术的经典巨作之一。这件不锈钢雕塑高逾3英尺,集可爱和壮观于一身,同时糅合了极简主义特有的光泽感和卡通形象的趣味性。雕塑的外表简洁而冰冷,却又展现出一种孩童时期的视觉语言;这只没有五官的兔子看起来神秘莫测,整体形态却又憨态可掬。

《兔子》同时期的艺术创作中,具有和它一样高辨识度的作品寥寥无几。它曾多次出现在书籍、展览图录和杂志封面上。2007年梅西百货感恩节巡游中,作品更曾被演化为一个引人注目的巨型充气版兔子,让人过目难忘。

佳士得戰後及當代藝術(晚間拍賣)2019年5月15日

現場拍賣 16977 紐約 SALE 16977

LOT 15 B 杰夫-昆斯 Jeff Koons (生于1955- )不锈钢雕塑《兔子》(Rabbit)

落槌价Price realized USD:$ 91,075,000 (¥9.3亿人民币)

估价Estimate USD:$ 50,000,000 – 70,000,000

Jeff Koons: A Masterpiece from the Collection of S.I. Newhouse

DETAILS

Jeff Koons (b. 1955) Rabbit

stainless steel

41 x 19 x 12 in. (104.1 x 48.3 x 30.5 cm.)

Executed in 1986. This work is number two from an edition of three plus one artist’s proof and is accompanied by a certificate of authenticity signed by the artist.

《兔子》对观者和与之所处的世界来的冲击绝对不容低估。有人视之为一个马虎的笑话,一个与外表不相符的视觉骗局,但也有人欣赏其内在的幽默。《兔子》是结合了众多矛盾的化身——轻与重、刚与柔——而这也正赋予了它最强大的力量。《兔子》在挑衅艺术世界的同时,也拥抱了艺坛的态度和审美观。

1986年,《兔子》在伊莲娜‧松阿本德(Ileana Sonnabend)的纽约画廊首度展出时,《纽约时报》艺评人罗伯尔塔‧史密斯(Roberta Smith)曾这样形容:“巨大的兔子,带着胡萝卜,曾用可充气塑料制造。如今的不锈钢版本的它则把布朗库西(Brancusi)所宣扬的完美形态带入全新意境,尽管它好像把野兔变成了来历不明的外太空入侵者。”著名的博物馆馆长柯克‧华尔涅多(Kirk Varnedoe)将作品比喻为一个里程碑,他在上述展览上首次看见作品时惊讶得“目瞪口呆”。2000年,华尔涅多在为纽约现代艺术博物馆(Museum of Modern Art)策划的“Open Ends”展览中,将《兔子》与布朗库西的作品一同展出。

1987年,亦即《兔子》完成后一年,该作品的版本之一于伦敦萨奇美术馆的“NY Art Now”展览展出,当时前来参观的达明安‧赫斯特(Damien Hirst)还是一个正在学习艺术的年轻学生。他后来忆述道﹕“最初,我无法理解它的简单美态;我震惊了,这只兔子绝对让我大吃一惊。”

这只没有五官的银色兔子得以体现出各种艺术灵感,却又显得冷漠而疏离。当我们面对这只沉默的精钢兔子时,会联想起迪斯尼、花花公子、童年、复活节、布朗库西、路易斯‧卡罗(Lewis Carroll)、法兰克‧卡普拉(Frank Capra)的《我的朋友叫哈维》(Harvey)、马塞尔‧杜尚(Marcel Duchamp)的“现成品”(readymades)系列和安迪‧沃荷(Andy Warhol)的《银云》,却无法为作品赋予单一的意义。

Artist: Jeff Koons (1955 – ) Medium: Porcelain sculpture with chromatic coating

昆斯曾对英国艺评人兼策展人大卫‧塞尔韦斯特(David Sylvester)说﹕“看看这只兔子,它正拿着胡萝卜要放进嘴里。它这个举动是什么意思?它在自渎吗?它是一位正在发表声明的政客吗?它是花花公子标志上的那只兔子吗?……它可能是以上所有这些角色的总和。”

《兔子》想要告诉世人:生活是美好的,所有的品味都是可被接受的,我们更应该接受自己。作品像华丽而充满未来感的偶像般闪闪发亮,它不是专属于王子的镜子,而是留给公众的一面镜子,让它反射出我们的模样,将我们融入它的镜面所展现出的不同情景之中。于是,我们所有人都成为了这个作品的一部分。

“它就像月亮那样反射出光芒。它看似冷漠,其实对你也充满了兴趣。”——杰夫‧昆斯

与昆斯在松阿本德艺廊展出的“雕像”(Statuary)系列中的其他作品相比,《兔子》的成功更让人印象深刻,因为它是该系列中唯的一几乎告吹之作。当灵感来袭之时,昆斯在酒吧的餐巾上画下了10件雕塑中9件的草稿,并希望以该系列作品来剖析由路易十四时期到鲍伯‧霍伯(Bob Hope)时期的社会。但在制作《兔子》时,他却罕有地变得犹豫不决。昆斯向诺曼‧罗森塔尔(Norman Rosenthal)解释道﹕“我在制作不锈钢兔子时,不知道应该制作一只充气兔子,还是一只充气小猪。”

昆斯最后选择了兔子,该作也成为他跻身国际艺坛明星的跳板。其后的“平庸”(Banality)系列也帮助他攀升到了更高的位置,之前被放弃的小猪和《天堂制造》也出现在该系列中。

昆斯似乎把1979年他首个正式的作品系列“充气”(Inflatables)的精髓注入《兔子》之中:一系列的充气玩具被放置于镜子制成的直角底座上,形成一尊独立的雕塑。不过,此作由工匠按照昆斯的严格规格以不锈钢精心打造,突破了充气玩具的短暂性。《兔子》近乎坚不可摧,它并没有暗示死亡,而是反驳死亡。

最重要的是,制作该作品的钢铁材料除了坚固实用,更有着代表奢华的闪烁光芒。昆斯表示﹕“我认为兔子成功的原因在于钢铁材料的表现力完全符合我的原意,这种材料闪亮迷人,让观众在欣赏作品时感到自己很富有,这个效用类似于巴洛克和洛可可时期教堂里的金银色树叶纹饰。兔子所产生的效果是相同的。另外,它就像月亮那样反射出光芒。它看似冷漠,其实对你也充满了兴趣。”

《兔子》呼应了昆斯众多作品中所凸显出的抚慰人心的特质。他经常在作品中探讨社会的流动性,有时会加以评论和批判,但总希望观众能接纳他们自己。

在创作“雕像”系列之前完成的“奢侈和堕落”(Luxury and Degradation)系列中,他研究了酿酒业中的机械原理,并首次在雕塑中运用了不锈钢元素。而在较早期的“平衡”(Equilibrium)系列里,昆斯也探讨了体育运动方面的成功如何推动了社会变革,特别是美国非裔族群的变革。

在“奢侈和堕落”系列成功使用不锈钢后,昆斯在“雕像”系列中进一步探究这种材料的潜力,使它既成为消除不平等的标志,也成为一种刻意带有瑕疵的财富象征。

艺术家解释道:“‘雕像’”系列代表了整个社会的面貌。一方面是路易十四,另一方面是鲍伯‧霍伯。如果把艺术品放在君主手里,它便会服从君主的意志,最终变成装饰品。如果放在大众手里,则会反映大众的自我意识,最终也会变成装饰品。如果放在杰夫‧昆斯手里,便会反映我的自我,最终变成装饰品。”

《兔子》是雕塑,也是昆斯的化身。因为它没有嘴巴,所以不能说话,但它的双耳坚定地指向观众,就像被动而反应敏捷的独裁者,同时也完美地展现了艺术家的矛盾之处,这是他专注探索的意念,也是他的推动力。尽管看似无法说话,《兔子》也可以流畅地传达有影响力的信息,因为它手里的胡萝卜就像是一个麦克风。

它已成为一个符号,引领观赏者展开一段充满联想的无尽旅程。

在创作《兔子》五年后,昆斯向马修‧柯林斯(Matthew Collings)解释说,他视作品为“领袖、演说家的象征,嘴边的胡萝卜象征自渎。我视波普艺术为一场大家可以参与其中的对话。艺术家让大众陶醉于一种自渎行为当中,而不是自我陶醉于艺术主题的自渎行为之中。”

《兔子》也为昆斯最广为人知和深受欢迎的“庆典”(Celebrations)系列买下了伏笔。虽然该作品高度只有三英尺多,但它显然是《气球狗》、《气球花》和于2005至2010年间创作的《气球兔子》的原型。

不过,《兔子》最终也超越了它的极限,它已成为一个符号,引领观赏者展开一段充满联想的无尽旅程,犹如跌入兔窟的爱丽丝,在各种可能的意义中不断探寻。作品并没有确认或否认任何可能得出的结论,它能够让这些观点继续演化,因而占据现今的重要地位。

作品可亲、可爱、富有内涵,也带有波普风格;它有关性爱和死亡、品味和阶级;它探讨乐观、纯真和复制。该作品既探索了艺术家在现代世界的角色,也探讨我们自身的位置。《兔子》反映出我们对于它的内心感受,也彰显了昆斯能以作品引起无限联想的能力。作品多年来所引起的争议无数,更加巩固了它的重要地位。《兔子》以没有五官的空白脸孔,回应(或反射)每个批评。

该雕塑作品铸造于1986年,共有三个版本和一个艺术家试版。除了此作外,另一个版本现藏于洛杉矶布洛德基金会(Broad Foundation),而第三个版本的藏家Stefan T. Edlis和H. Gael Neeson则承诺会把作品捐赠予芝加哥当代艺术博物馆(Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago)。以上两个版本获藏家购藏后,曾在多地展出,但此次拍卖的版本则出自S.I. 纽豪斯(S.I. Newhouse)珍藏,自1988年后便未曾公开展出。

5月15日,佳士得纽约将会于战后及当代艺术晚间拍卖隆重呈献这件满载争议的作品《兔子》,谁将成为兔子的新主人?请拭目以待。

2019年4月17日 (拍卖前 文宣)

Jeff Koons Puppy (vase)

USA, 1998

white glazed porcelain

17½ h × 17½ w × 11½ d in (44 × 44 × 29 cm)

estimate: $7,000–9,000

result: $13,750

This work is number 408 from the edition of 3000 published by Art of this Century. Incised signature, date and number to underside: [Koons ’98 408/3000]. Sold with original box.

provenance: Private collection, Japan

参考:苏富比纽约 现代艺术品拍卖

Contemporary Art Online | New York

21 July 2021•12:00 EDT

40 Jeff Koons Rabbit (Necklace)

杰夫 昆斯 铂金兔子项坠 限量版50之41号

估價:USD $60,000 – $80,000

詳情

Jeff Koons b. 1955

Rabbit (Necklace)

incised with the artist’s signature, dated 05-09 and numbered 41/50 on the underside platinum necklace and pendant in Plexiglas case

3⅛ by 1¾ by 1½ in. (7.9 by 4.4 by 3.8 cm.)

Executed in 2005-2009, this work is number 41 from an edition of 50, plus 5 artist’s proofs.

來源

Gagosian Gallery, New York

Private Collection, California

Thence by descent to the present owner

出版

Olivier Gabet, Bijoux D’Artistes De Calder a Koons. La collection ideale de Diana Venet, Paris 2018, illustrated in color p. 105

E.P. Cutler and Julien Tomasello, Art + Fashion: Collaborations and Connections Between Icons, San Francisco 2015, pp. 112 – 114, illustrated in color

Louisa Guinness, A Decade of Artist’s Jewellry, London 2013, pp. 76, 114

“Picasso to Koons: Artist as Jeweler,” Artforum, September 2011

Julie Brener, “Art Talk: Those Lips, Those Eyes,” ArtNews, December 2005, p. 40

展覽

New York, Museum of Art and Design, Picasso to Koons: Artist as Jeweler, September 20, 2011- January 8, 2012

London, Louisa Guinness Gallery, Jewelry Made by Contemporary Artists, 2012 (color ill.)

相關資料

Jeff Koon’s Rabbit (1986) is not only the defining masterpiece of the artist’s celebrated career but it is also one of the most significant sculptures in the history of art. When Rabbit sold at Christie’s in 2019 for $91 million, it became the most expensive work of art by a living artist, thereby confirming its undisputable cultural significance. Since its creation, Rabbit, which has been endlessly exhibited and theorized, has become one of the essential symbols of contemporary art as well as a kind of totem of our age. There is something perfectly Koonsian about the translation of Rabbit into a necklace, since Koons has, throughout his career, interrogated the relationship between consumer culture and art often by celebrating the everyday objects we are wont to disregard by elevating them to the status of art. For example, in his seminal series, The New, Koons enshrined Hoover and Shelton vacuum cleaners in plexiglass boxes such that they took on a spiritual power, just like the inflatable rabbit does in the current work. However, whereas Koons transformed consumer products into art objects in The New, with Rabbit (Necklace), Koons returns the inflatable to its original status as a consumer good. But for Koons, this line between consumer goods and the realm of art is a faint, and perhaps nonexistent, one. By translating Rabbit into a necklace, Koons emphasizes Rabbit’s divine presence as well as its commodification. The gleaming, platinum rabbit, which suggests a religious pendant, thus becomes the god of our contemporary consumer culture.

附录: 佳士得纽约,不锈钢兔子 拍卖文宣:

PROVENANCE 收藏记录

- Sonnabend Gallery, New York

- Private collection, New York

- Gagosian Gallery, New York

- Acquired from the above by the present owner, 1992

LITERATURE 相关文章:

略

EXHIBITED 相关展览:

略

Lot Essay 说明:

Since its creation in 1986, Jeff Koons’s Rabbit has become one of the most iconic works of 20th-century art. Standing at just over three feet tall, this shiny steel sculpture is at once inviting and imposing. Rabbit melds a Minimalist sheen with a naïve sense of play. It is crisp and cool in its appearance, yet taps into the visual language of childhood, of all that is pure and innocent. Its lack of facial features renders it wholly inscrutable, but the forms themselves evoke fun and frivolity, an effect heightened by the crimps and dimples that have been translated into the stainless steel from which it has been made. Few works of art of its generation can have the same instant recognizability: it has been on the cover of numerous books, exhibition catalogues and magazines; a monumental blow-up version even featured in the 2007 Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade. For an artist such as Koons, who is so focused on widening the sphere in which art operates and communicates, Rabbit is the ultimate case in point.

Despite its endemic presence in our cultural fabric, Rabbit is also an exceedingly rare object. The sculpture was cast in 1986 in an edition of three, plus an artist’s proof. In addition to this example, one is now in The Broad Art Foundation, Los Angeles, another in the collection of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, and a third in the National Museum of Qatar. Thus, the present example is the only one left in private hands, and while other examples have been exhibited extensively, this example of Rabbit has not been exhibited in public since the 1988 group show, Schlaf der Vernunft, or The Sleep of Reason, at the Museum Fredericianum in Kassel.

Looking at Rabbit, the precision for which Koons has since become so renowned is there in all its seductive glory. The steel surface of the titular bunny initially appears smooth and balloon-like, the forms reduced to some abstract, Platonic ideal. They nonetheless introduce complex plays of form, with the narrow carrot serving as a counterpoint to the rounded torso and face. Adding a dynamism to the composition, the tentatively-hovering carrot, perching at the edge of the spherical head also ensures that there is a tension to the work. It hints at penetration, at bursting the balloon, and at that most Koonsian of subjects: sex. The dynamism of Rabbit is reinforced by the fact that, on closer inspection, this sculpture has been rendered with an incredibly meticulous attention to detail. Be it in the corrugations that run up the bending ears, the seams that run down the body, the trails of sheet metal that sprout from the bottom of the carrot or the letters around the nozzle on the reverse, there is an incredible range of textures at play. These are made all the more dramatic by the mercury-like perfection of the bulk of the surface which they disrupt and emphasize. Its curving, sloping surfaces reflect the viewer, yes, but also reflect itself. In this, entire games of light and movement are invoked, with aspects of the rabbit’s anatomy reflected in its head, in its torso and even in the carrot, creating a veritable hall of mirrors.

It is hard to underestimate the cultural impact of Rabbit—both on artists and critics, and the wider viewing public. When it was first shown at Ileana Sonnabend’s gallery in New York in 1986, the art critic of the New York Times, Roberta Smith, described this “oversize rabbit, with carrot, once made of inflatable plastic. In stainless steel, it provides a dazzling update on Brancusi’s perfect forms, even as it turns the hare into a space-invader of unknown origin” (R. Smith, “Art: 4 Young East Villagers at Sonnabend Gallery,” New York Times, 24 October 1986, reproduced online). The respected Museum of Modern Art curator Kirk Varnedoe would describe it as a milestone, recalling that he was “dumbstruck” when he first saw it at the Sonnabend exhibition (K. Varnedoe, “Milestones: 1986: Jeff Koons’s Rabbit,” ArtForum, Vol. 41, No. 8, April 2003, reproduced online at www.artforum.com). In 2000, Varnedoe curated Open Ends at MoMA, juxtaposing Rabbit with Brancusi’s own works. In 1987, the year after Rabbit was made, a cast was featured in the Saatchi Collection’s NY Art Now in London; Damien Hirst, then a young art student, would see it, later recalling, “I couldn’t get my head around its simple beauty at first; I was stunned, the bunny knocked my socks off” (D. Hirst, quoted in G. Wood, “The Wizard of Odd,” Observer, 3 June 2007, reproduced online at www.theguardian.com). And when Louise Lawler made the photograph Foreground in collectors Stefan Edlis and Gael Neeson’s home, it was the side view of the sidelined Rabbit that added to the pointedly understated visual drama, disrupting the Mondrian-esque geometry of the interior.

Kirk Varnedoe’s article in ArtForum, recalling his impression of the Rabbit when he saw it in 1986, exemplifies the incredible iconic intensity with which Koons managed to imbue his sculpture. Varnedoe runs through a catalogue of allusions and implications. After all, this faceless quicksilver rabbit manages to embody whole ranges of references while at the same time remaining deadpan and aloof. We find ourselves filling its steely silence with thoughts of Disney, Playboy, childhood, Easter, Brâncu?i, Lewis Carroll, Frank Capra’s Harvey, Marcel Duchamp’s readymades, Andy Warhol’s Clouds… The Rabbit manages to invoke all of the above, without ever plumping for a single meaning. “Look at the Rabbit,” Koons said to David Sylvester. “It has a carrot to its mouth. What is that? Is it a masturbator? Is it a politician making a proclamation? Is it the Playboy Bunny?… it’s all of them” (J. Koons, quoted in D. Sylvester, Interviews with American Artists, London, 2002, p. 342). If not for Rabbit, Koons said he would have called it The Great Masturbator after Salvador Dali’s painting. Rabbit is what the viewer brings to it. “I’ll be your mirror,” breathed Nico in the eponymous Velvet Underground track a couple of decades earlier, at the height of their collaboration with Warhol. “Reflect what you are, in case you don’t know… I find it hard to believe you don’t know / The beauty you are.” Rabbit echoes this sentiment: it is a hand—albeit an authoritative one—held out in support for the viewer. It tells us that life is good, that all tastes are acceptable, that we should be at one with ourselves. Gleaming like some luxurious futuristic idol, it is a mirror not for princes, but for the public, reflecting us, incorporating us within the ever-shifting drama that plays out on its surface. We are all embraced by this totem.

The success of Rabbit, more than any of the other works in the Statuary series that Koons had shown at the Sonnabend Gallery, is all the more impressive considering it was the only sculpture in the group that was almost not made. When, in the wake of his Luxury and Degradation show, Koons had been asked to contribute works for a group show alongside painters Ashley Bickerton, Peter Halley and Meyer Vaisman, he had been struck in a moment of inspiration and had sketched out—on a bar napkin—ideas for nine of the ten sculptures that would give an idea of the cross-section of society. There is Louis XIV at one end, Bob Hope at the other, with Cape Codder Troll and Doctor’s Delight in between. Yet for Rabbit, there is a rare note of indecision. “When I made my stainless steel rabbit, I really couldn’t decide whether to make an inflatable rabbit or an inflatable pig,” Koons explained to Norman Rosenthal. “I would stay up at night. I have drawings from around that time where I have written down, ‘Shall I do the rabbit or the pig?’ I would inflate the originals and look at them, and I couldn’t decide. ‘Shall I make the inflatable rabbit, or shall I make the inflatable pig? I like both.’ Economically, I could only make one of them at a time, and I chose the rabbit” (J. Koons, quoted in N. Rosenthal, Jeff Koons: Conversations with Norman Rosenthal, London, 2014, p. 135). The show was a hit, with the artists—dubbed ‘The Hot Four’—fêted in the press and in art world circles. Fueled in no small part by the positive reception of Rabbit, it was a springboard to Koons’s international recognition, which would reach new levels with his subsequent series, Banality—in which the jilted pig made its own resurgent appearance—and Made in Heaven.

In his recollection of the dilemma he endured, Koons mentions inflating the originals. In the case of Rabbit, this was a callback to his first ‘official’ series of works, the Inflatables of 1979. In this series, a group of inflatable toys were shown on plinths made of right-angled mirrors, most of them flowers. The mirrors were themselves inspired by Robert Smithson’s works. In Rabbit, Koons appears to have fused the DNA of the inflatable toy and its mirror support from 1979, creating a single sculpture. The shape has changed from the original one shown in Inflatable Flower and Bunny: its legs and torso are more bulbous, making it at once cuter—and more phallic. This emphasizes its links to the pared-back aesthetic of the revered Romanian sculptor, Constantin Brâncu?i, who would distill forms down to their barest essence. In his Male Torso, for instance, there is just the inverted Y form of three cylinders—a body and two legs; in Princess X,

the eponymous subject has been converted into what viewers and critics have repeatedly seen as an arcing penis and testicles—her head and breasts reduced to an incredible level of abstraction.

In truth, Koons has carefully worked to avoid accusations of over-abstraction in Rabbit. The wrinkles and creases of the inflatable original have been carefully crafted in steel, giving it a visceral link to the original object while instilling a heady sense of vulnerability. These ripples—themselves prefigured in the bronze version of Brancusi’s Princess X—create plays of light. Like the hanging strips of metal indicating the original plastic ‘leaves’ of the carrot in the bunny’s hand, they also serve as a covenant, inextricably linking Rabbit to its humble origin as a plastic blow-up toy. Thus, while serving as a textural counterpoint, adding a visual drama and dynamism to the ovoid and spherical forms that dominate the composition, they primarily function as minutely-observed details. In this way, Koons subtly insists that this is not a work of abstraction, but instead one of hyperrealism.

In this sense, the ephemeral nature of the inflatable has been transcended: transformed into stainless steel by artisans working to Koons’s famously-exacting specifications, Rabbit is nigh on indestructible. This is not an intimation of mortality: it is a refutation of it. The vulnerable plastic of the inflatable has been reinforced through Koons’s deft intervention. Stainless steel was a material to which Koons had turned in his previous series, Luxury and Degradation, creating works such as his Jim Beam – J.B. Turner Train, Pail and Baccarat Crystal Set. These were all objets trouvés—found objects—that were then transmogrified by being rendered in shiny steel.

Steel is at once a practical, even proletarian material—one with which Koons had long associations, having been raised in York, Pennsylvania, a small city which prospered in part because of the local steel industry. Crucially, as well as being strong and useful, stainless steel also has the gleam and glimmer of luxury. “I think the Bunny works because it performs exactly the way I intended it to,” Koons said of Rabbit. “It is a very seductive shiny material and the viewer looks at this and feels for the moment economically secure. It’s most like the gold- and silver-leafing in church during the baroque and the rococo. The bunny is working the same way. And it has a lunar aspect, because it reflects. It is not interested in you, even though at the same moment it is” (J. Koons, quoted in A. Haden-Guest, “Interview: Jeff Koons,” pp. 12-36, A. Muthesius (ed.), Jeff Koons, Cologne, 1992, p. 22). In this way, Rabbit and its fellow sculptures in Statuary paved the way for the aesthetic that would see Koons continue to evoke the visual theatrics of European church interiors in Banality and Made in Heaven.

Rabbit, then, ties into the general wave of reassurance that lies at the heart of many of Koons’s works. He has often pointed towards social mobility, sometimes commenting upon it, sometimes critiquing it, but always insisting that the viewers accept themselves for themselves. Thus, in Luxury and Degradation, the series that immediately preceded Statuary, he explored the mechanics of the alcohol industry and the way they tap into and manipulate people’s aspirations in order, ultimately, to peddle booze. It was in this series that Koons had first invoked stainless steel in his sculptures, hinting at both its democratic side, and the fact that it is not a precious metal, however utilitarian it may be. Earlier, in Equilibrium, Koons had explored the way that success in sports was explored and exploited as a vehicle for social change, especially in the African American community. Crucially, he was pointing out the irony both of the slender hope of salvation through basketball, and the fact that he himself, as an artist, was using these images as a rung in the ladder as he carried on in his own upward trajectory through the art world. This was the commodity culture of the contemporary art scene laid bare. Yet the suspended basketballs and the bronze Aqualung alike also acted as promises of support, of salvation.

Building on the success of its use in Luxury and Degradation, in Statuary, Koons explored to greater depths the ability of stainless steel to serve both as a leveler and as a deliberately flawed signifier of wealth. “Statuary presents a panoramic view of society,” Koons explained. “On the one side there is Louis XIV and on the other side there is Bob Hope. If you put art in the hands of a monarch, it will reflect his ego and eventually become decorative. If you put it in the hands of the masses, it will reflect mass ego and eventually become decorative. If you put art in the hands of Jeff Koons, it will reflect my ego and eventually become decorative” (J. Koons, quoted in H. Werner Holzwarth (ed.), Jeff Koons, Cologne, 2009, p. 224).

The various elements in Statuary occupy places across the strata of society and taste: from the inflatable toy of Rabbit to the old-school humor of Bob Hope to the extravagance and decadence of France’s ‘Sun King’ to the titillation of Doctor’s Delight, and so on… The objects range from treasures to gewgaws and everything in between. Koons ceased to use readymades in the series that followed, yet he continued to explore their aesthetic in his own works, creating confections which deliberately invoked kitsch in Banality and Made in Heaven. In the latter series, sculptures of flowers, cherubs and puppies were paired with others showing Koons making love to his then-wife in a series of lavishly explicit photographs, with some of their sex acts celebrated in three dimensions, on large scale, in materials such as polychrome wood, marble and glass. Koons was encouraging his viewers not to allow the structures and strictures of taste to keep them down, but to indulge their guilty pleasures, and indeed expunge any sense of guilt in the first place. As he has explained, “Art is a form of self-help that can instill a sense of confidence in the viewer” (J. Koons, quoted in R. Koolhaas & H.U. Obrist, “Interview,” pp. 61-84, Jeff Koons: Retrospective, exh.cat., Oslo, 2004, p. 61).

It is this self-help aspect that makes stainless steel such a perfect material for Rabbit and its fellow works. As Koons explained, “Polishing the metal lent it a desirous surface, but also one that gave affirmation to the viewer. And this is also the sexual part – it’s about affirming the viewer, telling him, ‘You exist!’ When you move, it moves. The reflection changes. If you don’t move, nothing happens. Everything depends on you, the viewer. And that’s why I work with it. It has nothing to do with narcissism” (Koons, quoted in I. Graw, “‘There Is No Art in It’: Isabelle Graw in Conversation with Jeff Koons,” pp. 75-83, M. Ulrich (ed.), Jeff Koons: The Painter, exh. cat., Frankfurt, 2012, p. 78). Rabbit, then, embraces the viewer in its reflective surface. Like the tree in the forest, it is activated by our presence.

As a sculpture, Rabbit is Koons’s avatar. It stands in for Koons specifically, and for the artist in general, a miniaturized authority figure on a plinth. Mute with its ‘mouthlessness,’ but with its ears firmly pointed towards us, Rabbit is a passive, responsive dictator, perfectly encapsulating the contradictions of the role of the artist that preoccupy and drive Koons himself. It is nonetheless powerfully eloquent, its carrot reminiscent of a microphone. As he explained to Matthew Collings only half a decade after Rabbit was created, Koons saw Rabbit as a symbol of “being a leader, an orator, the carrot to the mouth is a symbol of masturbation. I see Pop art as feeding people a dialogue that they can participate in. Instead of the artist being lost in this masturbative act of the subjective, the artist lets the public get lost in the act of masturbation” (J. Koons, quoted in M. Collings, “Jeff Koons Interviewed by Matthew Collings,” pp. 39-47, A. Papadakes (ed.), Pop Art Symposium, London, 1991, p. 42).

Rabbit stands out from the Statuary crowd, as it also prefigures what has since become one of Koons’s best-known and best-loved series of works: Celebration. Rabbit may only be three and a bit feet tall, but it is a clear ancestor of Balloon Dog, Balloon Flower and its sister-works—as well as the subsequent Balloon Rabbit of 2005-10. In this, it taps into one of the most recurrent themes in Koons’s work: the role of air or breath as a representation of life. Explaining this with reference to the pool toys so meticulously reproduced in painted for his series, Popeye, Koons stated, “When you take a deep breath, it’s a symbol of life and of optimism, and when you take your last breath, that last exhale is a symbol of death. If you see an inflatable deflated, it’s a symbol of death. These are the opposite” (J. Koons, quoted in J. Peyton-Jones & H.U. Obrist, “Jeff Koons in Conversation,” pp. 67- 75, Peyton-Jones, Obrist & K. Rattee (ed.), Jeff Koons: Popeye Series, exh. cat., London, 2009, p. 71). Be it in the early Inflatables, in the vacuum cleaners shown in his earlier series The New, in the bronze boats and diving equipment of Equilibrium or the balloons of Celebration, this invocation of breath has been a constant for Koons.

Rabbit, then, transcends its own limitations. It is a signifier that launches the viewer on an endless journey of association, tumbling down a rabbit hole of meaning. It neither confirms nor denies any of the conclusions that may be drawn. It is its ability to leave these ideas hanging that lends it the power that has seen it attain the status it enjoys today. It is approachable, sweet, high-brow, Pop; it is about sex and death and taste and class; it is about optimism and innocence and reproduction. It explores the role of the artist in the modern world, and our own place too. It reflects whatever we bring to it. In this, it reveals Koons’s own ability to create art works that launch a thousand thoughts. It is only too apt that the last time this version of Rabbit was shown in public, over three decades ago, it was in a show entitled The Sleep of Reason. This phrase was taken from one of Francisco Goya’s caprichos, showing a sleeping artist beset by a tumult of beastly chimeras. “The sleep of reason produces monsters,” an inscription on the picture declares. However, Goya’s own explanation is more in tune with Rabbit: “Fantasy, abandoned by reason, produces impossible monsters; united with it, she is the mother of the arts and the origin of marvels.”

佳士得 纽约拍卖

LIVE AUCTION 2791

11 Nov 2013

POST-WAR AND CONTEMPORARY EVENING SALE

LOT 12 Jeff Koons (B. 1955) 橙色 钢塑 气球狗 Balloon Dog (Orange)

落槌价:Price realized USD 58,405,000 (¥4.02亿人民币)

估价: Estimate USD 35,000,000 – USD 55,000,000

Jeff Koons (B. 1955)

Balloon Dog (Orange)

DETAILS

Jeff Koons (B. 1955)

Balloon Dog (Orange)

signed and dated ‘Jeff Koons 1994-2000’ (on the underside)

mirror-polished stainless steel with transparent color coating

121 x 143 x 45 in. (307.3 x 363.2 x 114.3 cm)

Executed in 1994-2000. This work is one of five unique versions (Blue, Magenta, Orange, Red, Yellow).

平庸限制了想象 拍出4亿元的气球狗

在当代艺术思潮中 巨型艺术品往往以其冲击视野的感官效果 成为出众之作 这些“巨作”往往 也成为拍卖行的“爆点” 似乎也更容易拍卖出惊人的价格 不禁让人产生对艺术的误解

艺术品“越大越贵”?

其实 艺术品的价值有着更复杂的评价标准 很多艺术“小”作也不容小觑 巨型艺术品

杰夫·昆斯 气球狗

杰夫·昆斯创作的

橙色巨型装置作品《气球狗》

灵感来源于气球玩具的镜面不锈钢雕塑

气球狗表层无暇犹如镜面

体积宏伟壮观 颜色华丽细腻

它象征着童年的希望与纯真

深受大众及藏家的青睐与追捧

这个10英尺高、体重1吨的艺术品 有蓝色、品红色、金黄色 红色和黄色五种颜色 2013年以5840万美元的 拍卖价 创造了在世界艺术家单品拍卖新纪录 成为世界上目前最昂贵的当代艺术雕塑作品

PROVENANCE

Anthony d’Offay Gallery, London

Acquired from the above by the present owner

LITERATURE

略

SPECIAL NOTICE

略

Lot Essay

Jeff Koons’ Balloon Dog (Orange) is considered the supreme example from the highly acclaimed Celebration series of paintings and sculptures that Koons instigated in the early 1990s. The series evolved from his desire to recreate the ecstatic experiences of a child’s enjoyment of the world through universal signifiers representing birthday parties and festive events. It is one of five unique Balloon Dog sculptures made from precision engineered, mirror-polished stainless steel and finished with a translucent coating of either blue, magenta, orange, red, or yellow. Balloon Dog (Orange)’s radiantly beautiful color and pristine finish embodies a contemporary vision of fin-de-siécle opulence. With its giant swollen body and highly reflective surface, this ten-foot, one-ton metal balloon animal conveys a miraculous illusion of weightlessness. The sheer beauty of its materiality is designed to ensnare and captivate, while its form is endowed with the joyful associations of childhood, hope and innocence. Balloon Dog (Orange) uses sentimentality and hyperbolic scale as a tool of insight-one that speaks directly to and about a collective humanity. Its high-impact size, form, and subject encapsulates Koons’ egalitarian approach to art; and his masterful ability to create intellectually and sensuously exciting objects from the banal and familiar. Content aside, in formal terms Balloon Dog (Orange) marked a new pinnacle of sculpture as an entire medium, discipline and tradition. It is a bold, forceful and imposing monument that radiates powerfully with an almost epic sense of vitality-qualities that have firmly secured its status as one of the defining artworks of the 20th century.

Despite its immense size, no detail has been spared in the rendering of the Balloon Dog’s form: note the exactingly shaped knot that serves as its nose, the twists and crimps at the base of the robust limbs, and the erect, yet rubbery looking tail. The artist’s exacting standards are one of the most captivating aspects of Koons’ work and this trait reached its apogee with the fabrication of the Celebration sculptures, which includes balloon flowers, hanging hearts, eggs, and diamonds, among other subjects. Koons had intended to premier the series at New York’s Guggenheim Museum in the mid-1990s, but it involved so much labor that he was forced to gradually complete it over more than ten years. Part of the challenge was creating the flawlessly smooth contours on sculptures like Balloon Dog (Orange) where 60 parts are welded together to produce the simple, but very suggestive shapes. Koons worked closely with a specialist foundry in California to achieve his desired result, which involved years spent perfecting the meticulous color coating that appears to hover above the stainless-steel surface.

The thousands of hours spent modeling and constructing this sculpture was not caused by obsessiveness on Koons’ part, but rather an uncompromising will to create something faultless for his audience, something that would instill absolute confidence in the object and its purpose. Describing his exceedingly high expectations for the Celebration series, Koons has stated: “I believe in art morally. When I make an artwork, I try to use my craft as a way, hopefully, to give the viewer a sense of trust. I never want anybody to look at a painting, or to look at a sculpture, and to lose trust in it somewhere” (J. Koons, quoted in H. Werner Holzwarth (ed.), Jeff Koons, Cologne, 2009, p. 390). The investment has certainly paid off-Balloon Dog (Orange) has become a Koons masterpiece. The end result is an exceptionally beautiful object with an astonishing visual impression induced by the combination of its immaculate sheen, the flawless, flowing curves and the intricate, navel-like crannies.

For renowned art collector Peter Brant, the chance to add Balloon Dog (Orange) to the collection was an unmissable opportunity, despite the incredibly long wait time he faced before the final work was actualized: “. . .When I first saw the Balloon Dog, I instantly thought, this is so obvious, and so beautiful. I’d known [Koons’] work very well by that time, but it hit you like the perfect sculpture. It’s just so aerodynamic and so Pop and so wonderful. That was early in the 1990s, and I wanted to acquire the piece. But, Jeff hadn’t really come to grips with how to execute the work because when I first saw it, it was in the clay form. It took him eight to ten years to really resolve a lot of the technical logistics” (P. Brant, interviewed by Christie’s, New York, 2013). Each example of the Balloon Dog has a similarly outstanding pedigree; they all belong to an illustrious group of private collectors who have taken an avid interest in the evolution of Koons’ career. Of the other versions, Steven A. Cohen owns Balloon Dog (Yellow); The Broad Art Foundation has Balloon Dog (Blue); Franois Pinault owns Balloon Dog (Magenta); and Dakis Joannou’s DESTE Foundation for Contemporary Art has Balloon Dog (Red).

When the Celebration works eventually started to be shown in museums around the world in 2000, Koons’ reputation as one of the world’s greatest sculptors was immediately renewed and deepened. Over the years, he has explored a whole gamut of sculptural materials, including readymade objects, bronze, porcelain, wood, stainless steel, Murano glass, and even live flowers. It is these three-dimensional forms that find the most enthusiasm as their tangible qualities posses an ability to engage sensual experience in a way that is almost impossible in any other medium. Balloon Dog (Orange) is themed and scaled for collective enjoyment. Its size acknowledges the needs of large audiences as opposed to intimate trophies or ornaments.

The magic attraction of Balloon Dog (Orange) lies in its ability to convey cuteness, power and material perfection. Its alert, four-legged form makes it reminiscent of the heroic equestrian statuary that populates public spaces across the globe. Koons himself has called this piece the “Trojan horse” of the Celebration series: “It’s a very optimistic piece, it’s a balloon that a clown would maybe twist for you at a birthday party. But at the same time it’s a Trojan horse. There are other things here that are inside: maybe the sexuality of the piece” (J. Koons, quoted in F. Bonami (ed.), Jeff Koons, exh. cat., Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, Illinois, 2008, p. 81). The sculpture taps into the mythic not only through its equine appearance and gargantuan proportions then, but also through the somewhat mischievous intent that hides behind its fetishistic exterior. Like the fabled subterfuge that the Greeks used to enter the city of Troy, Balloon Dog (Orange) seems innocent but is in fact loaded with aesthetic and existential challenges. Koons sees sexual connotations in the shiny sculpture as a metaphor for desire. Its super-saturated orange glow is used as a seduction technique to draw us towards its gleaming surface and, as we approach, we cannot avoid seeing the thrill it elicits reflected back at us. It constantly reminds viewers of their existence by returning their gaze and their movements; people activate it, it needs them. Perhaps in establishing this psychological mirror Koons is proposing that it is our emotional and intellectual responses that are the true the concealed soldiers of this Trojan horse. From early on in his career, Jeff Koons has preferred to create his works in discrete, conceptually self-contained series that are grouped under their own titles. Since 1979 when he developed the Inflatables ready-made combines, he has produced at least 20 series, including The New (exhibited in 1980), which integrated references to Minimalism and Pop with their stacked vacuum cleaners and fluorescent tube lighting; Equilibrium, 1985, best known for its sculptures of basketballs floating in tanks; the Statuary series of stainless steel figurines that featured Rabbit, 1986, one of his most celebrated artworks; and Banality, 1988, an ultra-kitsch grouping that includes a life-sized, white and gold porcelain depiction of Michael Jackson and his chimpanzee, Bubbles. With each series produced during the 1980s, Koons’ hotly debated art drew ever-increasing audiences, reaching a crescendo of provocation and controversy when he exhibited Made in Heaven, 1989-1991, a suite that openly explored attitudes towards sexuality through its explicit, if romanticized, imagery. Koons has eschewed standards of “good taste” in art at every turn, introducing unexpected objects and images that acknowledge the goods, colors, emblems and experiences that constitute the normal existence of working and middle class citizens. Koons insists there is no irony in what he does, but his embrace of the quotidian is a calculated effort to undermine hierarchies of culture, and to validate popular taste. Like Andy Warhol’s avowal that Pop art was about “liking things,” Koons says his art is about the liberation and power that comes from embracing the mainstream.

Koons’ work invites us to experience pleasure without guilt, and nowhere is this more obvious than the Celebration series. Where Made in Heaven sought to remove shame from sex, the Celebration works that followed directly after were made to conjure the wonderment, blissful naivety and freedom of childhood. What was originally conceived as a small project has since developed into Koons’ most elaborate series to date, comprising twenty monumental sculptures and sixteen large-format oil paintings. Celebration continued Koon’s interest in notions of the cycle of life. He started the series with the concept to make a calendar featuring various festive images, some of them made from balloons, many of them linked to times of the year such as Valentine’s, Easter, birthdays and the coming of spring-events that he was experiencing anew after the birth of his son in 1992. He began creating simple photo studies of handmade balloon forms and store-bought items that would end up summoning an abundance of new ideas for immaculate, glistening sculptures and hyper-real paintings. “I took my camera and prepared these set-ups,” Koons explained. “I shot some balloon tulips on a reflective background, and I made a balloon dog, again on a reflective background. I bought a hanging heart with some gold ribbon from a shop window I saw on Lexington Avenue, and I photographed a bread with an egg. I shot these different images and soon realized that this was too good, that I had more than a calendar here. I had a whole body of work” (J. Koons, quoted in T. Vischer, “Dialogues on Self-Acceptance: Jeff Koons about Himself and his Work From Conversations with the Artist, New York, Early February 2012, Part I,” in S. Keller and Vischer (eds.), Jeff Koons, exh. cat., Riehen, 2012, p. 34).

Through his intensely bright paintings of a party hat, or a slice of heavily-iced cake, to the brilliantly shiny Balloon Dog or heart-shaped ornaments, Koons hopes to awaken the child that exists inside all of us. The transcendent sense of joy expressed in the Celebration works make them highly idealistic as they deal with “hope, the future and with respect for humanity” (J. Koons, quoted in, Jeff Koons, exh. cat., Kunsthaus Bregenz, 2001, p. 25). This social aspect to art is all-important to Koons. By depicting the world of the child with all the sophistication and technical craftsmanship available to the adult, he appeals to what is good in people. He asks us to recapture that time in our lives before we were indoctrinated into the expectations and value judgments of society, when heaven could be found in a piece of foil-wrapped candy or a cereal-box toy. His goal is to return us to those associations, to that openhearted delightedness, and the vehicles he chooses are simply archetypes of our shared experience. As the pinnacle achievement of the Celebration series, Balloon Dog (Orange) represents one man’s heartfelt conviction that art can offer succor to the masses. Koons wants his work to be as accessible as possible, to break down the segregation between high and low culture so no one is made to feel inferior. This inclusivity, he believes, will ultimately free us from self-imposed constraints: “My work is a support system for people to feel good about themselves and have confidence in themselves-to enjoy life, to have their life be as enriching as possible, to make them feel secure-a confidence in their own past history, so that they can move on to achieve whatever they want” (J. Koons, quoted in H. Werner Holzwarth (ed.), Jeff Koons, Cologne, 2009, p. 456).

As Koons has indicated, Balloon Dog was a key image in the early development of the Celebration series. What else could suggest the jollity of children’s parties more eloquently than a colorful balloon, twisted into the instantly recognizable form of a dog. But immediate recognition does not necessarily imply instant comprehension. There is an ambiguity at play in the conjunction between the expected lightness, vulnerability and elastic quality suggested by the original subject and the palpable rigidity and extraordinary weight of the enlarged facsimile. Like Koons’ early Inflatable and Equilibrium works, Balloon Dog is a symbolic vessel of air, filled with the intangible stuff of life. “I’ve always liked inflatables because they remind me of us. We breathe and we fill up with air and it seems like a commitment of some type. At the same time it’s not a commitment because we exhale right away,” he has said (J. Koons, quoted in H. Werner Holzwarth, op. cit., p. 11). Koons is a brilliant manipulator of materials and his union of an ephemeral object with an immutable metal is not just a way of creating a lasting dazzle of freshness. It is also about the fact of mortality. Balloon Dog (Orange) is a permanent monument to the fleeting and momentary. It will never wither with time, fall victim to a pin-prick, or an overzealous squeeze. The sculpture’s imperviousness to decay provides comfort in a world of perpetual change, while also becoming a sort of mass culture momento mori. Koon’s romantic notion of conveying humanity through the vaguely absurd playthings of our past takes on an even greater poignancy when we consider that Balloon Dog, and the Celebration series in general, was made as a deeply personal tribute to the artist’s young son, whose celebrations and annual milestones he was, for a time, unable to share. As Koons explained, “I was trying to make art that my son could look on in the future and would realize I was thinking about him very much during these times…. that he can look and see my dad’s thinking about me, but to also embed in these things something that is bigger than all of us” (J. Koons, quoted in J. Jones, “Jeff Koons: Not just the king of kitsch,” The Guardian, 30 June 2009, accessed via www.theguardian.com). Balloon Dog (Orange), therefore, speaks of love and of life. Its canine imagery also taps into world’s most ancient emblem of fidelity and unconditional affection. With his interest in all that is commonly perceived as good, it is unsurprising that dogs have been recurring motifs within Koons’ oeuvre. These include porcelain puppies in the Banality series, carved wooden dog figures in the Made in Heaven series, and the vast flower-covered Puppy. Of all these pooches, Balloon Dog achieves the greatest tension between representation and abstraction. It embodies Koons’ aspiration to bring big meanings to simple, easily recognized symbols.

While Koons’ work is sometimes perceived as kitsch, to him, everyday objects embrace aspects of transcendence. He has made Balloon Dog (Orange) as a beacon of benignity in a world of pessimism, confusion and strife. Its high-shine structure is intended to usher in the transition from the banal to the sacred. Our received wisdom tells us that polished metals represent wealth and spiritual enlightenment and Koons knowingly uses stainless steel as a fake reflection of those values. He has often compared his work’s unashamed over-the-topness to lavishly decorated church interiors that communicate to the public that they are in the presence of the divine. “The church uses the Baroque to manipulate and seduce, but in return, it does give the public a spiritual experience” (J. Koons, quoted in A. Muthesius, Jeff Koons, Cologne, 1992, p. 158). The golden luster of Balloon Dog (Orange) is similarly designed to manipulate its viewers and it has an immaculacy that verges on the spiritual, as is only appropriate for an artist so concerned with almost religious subjects such as innocence, procreation, and the heavenly. The sculpture’s gloriously warm hue may belong to the secular domain of art history, for instance Warhol’s revered Orange Marilyn of 1964, but it can additionally be linked to faiths across the world, from Pomona, the Roman goddess of fruitful abundance, to the robes worn by monks and holy men across Asia.

This is a sculpture firmly bound to the emotive Romantic tradition in art, but with a very contemporary twist. The grandeur of its size, the mesmerizing color and majestic surface of Balloon Dog (Orange) all draw on the concept of the sublime. Koons has transfigured the real and familiar into something extraordinary and otherworldly, creating a kind of Platonic ideal of a balloon dog-a manifestation of the holy. André Breton once said that when one releases things from their original contexts, latent or additional meaning rise up to the surface of consciousness. This work of art has chameleon-like qualities; its reflective surface is capable of physically changing with its surroundings and its many-layered meanings make it conceptually change in the mind of each viewer. While Koons’ tactics may recall the Surrealists’ methods of transforming the commonplace into the strange and exotic via the metamorphosis of scale and materials, he does not seek to disturb the viewer or make his subject uncanny. Instead he accommodates people’s desires and offers them security and comfort, avoiding, or at least masking, the darker sides of the subconscious with bright and playful imagery. Koons’ Balloon Dog uses humorous means for serious ends, affirming viewers’ faith in themselves and the profound beauty of life itself through an overriding message of optimism.

![[临渊阁]天地一家春](https://www.antiquekeeper.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/BW-Erping-1a-17-6-1.jpg)