Description

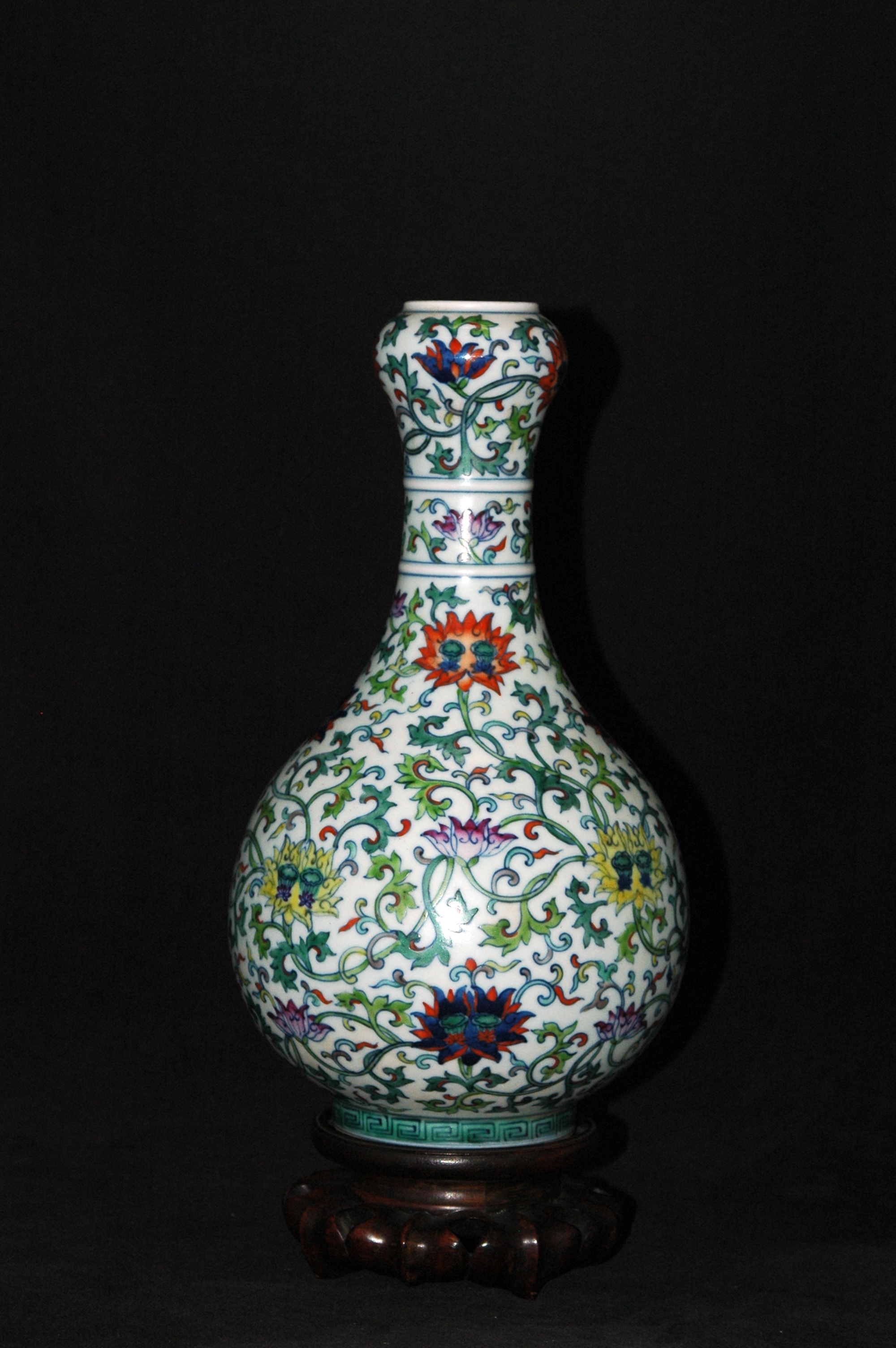

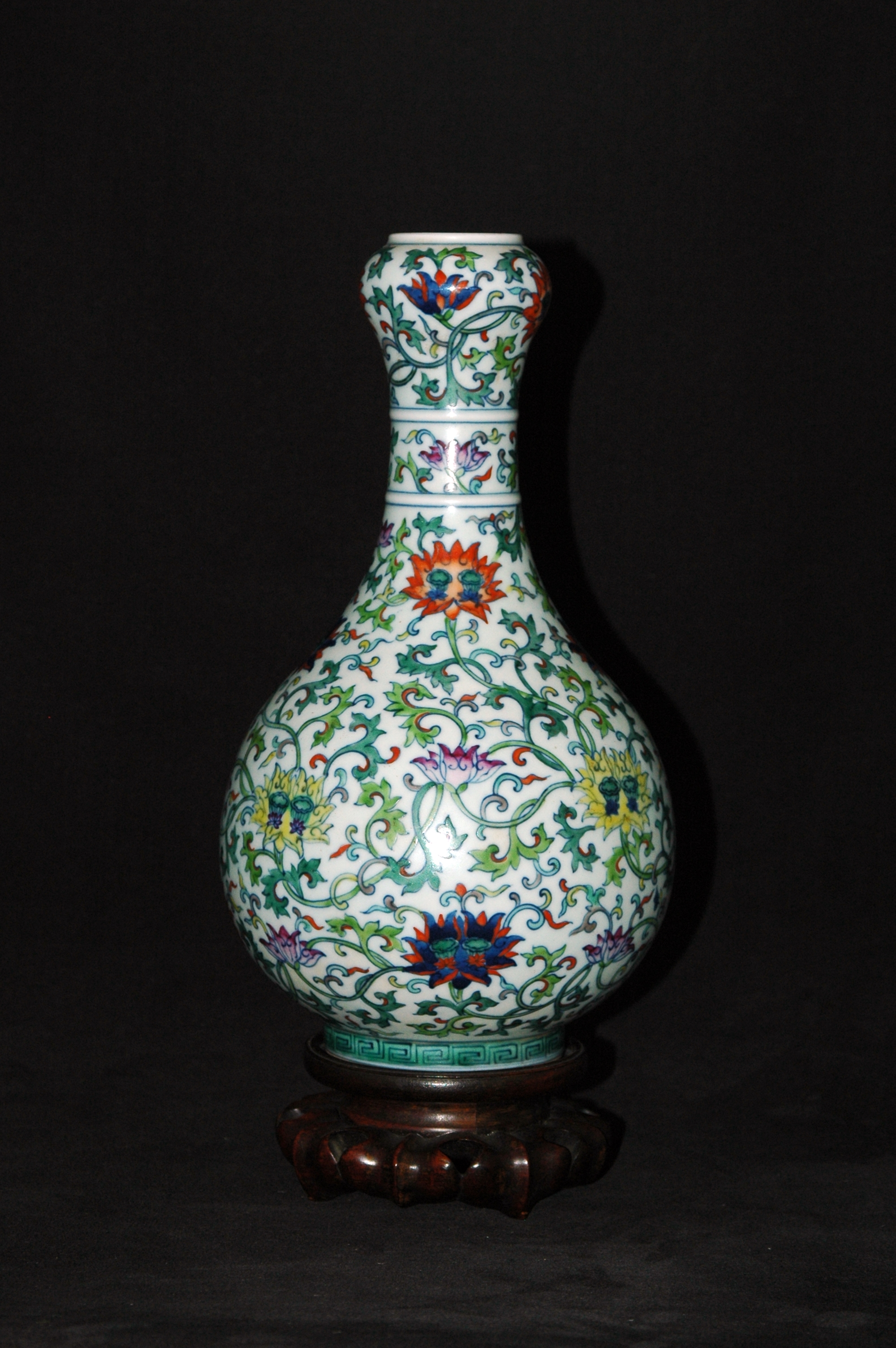

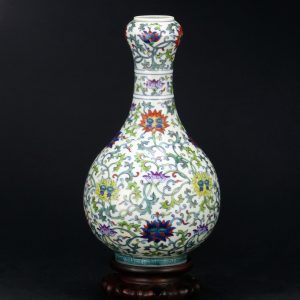

乾隆款 斗彩缠枝莲蒜头瓶

粉彩,珐琅彩

参考:苏富比 22

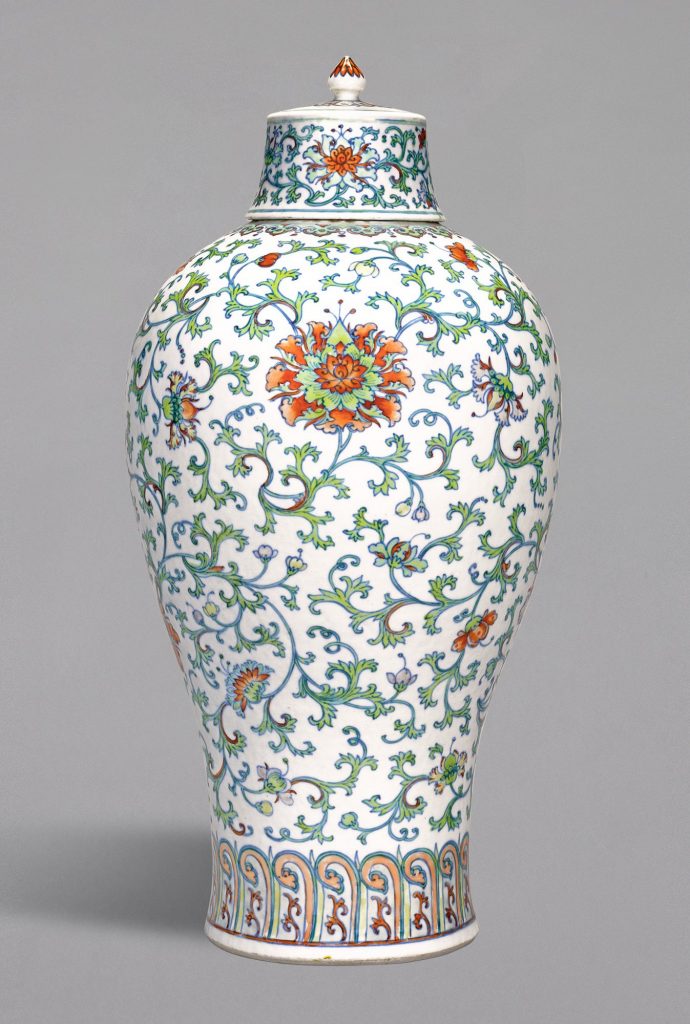

清十八世紀 闘彩纏枝花卉紋梅瓶連蓋

A RARE LARGE DOUCAI ”FLORAL’ MEIPING AND COVER, QING DYNASTY, 18TH CENTURY

Estimate: 80,000 – 120,000 GBP

Description

A RARE LARGE DOUCAI ”FLORAL’ MEIPING AND COVER

QING DYNASTY, 18TH CENTURY

清十八世紀 闘彩纏枝花卉紋梅瓶連蓋

sturdily potted with a tapering body elegantly rising to a broad rounded shoulder and surmounted by a short waisted neck, the voluptuous body wreathed with prominent floral blossoms borne on stylised foliage issuing further colourful blooms and buds between a band of ruyi heads and elongated lappet border, the neck rendered with a row of ruyi heads collaring the mouth and stylised lappet border together with a narrow band of composite scrolls skirting the foot, the well-fitted cover similarly decorated with flower scrolls and embellished with stylised lappets radiating from the lotus bud finial on the slightly domed top

Height 46.7 cm, 18⅜ in.

Condition Report

There is a vertical 4cm., hairline rim crack to the vase and very light glaze scratches around the body, and a circa 5cm., hairline rim crack to the cover and minor rim fritting.

口沿見一細沖(約4公分),器身釉彩有少許極輕微劃痕,瓶蓋一約5公分細沖,口沿有少許毛口。

Catalogue Note

Notable for its generous proportions and finely painted feathery scroll in doucai enamels, meiping of this type are rare and no other closely related example appears to have been published. The floral scroll was masterfully executed, with each bloom and flowering bud skillfully painted as viewed from a different angle, thus creating a sophisticated and yet uncontrived design.

A slightly smaller meiping and cover with a dragon against a similarly rendered flower scroll, from the Qing Court collection and still in Beijing, is illustrated in The Complete Collection of Treasures in the Palace Museum. Porcelains in Polychrome and Contrasting Colours, Hong Kong, 1999, pl. 237; and one lacking the cover and painted with bajixiang, from the collection of Gordon Cummings, was sold at Christie’s New York, 3rd June 1988, lot 313.

This vase echoes in multiple ways the celebrated porcelain tradition of the Ming dynasty (1368-1644); the doucai colour scheme, whereby the outlines of the design were first painted in underglaze blue and later filled in overglaze enamels, references the Chenghua reign (r. 1465-1487), when the quality of doucai porcelain was at its peak. Its rendering of the floral blooms and feathery scroll, as well as the decorative band at the foot, on the other hand recall porcelain designs of the early Ming period. A Yongle (r. 1403-1424) period meiping, of much smaller size, painted with lotus buds and blooms, in the National Palace Museum, Taipei, was included in the Museum’s exhibition Radiating Hues of Blue and White. Ming Dynasty Blue-and-White Porcelains in the National Palace Museum Collection, Taipei, 2016, cat. no. 15; and a reconstructed meiping with a Xuande mark and of the period, painted with dragons above a similar band at the foot, recovered from the waste heaps of the Ming imperial kiln site in Jingdezhen, is illustrated in Imperial Porcelains from the Reign of Xuande in the Ming Dynasty, Beijing, 2018, pl. 61.

本瓶編制龐大,闘彩紋飾秀麗,此類梅瓶甚為珍罕,據現時記載並無他例可比。本瓶番蓮紋飾精工繪製,或繪花兒盛開,或描含苞待放,角度每朵不一,構圖雅緻而不過份工整。比較一例,尺寸較小,瓶蓋飾龍紋,清宮舊藏,現存於北京,圖載於《故宮博物院藏文物珍品大系.五彩.鬪彩》,香港,1999年,圖版237;另比一例,無蓋,八吉祥紋飾,出自Gordon Cummings收藏,售於紐約佳士得1988年6月3日,編號313。

本瓶以明代珍瓷為藍,從數處可見:鬪彩紋飾,先施釉下青花,後上釉上彩,而成化鬪彩,誠屬至臻;瓶身施纏枝番蓮紋,近足處環施紋飾,屬於早明瓷器紋飾風格。台北故宮博物院收藏一件永樂梅瓶例,尺寸遠小於本品,繪蓮花及花苞,曾展於《藍白輝映:院藏明代青花瓷展》,台北,2016年,編號15;另比一重組梅瓶例,宣德年器並款,繪龍紋,近足處環紋與本品相近,出土自景德鎮明代御窰遺址,圖載於《明代宣德御窑瓷器》,北京,2018,圖版61。

参考: 苏富比 3676

中國藝術珍品

清乾隆 鬪彩番蓮紋八吉祥罐

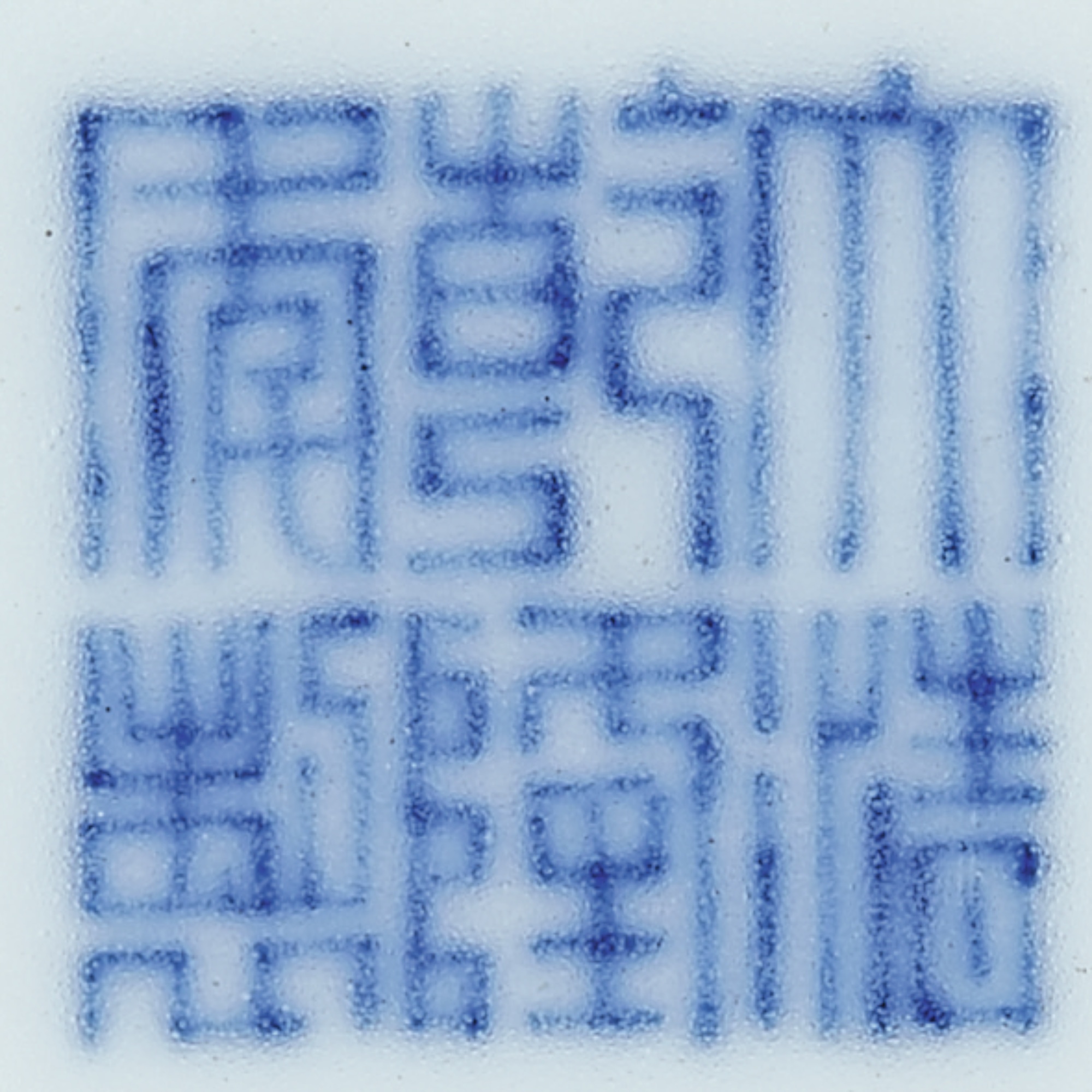

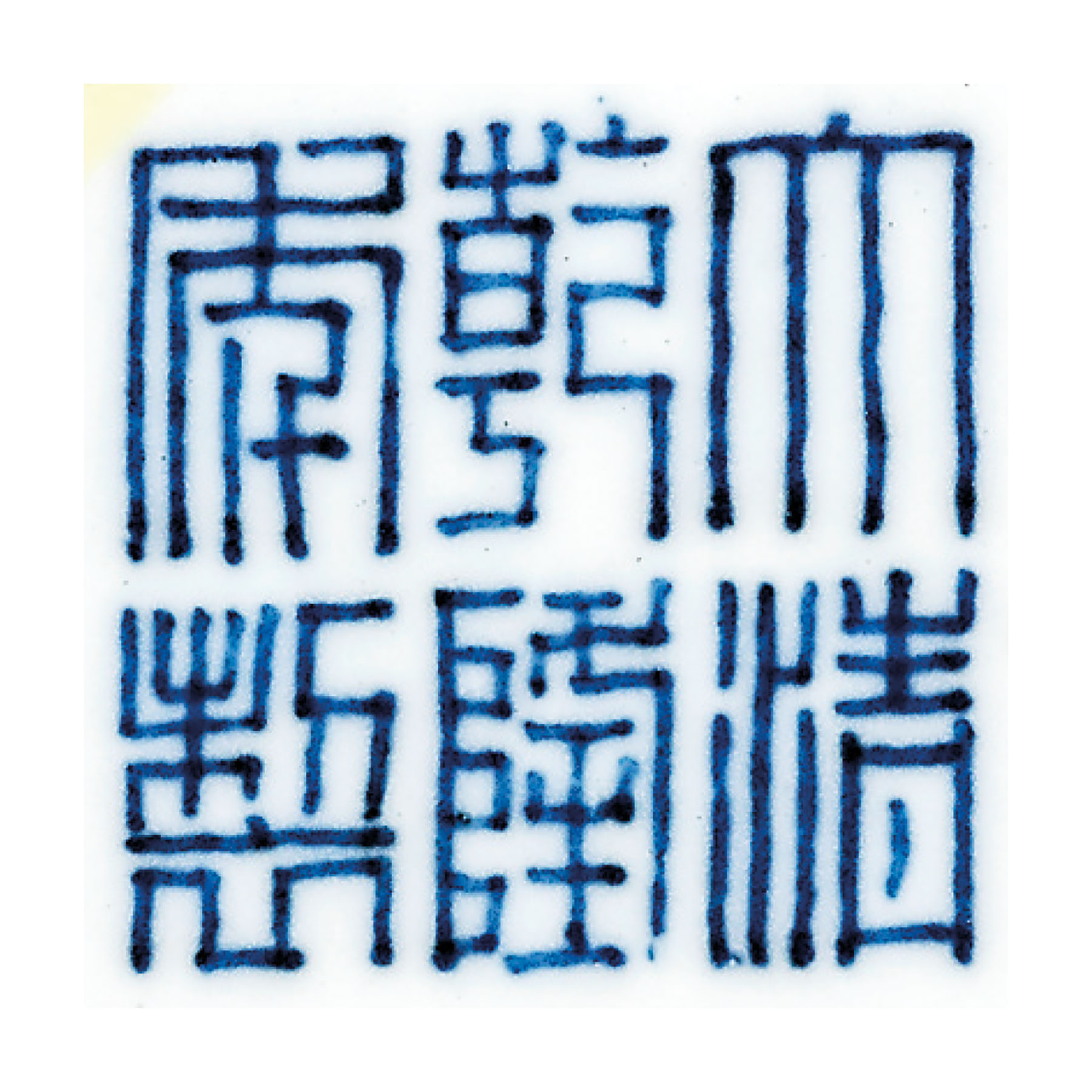

《大清乾隆年製》款

《大清乾隆年製》款

《大清乾隆年製》款

1,200,000 — 1,800,000港幣

拍品已售 1,625,000 港幣 成交價 (含買家佣金)

拍品詳情

清乾隆 鬪彩番蓮紋八吉祥罐

《大清乾隆年製》款

11.3 公分,4 3/8 英寸

相關資料

此雅器仿古,繪八吉祥纏枝番蓮紋,實為罕見,其紋飾巧思,源可溯成化鬪彩纏枝蓮托八吉祥蓋罐,成化例可參見《景德鎮出土元明官窰瓷器》,北京,1999年,圖版327。

乾隆帝鍾愛吉祥紋飾,其年間所製器物紋飾,多為不同樣式傳統吉祥紋演變而來。其源可上溯傳統八吉祥如意花卉紋,並以新穎的方式呈現。

中國藝術珍品

2016年10月5日 | 下午 2:30 HKT

香港

参考:佳士得拍賣 3371

重要中國瓷器及工藝精品

Hong Kong, HKCEC Grand Hall|2014年11月26日

拍品3313|清 粉彩缠枝莲花瓶

VARIOUS PROPERTIES

A FAMILLE ROSE VASE

QING DYNASTY, 18TH CENTURY

成交總額 HKD 2,200,000

估價 HKD 1,200,000 – HKD 2,500,000

A FAMILLE ROSE VASE

QING DYNASTY, 18TH CENTURY

The vase is colourfully enamelled with four pairs of fish tied with ribbons that suspend chimes, all reserved on a lively ground of dense scrolling lotus. The foot is surrounded by a stiff leaf band above a further band of flower scrolls and gilt classic scroll. The interior and base are enamelled turquoise.

12 5/8 in. (32 cm.) high, box

参考:民国 斗彩缠枝花蒜头瓶编号: 2030

拍品信息

成交价–

类别瓷器

作者 暂无

年代暂无

规格

高34.8cm;

口径4.5cm;

底径11cm

预展时间2008-10-23 09:00–2008-10-25 20:00

预展地点北京京瑞饭店二层宴会厅,三层阳光大厅(北京市朝阳区东三环南路17号)

拍卖公司北京中嘉国际拍卖有限公司

拍卖时间2008-10-26

拍卖会名称2008秋季艺术品拍卖会

拍卖会专场瓷器 玉器 书画 杂项 家俱专场

拍卖地点北京京瑞饭店十八层会议大厅

拍品描述

瓶蒜头口,束颈饰两道弦纹,溜肩鼓腹,圈足。通体斗彩绘画缠枝莲花,花色多样,线条顺畅,描画精细,填彩准确,足部青花绘回纹一周底落青花楷书“大清雍正年籹”双圈款。 高34.8 cm口径4.5 cm底径11 cm A DOUCAI VASE WITH DESIGN OF FLOWERS Republic of China H34.8 cmD(top)4.5 cmD(bottom)11 cm

参考:

拍卖公司 红太阳国际拍卖有限公司

拍卖会 2010年秋季拍卖会

拍卖时间 2010-12-25

0227 清 斗彩缠枝莲纹蒜头瓶

拍品信息

作者 —

尺寸 高27.5cm

作品分类 陶瓷 清代斗彩瓷器

创作年代 清

估价 RMB 780,000-980,000

成交价 流拍

专场 瓷器

说明 质地:瓷

备注:“大清乾隆年制”

说明:此件蒜头瓶,造型优美漂亮,斗彩绘制有缠枝莲纹,纹样精美,描绘线条流畅,彩色艳丽柔和,胎体洁白细腻,保存完好,十分难得。

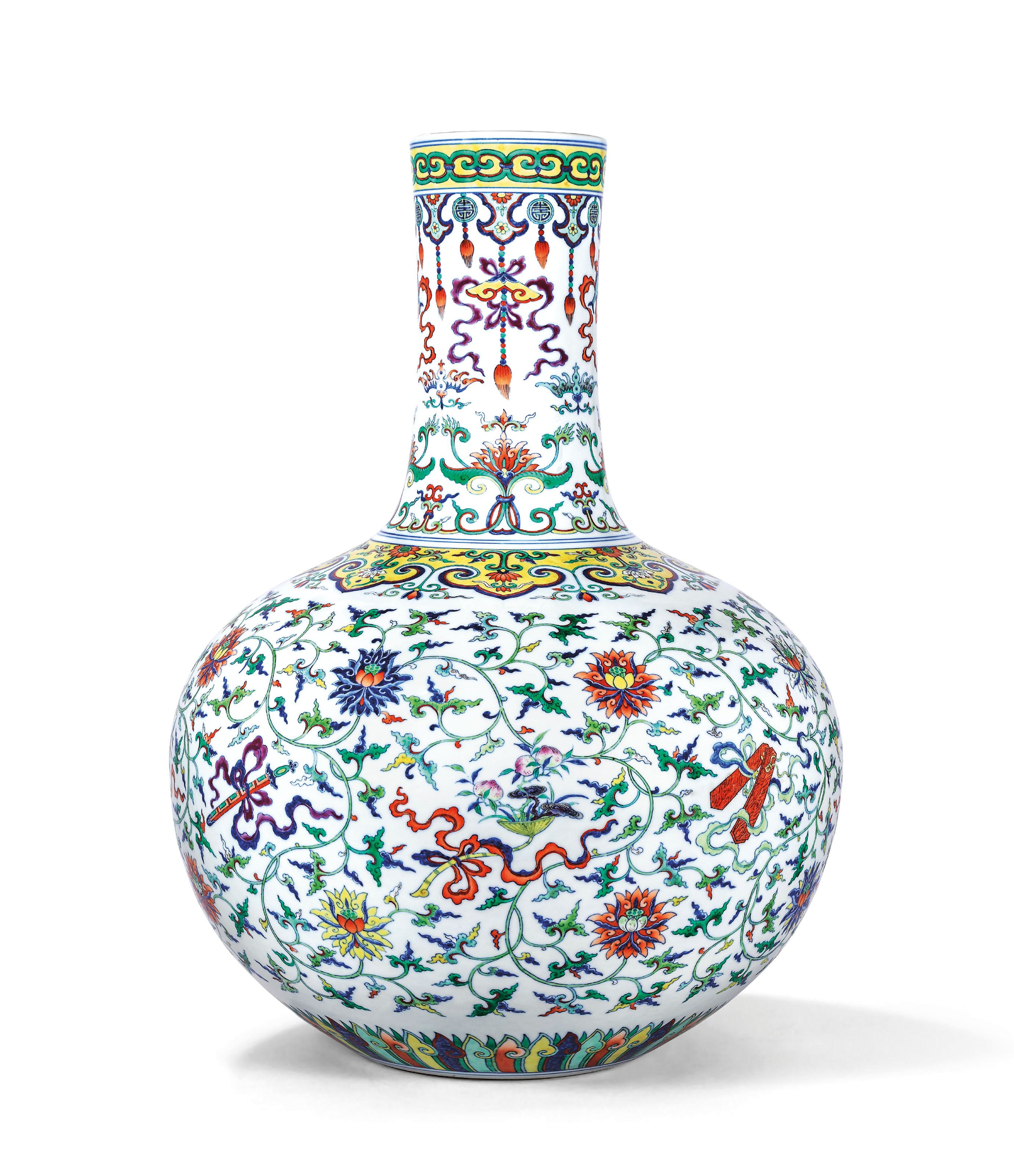

参考:LOT 8888

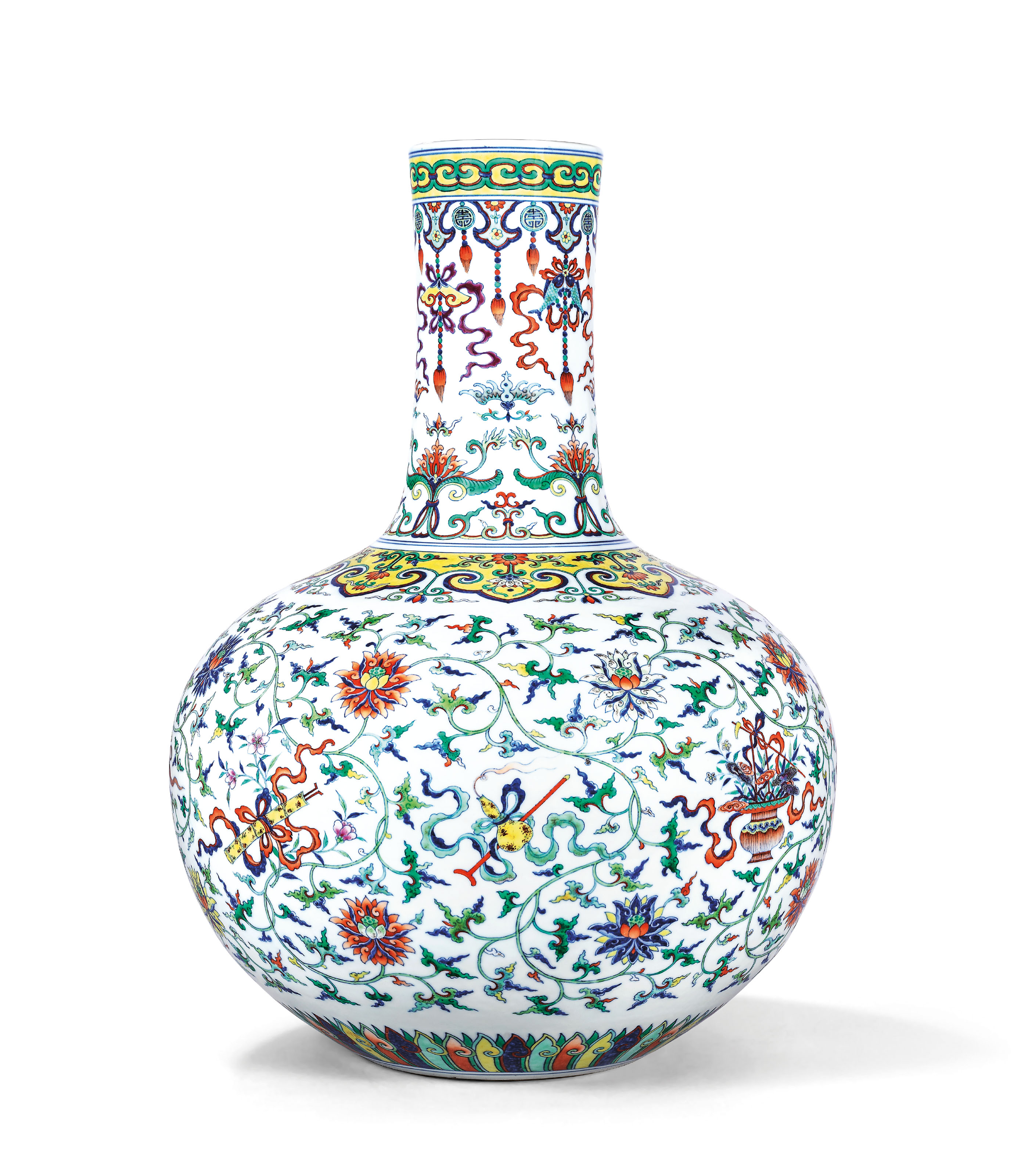

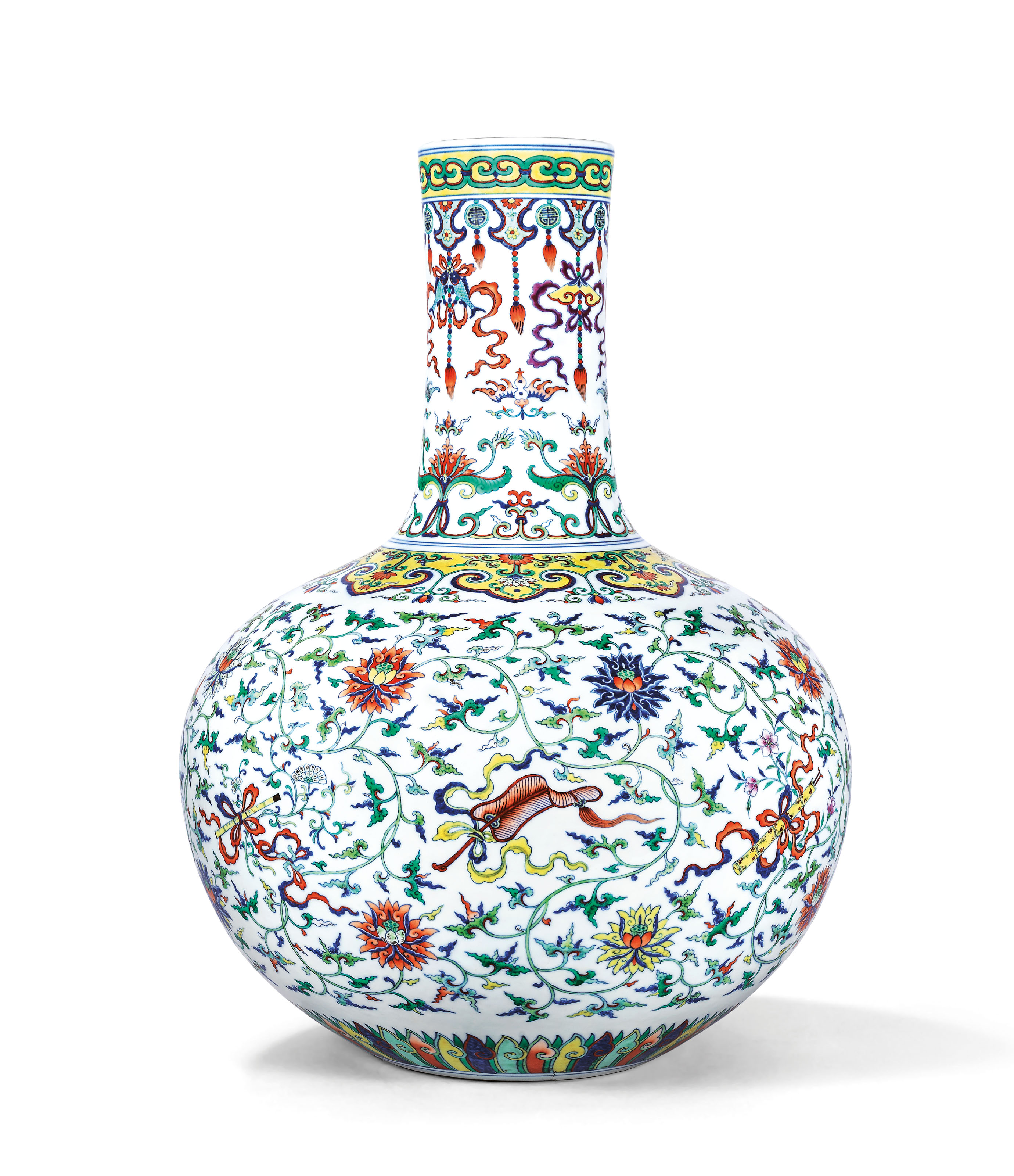

A FINE MAGNIFICENT AND EXTREMELY RARE DOUCAI AND FAMILLE ROSE ‘ANBAXIAN’ VASE, TIANQIUPING

QIANLONG SIX-CHARACTER SEAL MARK IN UNDERGLAZE BLUE AND OF THE PERIOD (1736-1795)

Price realised

HKD 130,600,000

Estimate

HKD 70,000,000 – HKD 90,000,000

A FINE MAGNIFICENT AND EXTREMELY RARE DOUCAI AND FAMILLE ROSE ‘ANBAXIAN’ VASE, TIANQIUPING

QIANLONG SIX-CHARACTER SEAL MARK IN UNDERGLAZE BLUE AND OF THE PERIOD (1736-1795)

The magnificent vase is superbly potted with a globular body surmounted by a columnar neck, delicately enamelled in the doucai and famille rose palettes, on the body with the anbaxian, ‘Eight Daoist Emblems’, each tied with flowing ribbons, amid leafy scroll issuing lotus blossoms in two rows, all between lappets at the foot and a band of cloud-shaped collar at the shoulder. The neck is enamelled with four lotus blossoms, beneath pendent double-fish and musical chimes.

21 1/4 in. (53.9 cm.) high

Provenance

George Hathaway Taber (1859-1940) Collection, prior to 1925, and thence by descent within the family

Mrs. Francis Keally (nee Mildred Taber, 1891-1975) Collection

Philbrook Museum of Art, Tulsa, Oklahoma, gift of Mrs. Francis Keally,

accessioned in 1960

Pre-Lot Text

PROPERTY FROM PHILBROOK MUSEUM OF ART SOLD TO BENEFIT THE ACQUISITIONS ENDOWMENT

The current vase is a magnificent example of imperial Qianlong porcelain. The name of this shape of vase in Chinese is tianqiuping‘heavenly globe vase’, and it is significant that in Chinese iconography the earth is represented by a square, while heaven is represented by a circle. Hence, the large globular body of such vases provides an ideal reference to heaven. This vase is a particularly large and impressive specimen of the tianqiuping shape. The vessel is extremely well-potted and the generous globe of the body has retained its form even after firing, while some other examples can be seen to have sunk slightly under their own weight. The neck is in ideal proportion to the body, and has also remained in perfect alignment. The fact that this large vessel has fired so perfectly is a testament to the great skill of the potter, who has not only thrown it absolutely evenly – so that it did not distort in the kiln – but has perfectly judged the thickness of clay and precise junction of the neck to prevent the latter from sinking into the body during firing.

Although the tianqiuping shape appears in Chinese porcelains as early as the 15th century of the Ming dynasty in China, the 15th century examples have a shorter neck in proportion to the body than the 18th century vases. This can be seen on the early 15th century blue and white tianqiuping in the collection of the Palace Museum Beijing, illustrated in Blue and White Porcelain with Underglaze Red (I), The Complete Collection of Treasures of the Palace Museum, vol. 34, Hong Kong, 2000, pp. 90-95, nos. 87-89 (fig. 1). The tianqiuping shape really came to prominence in the 18th century on imperial porcelains commissioned by emperors who were unconcerned by the cost of producing such extravagant vessels. A number of tianqiuping were made in the Yongzheng reign (1723-35) – primarily with underglaze blue or overglaze famille rose decoration. An example of the latter, decorated with blossoming chrysanthemums, and somewhat smaller than the current vase, is in the collection of the Tokyo National Museum (illustrated in Oriental Ceramics, The World’s Great Collections, vol. 1, Tokyo, 1976, col. pl. 80. (fig. 2)). Two Yongzheng tianqiuping of similar size to the current vase, but decorated in underglaze blue, from the Qing court collection of Palace Museum, Beijing, are illustrated in Blue and White Porcelain with Underglaze Red (III), The Complete Collection of Treasures of the Palace Museum, vol. 36, Hong Kong, 2000, pp. 96-7, nos. 82 and 83.

It is very rare to find a vase of this massive size with doucai decoration. This was a difficult and expensive decorative technique. First, the fine underglaze cobalt blue outlines were painted onto the porous unfired body. As the cobalt immediately soaked into the unfired clay, no mistakes could be rectified. The vessel was then glazed and fired. After the glazed piece had cooled, the overglaze enamels were carefully applied inside the underglaze blue outlines and the piece was fired again at a lower temperature. As each firing would have resulted in some failures, and large vessels tended to be more susceptible to warping and splitting, it would have been an expensive undertaking to create large doucai vessels which met imperial high standards. It is telling that even the Palace Museum in Beijing appears to have published only one Qianlong doucai vase (decorated with tribute bearers) which is as tall as the current vase(illustrated in Porcelains in Polychrome and Contrasting Colours, The Complete Collection of Treasures of the Palace Museum, vol. 38,

Hong Kong, 1999, p. 274, no. 251)(fig. 3). Even the famous Qianlong doucai dragon moon flask in the Palace Museum (illustrated by E.S. Rawski and J. Rawson (eds.) in China – The Three Emperors 1662-1795, London, 2005, pp. 294-5, no. 217) is 6 cms. smaller than the current vase, while the large Qianlong doucai charger, decorated with the Eight Buddhist Emblems, from the imperial collection in the Nanjing Museum (illustrated in Qing Imperial Porcelain of the Kangxi, Yongzheng and Qianlong Reigns, Nanjing, 1995, no. 104) is 5 cm. smaller. The famous Qianlong doucai flask with a design of a farmer ploughing his fields (inspired by the 1696 Yuzhi Gengzhi tu, Imperially commissioned Pictures of Tilling and Weaving) in the collection of the Tianjin Museum of Art (illustrated in Zhongguo wenwu jinghua daquan – Taoci juan, Taipei, 1993, p. 442, no. 936) is of comparable size to the current vase.

A Qianlong tianqiuping with doucai decoration, but of smaller size (H: 42 cm.) is in the collection of the Matsuoka Museum of Art in Japan (illustrated in Masterpieces of Oriental Ceramics from Matsuoka Museum of Art, Japan, 1997, p. 43, no. 33). A Qianlong imperial tianqiuping decorated in underglaze red and blue with some celadon areas, and another decorated in underglaze blue, and a further Qianlong tianqiuping with monochrome blue glaze, of slightly larger size to the current vase, are in the collection of the Nanjing Museum (illustrated in in Qing Imperial Porcelain of the Kangxi, Yongxzheng and Qianlong Reigns, Nanjing, 1995, nos. 80, 77 and 66, respectively).

It seems likely that the current vase was made at the imperial kilns early in the Qianlong reign. There are several aspects of the decoration that suggest this dating. Perhaps most telling is the delicacy and use of colour seen in the doucai decoration, which is akin to that of the Yongzheng reign. The underglaze blue outlines are both paler and narrower than those found on the majority of Qianlong doucai vessels, while the blue washes

are softer in appearance. The overglaze enamel colours are also applied with considerable restraint – highlighting certain aspects of the design without producing an overall gaudiness. The use of colours on the current vase may perhaps be compared with that of the Yongzheng doucai meiping in the collection of the Palace Museum, Beijing, which is illustrated in Porcelains in Polychrome and Contrasting Colours, The Complete Collection of Treasures of the Palace Museum, vol. 38, Hong Kong, 1999, p. 245, no. 225. (fig. 4) There are also small details, such as the style of the petal band which encircles the foot of the current vase. This is relatively rare in the Qianlong reign, but can be found more often on Yongzheng porcelains, such as the enamelled bowl illustrated in Porcelains in Polychrome and Contrasting Colours, op. cit., p. 171, no. 157.

An early Qianlong date is also suggested by the seal-script reign mark in underglaze blue on the base of the vase. Professor Peter Lam has conducted detailed research into the form of reign marks during the Qianlong reign, and the reign mark on the current vase accords most closely with the style that he denotes ‘type 5’. (see Peter Y.K. Lam, ‘Towards a Dating Framework for Qianlong Imperial Porcelain’, Transactions of the Oriental Ceramic Society, vol. 74, 2009-2010, p. 23). Interestingly, Lam describes this mark as ‘…similar to the standard squarish seal mark of Yongzheng …, but the brushstrokes are more angular’. Lam estimates that this style of seal mark was in use from approximately the 7th to the 35th year of the Qianlong Emperor’s 60-year reign. This would mean that the current vase was made during the tenure of the most revered of all the supervisors of the Qing Imperial kilns, Tang Ying (1682- 1756), under whose auspices some of the finest imperial porcelains were made.

In addition, an early Qianlong date is suggested by a note in the palace records which states that on the twenty-fifth day of sixth month of Qianlong third year (1738): [a model of] ‘a large wucai tianqiu zun decorated with the Eight Daoist Emblems was presented …[The Emperor decreed] Manufacture accordingly, and return the original porcelain model to the porcelain storeroom when it is done’. Although the vessel mentioned in the records is described as wucai, rather than doucai, it may nevertheless refer to the same type of vessel as the current vase, and at the very least indicates that the Qianlong Emperor commissioned the Eight Daoist Emblems to be applied to tianqiuping at this early date.

Although the vessel mentioned in the records is described as wucai, rather than doucai, it may nevertheless refer to the same type of vessel as the current vase, and at the very least indicates that the Qianlong Emperor commissioned the Eight Daoist Emblems to be applied to tianqiuping at this early date.

The choice of decorative motifs on the current vase are rare on Qianlong doucai porcelains. The body of the vase is decorated with a delicate lotus scroll with multicoloured blossoms and punctuated with the Eight Daoist Emblems tied alternately with red and blue ribbons. The Eight Daoist Emblems are the attributes of the Eight Daoist Immortals. The fan belongs to Han Zhongli, the gourd (which contains magic potions) and iron crutch belongs to Li Tieguai, the bamboo drum and metal drum sticks belong to Zhang Guolao, a lotus or bamboo sieve belong to He Xiangu – the only female member of the group, who is regarded as the patron saint of housewives, a basket of flowers or peaches belong to Lan Caihe, the sword and fly whisk belong to Lu Dongbin, the pair of castanets belong Cao Guojiu, and the flute belongs to Han Xiangzi. While these attributes were seen accompanying the Eight Immortals from the Yuan dynasty (1279-1368), it was only in the Qing dynasty that the attributes alone became a popular motif, imbued with the same auspicious wishes as the immortals to whom they belonged. It seems that the Daoist Emblems’ first appearance alone on porcelains was in the Yongzheng reign. While the Qianlong Emperor, like his father and grandfather, was a devout Buddhist, the inclusion of Daoist symbols on an imperial vase would have been entirely

appropriate in view of their auspicious message.

On the neck suspended, beribboned, qing chiming stones alternate with suspended, beribboned, twin fish, with downward facing bats below. The chiming stone, also known as a lithophone, and called a qing in Chinese, is generally L-shaped, like a carpenter’s square and can be traced back to the Neolithic period. It is suspended by its apex and played using a mallet. During the Qing dynasty sets of twelve such chiming stones were made of jade for the palace where they were suspended on racks and were played on ceremonial occasions. Chiming stones are often included in porcelain decoration because qing chiming stone is a rebus

for qing meaning to celebrate. The twin fish (shuang yu) are usually included in the Eight Buddhist Emblems, but are also auspicious on their own, symbolising marital bliss, many children and abundant good luck. The bats on the neck of the vessel also provide an auspicious wish, since in the Chinese arts bats (fu)

provide a rebus for happiness (fu). It is no accident that the bats on the vase are shown upside-down. The Chinese word for upside-down (dao) has the same sound as the word for arrived (dao). Therefore, an upside-down bat indicates the arrival of happiness. The Eight Daoist Emblems combined with a suspended

qing chiming stone can be seen on a Qianlong ruby-ground famille rose vase in the Palace Museum, Beijing (illustrated in Porcelains with Cloisonne Enamel Decoration and Famille Rose Decoration, The

Complete Collection of Treasures of the Palace Museum vol. 39, Hong Kong, 1999, p. 145, no. 127. A combination of twin fish, qing chiming stone and bats can be seen on the Qianlong doucai vase in the Palace Museum with scenes of tribute bearers, mentioned above. The exceptional quality, monumental size, and imposing presence of the current tianqiuping, as well as its fine and auspicious decoration, would have rendered it suitable for prominent display in one of the halls of the Qing palace.

This rare vase has a prestigious provenance, having been donated to the Philbrook Museum of Art in Tulsa, Oklahoma in 1960 by Mrs. Francis Keally. The vase was inherited by Mrs. Keally from her father George Hathaway Taber Jr. (1859-1940) who was a prolific collector of Chinese ceramics and jades with a discerning eye for quality and an unusually good understanding of what was appreciated by Chinese connoisseurs. The son of Capt. George H. Taber (1808-1901), who rose from a humble background to

become a prominent member of the community filling a number of important offices including serving as President of Fairhaven Bank, George Taber Jr. made his mark as an oil executive, and ultimately board member, with the Gulf Oil Company. A selftaught engineer, he was instrumental in developing important

advances in oil refining techniques. Believed to have been inspired by a relative who travelled to China and brought back not only fascinating tales but also beautiful objects, George Taber Jr. built up an extraordinary collection which was loaned or gifted to a number of museums. Upon his death in 1940, the collection was

divided between his descendants and part of it was sold at the Parke Bernet Galleries, New York, 7-8 March 1946. The Philbrook Asian art collection is particularly strong in Japanese paintings from the Edo period (1603-1868), which came from the Shin’enkan collection of Oklahoma oil magnate, Joe D. Price. A further

major gift, in this case of Southeast Asian ceramics, came from the Gillert Family, while the Taber Family donated Chinese ceramics and carvings. The current superb Qianlong vase, given by Taber’s daughter, Mrs. Francis Keally, has been an esteemed signature piece in the museum’s Asian art collection.

![[临渊阁]天地一家春](https://www.antiquekeeper.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/BW-Erping-1a-17-6-1.jpg)