Description

明 哥釉瓜棱紋水洗 菊花紋水丞

参考:佳士得

15 3月 2015| 現場拍賣 3720

重要中國瓷器及工藝精品

拍品 3243南宋/元 哥窯水丞

AN EXQUISITE AND EXCEPTIONALLY RARE GEYAO WATER POT

PROPERTY FROM A DISTINGUISHED PRIVATE COLLECTION

SOUTHERN SONG-YUAN DYNASTY (1127-1368)

成交價USD 1,085,000

估價USD 1,000,000 – USD 1,500,000

來源

Christie’s Hong Kong, 1 November 2004, lot 802.

出版

Christie’s 20 Years in Hong Kong, 1986 – 2006, Chinese Ceramics and Works of Art Highlights, p. 31.

狀況報告

– In good condition overall.

– The lustrous glaze of an even tone.

– There is a little speckling in the glaze around the mouth.

– There is a minor minute bruise to the glaze on one side, and a minute burst glaze bubble, both possibly original to the manufacture.

– There are two slight indentations to the lower body on either side near the foot which are inherent to manufacture.

拍品專文

This water pot has an exceptionally well-potted spherical form. Small compressed globular water pots with celadon glazes were made in Zhejiang province as early as the Southern Dynasties period (AD 420-589). One such vessel, excavated from a 5th century tomb in Yongjia county and now in the Wenzhou Museum, is illustrated in Complete Collection of Ceramic Art Unearthed in China, vol. 9, Zhejiang, Beijing, 2008, p. 87. Similar compressed globular water pots, with or without three small feet, were also made at the Ou kilns and the Yue ware kilns in the Tang dynasty. Examples from the Wenzhou Museum and the Cixi Museum are illustrated ibid, pp. 126 and 127 respectively. However, in the Five Dynasties period well-potted spherical water pots can be found amongst vessels from prestigious kilns which found favour with the imperial court. A mise celadon water pot of this spherical form, and of very similar size to the current Ge ware vessel, was excavated in Lin’an county in 1996 from the Kangling Mausoleum (dated AD 939), illustrated ibid., p. 143. A fine 10th-century spherical white-glazed water pot with incised lotus decoration, slightly smaller than the current Ge ware vessel, is in the collection of the Tokyo National Museum. This white water pot, which is illustrated in Sekai toji zenshu, vol. 11, Sui Tang, Tokyo, 1976, pp. 115-6, pls. 92-3, is inscribed on the base with the characters xin guan (new official). Although the Tokyo water pot has no neck or raised mouth rim, a small Ding ware spherical water pot (7.5 cm high) with a very short neck was excavated in 1969 from the foundations of the Jingzhongyuan Temple pagoda, dated AD 995, illustrated by the Idemitsu Museum of Arts in Treasures from the Underground Palaces – Excavated Treasures from Northern Song Pagodas, Dingzhou, Hebei Province, China, Tokyo, 1997, no. 90. A larger spherical Ding ware water pot with longer neck and thickened rim, also from Jingzhongyuan Temple pagoda, is illustrated by Liu Tao in Song Liao Jin jinian ciqi, Beijing, 2004, p. 5, fig. 1-29. Thus, by the early Northern Song dynasty, late 10th century, the spherical form for small water pots was already established as desirable amongst the Chinese elite.

A Guan-type water pot of similar size to the current vessel, with a spherical body, but standing on three short, splayed legs, is illustrated in Mayuyama Seventy Years, vol. 1, Tokyo, 1976, p. 161, no. 467. A Guan or Ge ware spherical water pot, also of similar size to the current vessel, was sold by Christie’s Hong Kong on 13 January 1987, lot 570. A water pot with Guan-type glaze, of slightly smaller size compared to the current vessel, and of compressed globular form, is illustrated in Chinese Ceramics, Song and Yuan Dynasty, Taipei, 1988, p. 515. A slightly larger 13th century spherical celadon-glazed water pot from the Longquan kilns, with floral surface decoration, is in the collection of Sir Percival David (illustrated in Illustrated Catalogue of Celadon Wares in the Percival David Foundation of Chinese Art, revised edition, 1997, pp. 29-30, no. 232), and was exhibited in Arts de la Chine Ancienne at the Musée de l’Orangerie, Paris, in 1937, exhibit no. 447. Nevertheless, few examples of similar vessels from any of the classic kilns of the 10th-13th century have survived into the present day.

Since the Ming dynasty, Ge wares have been regarded as one of the ‘Five Great Wares of the Song Dynasty’, along with Ru ware, Ding ware, Jun ware, and Guan ware. These wares remain the most revered wares of the Song dynasty (AD 960-1279), a period which Chinese connoisseurs have traditionally admired above all others for the refined beauty of its ceramics – typified by vessels with elegant forms, enhanced with subtly colored monochrome glazes. A variety of such wares were appreciated by members of the Song elite and the imperial court, as well as by later collectors, but texts tell us that these five types were held in particular esteem. Ge ware and Guan ware have been the subjects of extensive research by Chinese scholars and those from other countries in recent years, and they continue to be at the forefront of interest amongst scholars and collectors alike. Both Guan ware and Ge ware are characterized by subtly-colored glazes which were deliberately crackled to achieve a fine network of lines over the surface of the vessel. One of the reasons that these crackle lines were admired was that they were reminiscent of the fissures in jade, the most prized of all natural materials.

The high regard in which such pieces were held by the great Qing dynasty imperial collector, the Qianlong Emperor (1736-1795), for example, is demonstrated by the fact that Ge ware dishes appear in several informal portraits of the emperor. One such portrait is the famous painting entitled ‘One or Two?’, of which there are three versions in the Palace Museum, Beijing. One of these is illustrated in the catalogue of the exhibition, The Qianlong Emperor – Treasures from the Forbidden City, at the National Museums of Scotland, Edinburgh, 2002, p. 112, no. 59. The Qianlong emperor is shown seated on a day-bed in front of a screen on which is hung a portrait of himself, and surrounded by precious objects from his famous collection of antiques. One of these is a small crackled dish, which appears to be Ge ware. The admiration of the Qianlong Emperor for Ge wares can also be seen in the inscriptions that he applied to pieces in his collection. A recent exhibition at the National Palace Museum, Taipei, included eight Ge wares bearing Qianlong inscriptions (illustrated in Obtaining Refined Enjoyment: The Qianlong Emperor’s Taste in Ceramics, Taipei, 2012, nos. 35-7, 40-1, 43, 45, and 93). The same exhibition displayed a page from Qianlong’s hand-painted album Precious Ceramics of Assembled Beauty, which showed a Ge ware dish along with a discussion of the piece and various imperial seals (illustrated ibid., p. 203).

The Palace Museum, Beijing, has in its collection a censer, identified as Ge ware, which bears a Qianlong inscription (illustrated in The Complete Collection of Treasures of the Palace Museum – 33 – Porcelain of the Song Dynasty (II), Hong Kong, 1996, no. 51). The popularity of Ge and Ge-type wares at the courts of the Qing emperors is emphasised by the number of such pieces from the Qing Court Collection which are preserved in the Palace Museum, Beijing. Some 40 examples are published in Porcelain of the Song Dynasty (II), op. cit.

Examination of the Qianlong inscriptions highlights the subject on which there has been considerable debate among scholars and connoisseurs – the difficulty of determining whether a particular piece should be described as Guan ware or Ge ware. Certainly to judge from the Qianlong emperor’s inscriptions, he was inconsistent in his attributions. Traditionally it is said that Ge ware acquired its name from the Chinese term gege, meaning elder brother, since it was believed to have been made by the elder of the two Zhang brothers. Distinguishing between Ge and Guan ware is not greatly aided by the historical texts, which merely say that they looked similar to one another. A symposium held by the Shanghai Museum in October 1992 brought together all the leading Song ceramic scholars from China and abroad to discuss Ge ware and the ways to distinguish it from Guan ware. However, the debate regarding exact period of production and kiln site still rages. In light of the excavations carried out at the Xiuneisi kiln at Laohudong, some Chinese archaeologists now suggest that, like Guan ware, these beautiful and refined Ge wares may have been made at kilns just outside the walls of the Southern Song palace at Hangzhou, while others suggest that they may have been made at kilns nearer to the centre of Longquan production. Undoubtedly Ge wares, like the current water pot, display all the qualities that might be expected of vessels intended for imperial appreciation.

Rosemary Scott

International Academic Director, Asian Art

参考:佳士得拍賣 13755

開元大觀

Convention Hall|2016年6月1日

拍品3126

南宋 官窯十棱葵瓣洗

SOUTHERN SONG DYNASTY (1127-1279)

南宋 官窯十棱葵瓣洗

南宋 官窯十棱葵瓣洗

南宋 官窯十棱葵瓣洗

成交總額

HKD 38,200,000

估價

HKD 30,000,000 – HKD 40,000,000

南宋 官窯十棱葵瓣洗

洗呈十瓣葵口形,侈口,淺壁,底略凹,有支釘痕跡六枚。通體滿施青釉,釉色勻潤,釉表開細密紋片,口緣釉薄處呈褐色。

4 3/4 in. (12 cm.) wide

來源

Harry Garner爵士及夫人珍藏,貝肯翰姆,英國

賽穆旼(Mortimer D. Sackler)醫生珍藏

文獻及展覽

展覽

東方陶瓷學會,《Ju and Kuan Wares》,倫敦,1952年11月12日至12月13日,圖錄圖版67號

總督宮,威尼斯,《Mostra d’arte Cinese》,1954年,圖錄圖版460號

拍品專文

南宋 官窯葵瓣洗

蘇玫瑰

亞洲藝術部資深學術顧問

是次拍賣的官窯洗精美絕倫,充份體現了南宋御瓷的輝煌成就。此外,這批特為南宋宮廷燒造的官窯佳瓷,亦承襲了北宋宮廷的審美趣味。它們深受歷代藏家推崇,對後世的御瓷燒造影響深遠,時至清代仍方興未艾。

在陶瓷史上,只要論及北宋美學,影響力之大首推宋徽宗(1100-1126年在位)。誠然,徽宗最為人津津樂道的並非其為君之道,反而是他的收藏、藝術和美學造詣。他曾命人為其古董珍藏刊印圖錄,更諭令製成各式宮室廟宇用器,凡此種種,堪稱中國藝術史上的豐功偉績。若要探討官窯瓷器,徽宗與南宋宮廷藝術之間的淵源亦不容勿視,因為徽宗朝中用器的典雅風格 (例如為其燒造的汝窯御瓷),正是南宋官窯御瓷的主要參照對象。

由於金軍大舉進犯,徽宗於公元1126年1月遜位,其子趙桓登基為欽宗。欽宗於1127年1月向女真求和,同年3月被廢。1127年5月,徽欽二宗被擄至東北金都。此時華北雖然失守,但宋代仍氣數未盡。1126年,徽宗第九子趙構曾出使華北金營議和,途中經朝臣多番勸諫,終起兵抗金。他避過金軍的重重追捕,亦逃脫了其父兄及數千宗室及官兵被押解至北方的命運。欽宗於1127年3月被廢,其弟趙構於同年6月在河南應天府 (今商丘) 稱帝,是為宋高宗。

由於金國節節進逼,宋高宗退守浙江東南的臨安 (今杭州),並於1129年在當地設置「行宮」。是次南遷美其名曰「渡江」,後世學者則視之為北宋與南宋的分水嶺。紹興八年 (1138年),宋高宗定都臨安,稱之為「行都」,可見宋室仍懷着有朝一日光復華北、重回開封舊都的願望。臨安皇城建於鳳凰山北麓山腳處。

宋室南渡之後偏安杭州,此時北方窯口的製品不再唾手可得,而他們南下時亦無法攜帶太多器物。此外,金軍1127年北歸途中,亦掠走了不計其數的宮廷奇珍。早年為宋徽宗燒造的汝窯名瓷雖馳名海內,但在南宋宮廷定然供不應求。更重要的是,陶瓷器物雖然不是北宋宮廷禮器的主流,但由於青銅器不敷應用,這意味着南宋朝廷可能要用陶瓷禮器取而代之。為此,朝廷亟待物色新的窯口,燒造宮中祭祀和常用精瓷。尤須一提的是,官窯遺址的出土文物中也有陶瓷禮器。這固然可歸功於徽宗好古博雅的遺風,以及他為青銅文物珍藏(大多數被金軍在開封洗劫一空並帶回北方) 所出版的圖譜,但部份精製瓷觚、瓷罍及瓷簋,很可能是南宋宮室為替代青銅祭器而燒造的代用品。

起初,南宋朝廷應屬意越窯燒製官瓷,這是因為浙江越窯歷史悠久,北宋初年其製成品在宮中風行一時,所以此舉堪稱意料中事。奈何最後的成果未如理想,故杭州官窯終於在1144年正式成立。史籍曾提及兩個官窯,一處為郊壇下官窯,考古學家早於1930年代已確定其窯址位於杭州市郊烏龜山。其後,該址曾多次進行發掘工作,其中又以1980年代的檢測和發掘最曠日持久、鉅細無遺。但除此之外,文獻中還提到一個年代更早的窯口,即修內司官窯,但其窯址要到1996年始有定論。雖然如此,大家一直視之為極品官瓷的出處。關於修內司窯,最膾炙人口的記述來自陶宗儀 (1316-1403年)的兩本著作,但二者內容大同小異:其一是陶氏編修及身後出版的《說郛》,書中引述了南宋作家顧文薦《負暄雜錄》的記載;其二是《輟耕錄》,其引文來自南宋葉寘著作《坦齋筆衡》:「中興渡江,有邵成章提舉後苑,號邵局,襲故京遺制,置窯於修內司,造青器,名內窯,澄泥為花,極其精製,釉色瑩澈,為世所珍,後郊壇下別立新窯,比舊窯大不侔矣。」中國的考古學家現已在老虎洞找到了修內司窯遺址,該處距鳳凰山南宋皇城北面城墻不足一百米。上述關於修內司窯成立的記載,後世文獻多有提及,但據現

代學者沙孟海考證,內侍邵成章雖於徽宗 (1101-25年) 朝中任官,但被罷免後流放至南雄州,自此不曾還朝,詳見沙孟海於《考古與文物》1985年6號刊發表的<南宋官窯修內司窯址問題的商榷>。由此推論,邵成章不可能是開辦南宋官窯的功臣。但一直以來,學者皆假定修內司窯的成立早於郊壇下窯,而且其作品確實勝於後者。我們若比較一下館藏文物,以及老虎洞與郊壇下窯的出土標本,似乎亦與此說相符。潛說友曾奉南宋度宗 (1265-74年) 之命編撰《咸淳臨安志》,書中載有一幅杭州鳳凰山南宋皇城圖。圖中近宮墻東北面,有兩處書「修內司營」四字,修內司以「營」為編制,亦軍亦工。圖中所示方位,亦與老虎洞位置及文獻中記述的修內司窯址大致脗合。1996至2002年期間,老虎洞出土了五個地層,最上層為近代遺存,第二層為元代遺存,第三及第四層的斷代為南宋,第五層為北宋。至於兩個南宋地層的出土陶瓷,皆符合文獻中關於修內司官窯器物的描述。

顧文薦在《負暄雜錄》中指出,出自修內司窯的官瓷除了做工精妙,部份還有「蟹爪紋」和「紫口鐵足」。就立燒而成的器物,窯燒前必須擦掉器足的釉料,以致含鐵豐富的深色胎土外露,此乃「鐵足」;另外,口沿因流釉而釉層偏薄,胎土隱約外露,故名「紫口」。《負暄雜錄》還提到,修內司窯的精製陶瓷與汝瓷如出一轍,詳見顧文薦《負暄雜錄》卷十八 (涵芬樓本)。曹昭1388年著成《格古要論》,書中對官窯瓷器亦持相同的看法:「宋修內司燒者,土脈細潤,色青帶粉紅,濃淡不一,有蟹爪紋,紫口鐵足,色好者類汝窯。」就此,可參閱大維德爵士譯註本《Chinese Connoisseurship: The Ko Ku Yao Lun, The Essential Criteria of Antiquities》,書內附中文摹本 (倫敦:1971)。上述特徵 (包括北宋汝瓷的傳承),既見諸於老虎洞窯址南宋地層出土的陶瓷,亦適用於是次拍賣的官窯洗。

南宋和元代官窯似乎曾燒造多款近似本拍品的棱口洗,它們或開六棱或八棱,或像本拍品呈十棱,多者甚至有十二棱。這類作品的器底均施滿釉,並用支釘燒造。老虎洞修內司窯曾出土數件近似例,其中一例為八棱洗,圖見《杭州老虎洞窯址瓷器精選》編號123 (北京:2002)。北京故宮博物院藏兩例十棱官窯洗,發表於《故宮博物院藏文物珍品大系33:兩宋瓷器 (下)》頁22編號17 (圖一) 及頁25編號20 (圖二) (香港:1996)。巴婁爵士伉儷亦珍藏一例十棱官窯洗,現已納入牛津大學艾希莫林博物館,它曾於1952年倫敦【Ju and Kuan Wares】展覽中亮相,圖見《東方陶瓷學會會刊》1951-1952年、1952-1953年27號刊圖版4編號72 (倫敦:1954)。另有一例十棱官窯洗為米禮肯伉儷舊藏,現為克里夫蘭美術館珍藏。這批十棱官窯洗俱用五根支釘窯燒而成,故足底釉面有五個相應的支釘痕。台灣國立故宮博物院亦珍藏一例十棱官窯洗,其底部有六個支釘痕,與本拍品如出一轍,圖見《故宮藏瓷:南宋官窯 (一)》下冊編號41 (香港:1962)。北京故宮珍藏一例近似六棱洗,圖見前述著作《故宮博物院藏文物珍品大系33:兩宋瓷器 (下)》頁24編號19。此外,大維德爵士曾珍藏三件八棱官窯洗,其登錄號為PDF 30、A53及A54。其中一例(PDF A53) 圖見《Song Ceramics – Objects of Admiration》頁96-7 (倫敦:2003)。此洗與PDF A54器底均有六個支釘痕,而較小的一例 (PDF 30) 則有五個支釘痕,圖見《Illustrated Catalogue of Ru, Guan, Jun, Guangdong and Yixing Wares in the Percival David Foundation of Chinese Art》(修訂本)頁29及頁60 (倫敦:1999)。傳世品中尚有二例八棱官窯洗,兩者器底均有六個支釘痕,圖見前述著作《故宮藏瓷:南宋官窯(一)》下冊編號39及40。巴婁爵士亦珍藏一例器型較小的十二棱瓷洗,現外借予牛津大學艾希莫林博物館展出。此洗是用五根支釘支燒而成。

是次拍賣的官窯洗佳妙無比,其釉色格外出眾,且紋片縱橫交織。它源自賈納爵士伉儷舊藏,曾亮相於東方陶瓷學會1952年舉辦的【Ju and Kuan Wares】展覽,圖見前述著作《東方陶瓷學會會刊》1951-1952年、1952-1953年27號刊編號67 (倫敦)。早於1954年,威尼斯為慶祝馬可.波羅七百年誕辰,曾舉行著名的【Mostra d’arte Cinese】展覽,本拍品也是展品之一,圖見展覽圖錄頁131編號460 (圖三)。

Harry Garner爵士(1891-1977)為傑出數學家、科學家、東洋藝術品收藏家及學者。生於英國,Garner爵士畢業於劍橋大學, 1916年加入皇家空軍,其後有份參與設計新型戰鬥機,並成為軍需部首席科學家。除了超然的科學成就,Garner爵士對東洋藝術品的研究亦作出重大貢獻。他的著作包括1954年出版的《Oriental Blue and White》、1962年出版的《Chinese and Japanese Cloisonné Enamels》及1979年出版的《Chinese Lacquer》,均是研究東洋藝術史的莘莘學子之啟蒙讀本。他同時建立其藝術品收藏,網羅瓷器、漆器及掐絲琺瑯等,大部分捐予大英博物館及維多利亞及阿伯特博物館,其餘則在其辭世後透過Bluett’s賣出。行內流傳Garner爵士曾以低至2.10英鎊的金額買得兩件汝窯盃托,並分別捐贈大英博物館及維多利亞及阿伯特博物館。

編製圖錄及詳情

拍品前備註

賽穆旼醫生藏品

賽穆旼 (Mortimer D. Sackler) 醫生、爵士,畢生以助人為樂,惠澤製藥研究領域,造褔各地機構學府,致力築構更具活力的世界,啟迪後人。

賽氏生於1916年,為移民家庭後裔,於美國及英國修讀醫學,及後偕同兄弟亞瑟 (Arthur) 及雷蒙 (Raymond) 在紐約創辦克里德莫爾心理學研究中心 (Creedmoor Institute for Psychologic Studies),遂成精神病理研究先驅,專為精神健康問題鑽研療法。

1952年,賽氏及雷蒙收購了當時在曼哈頓規模尚小的普渡菲特列公司 (Purdue Frederick Company)。往後數年,賽氏兄弟把業務發展成譽滿全球的普渡藥業 (Purdue Pharma) ,成為研究及發展方面的翹楚,推崇革新文化,令業界渙然一新。

倫敦《每日電訊報》曾經以「與眾不同的贊助人」形容賽氏,皆因「其策動的計劃儘管紛繁如鯽,他都每必全情投入。」賽氏與妻子杜麗莎.賽克勒 (Theresa Sackler) 女爵士及兄弟行善無間,為現代慈善事業記下不可或缺的一筆。受惠於其善款及指導的對象眾多,涵蓋倫敦國家美術館 (National Gallery of Art)、紐約大都會博物館 (Metropolitan Museum of Art)、紐約古根漢美術館 (Guggenheim Museum)、蛇形畫廊 (Serpentine Gallery)、泰特美術館 (Tate)、牛津及劍橋大學,以及多所同名醫學研究中心,遍及倫敦、格拉斯哥、布萊頓、愛丁堡、特拉維夫、紐約及波士頓。身為一位大慈善家,賽氏視野遼闊、學問淵博,從其涉足領域可見一斑:遠至西敏寺內亨利七世教堂 (Henry VII Chapel) 的修復,近及當代建築師約翰.包笙 (John Pawson) 為邱園(Kew Gardens)設計的石橋,反映賽氏古今同攬,為點亮人文光譜,任重而道遠。

賽氏一生屢得殊榮,先後於1997及1999年獲頒發法國榮譽軍團勳章軍官勳位 (Officer of the Legion of Honour) 及大英帝國最優秀勳章爵級司令勳位 (Honorary Knight Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire)。時至今日,賽氏尊名家喻户曉,已成慈善偉業及公益服務的代名詞。賽氏家族創下不朽傳奇,其灼灼光華,將隨繼往開來的善舉而永續流芳。

参考: 佳士得 拍賣 15488

中國瓷器及工藝精品

倫敦|2018年11月6日

拍品149

明 仿官釉八棱葵瓣洗

MING DYNASTY (1368-1644)

明 仿官釉八棱葵瓣洗

成交總額 GBP 16,250

估價 GBP 8,000 – GBP 12,000

明 仿官釉八棱葵瓣洗

5 ¾ in. (14.5 cm.) diam.

参考:佳士得 拍賣 3323

漱玉供菊 – 宋代藝術精品

香港|2014年5月28日

拍品3213|南宋 官窑菊纹盘

AN IMPORTANT AND EXTREMELY RARE GUAN CHRYSANTHEMUM-SHAPED DISH

SOUTHERN SONG DYNASTY (1127-1279)

成交總額

HKD 25,880,000

估價

AN IMPORTANT AND EXTREMELY RARE GUAN CHRYSANTHEMUM-SHAPED DISH

SOUTHERN SONG DYNASTY (1127-1279)

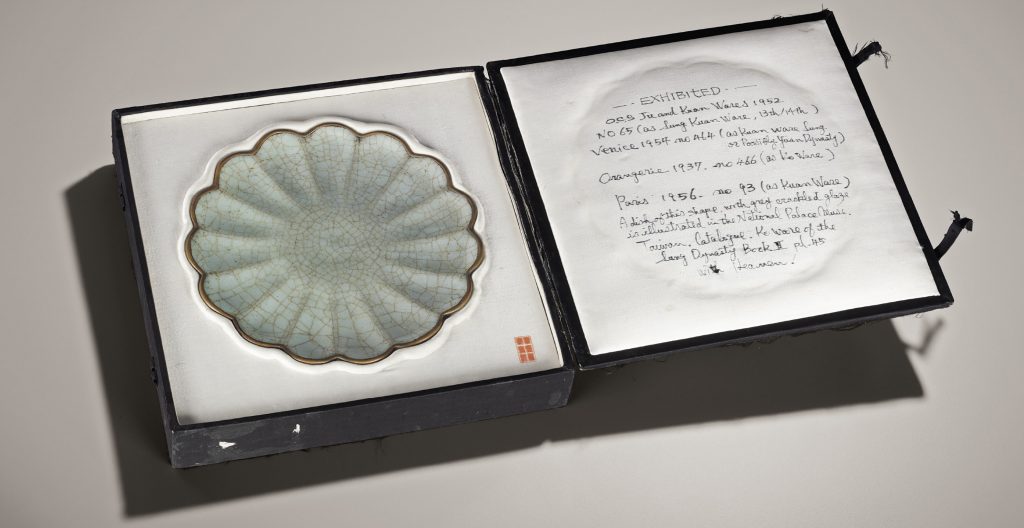

The dish is exquisitely potted with fifteen flutes flaring widely from the narrow circular foot and rising gently to the metal-bound rim, the interior similarly impressed with fifteen petals radiating from the slightly raised centre. The dish is covered overall with a thick pale greyish celadon glaze suffused with tiny bubbles and a dense network of russet crackle with the exception of the foot, exposing the purplish-brown body.

7 1/8 in. (18 cm.) wide, box

來源

Mrs. Alfred Clark Collection

Sold at Sotheby’s London, 25 March 1975, lot 100

Sakamoto Goro

Oriental Arts UK Ltd., London, purchased in 2002

文獻及展覽

展覽

Museé de l’Orangerie, Arts de la Chine Ancienne, Paris, 1937, Catalogue, no. 466

The Oriental Ceramic Society, Ju and Kuan Wares, London, 12 November to 13 December 1952, Catalogue, no. 65

Palazzo Ducale, Venice, Arte Cinese, 1954, Catalogue, no.464

Museé Cernuschi, L’Art de la Chine des Song, Paris, 1956, Catalogue, no. 93, pl. XVI

Osaka Municipal Art Museum, So Gen no Bijutsu, Osaka, 1978, Catalogue, no.

編製圖錄及詳情

拍賣現場通告

Please note that the provenance of this lot should read:

Mrs. Alfred Clark Collection

Sold at Sotheby’s London, 25 March 1975, lot 100

Sakamoto Goro

Oriental Arts UK Ltd., London, purchased in 2002

拍品前備註

Snow and Ice – Two Rare Song Dynasty Chrysanthemum Dishes

Rosemary Scott, International Academic Director, Asian Art

‘Chrysanthemums should only be washed by those who are lovers of rare antiques’

Quotation from: Pingshi by Yuan Hongdao, written in the 27th year of the Wanli reign (AD 1599)

The current sale includes two rare Song dynasty dishes which share the feature that their form has been inspired by the shape of a chrysanthemum. Both are from prestigious kilns that made ceramics for the Song courts. One is of delicate white Ding ware and dates to the Northern Song dynasty, while the other has the richly crackled glaze of Guan ware and dates to the Southern Song. The colour of the first has the purity of snow: the glaze of the second has intricate fissures reminiscent of ice – appropriate for a flower that is admired for its resistance to the cold weather of early winter. Both dishes also reflect the exceptional refinement of Song imperial aesthetics.

Their chrysanthemum form is rare amongst Song ceramics from the kilns that were esteemed at the Song court, but nevertheless is in keeping with a tradition of appreciation for this special flower. Chrysanthemums have been greatly admired, especially by Chinese scholars, for centuries. They were used for making wine, for making tea, for medicine, and dried chrysanthemums were put into pillows for their pleasing fragrance and their cooling effect in warm weather. In straitened circumstances, literary men such as Lu Guimeng (d. AD 881) and Su Shi (AD 1037-1101) also recorded eating chrysanthemums – the spring sprouts being tender and succulent, and the summer leaves and stalks being tougher and somewhat bitter. Drinking chrysanthemum wine on the 9th day of the 9th lunar month became popular as early as the Han dynasty. Peter Valder quotes Li in stating that chrysanthemum wine was traditionally made by mixing leaves and stalks, taken from chrysanthemums in full bloom, with glutinous rice and allowing them to ferment – the wine being ready to drink the following autumn. Chrysanthemums were admired by successive emperors from early times, and were grown in the imperial gardens. The Jesuit Pierre-Martial Cibot, who, in the 1770s, researched early Chinese literature relating to chrysanthemums, noted that traditionally the emperor’s plants were shaded with mats from the heat of the midday sun, and that chrysanthemums graced the imperial apartments from mid-autumn to the end of winter.

As early as the 7th century BC Shijing (Book of Odes), through the Liji (Book of Rites), the contents of which date to the Warring States and Han dynasty, and the 3rd century BC Chuci (Songs of Chu or Songs of the South), and continuing into the gongti shi (palace-style poems) of the Six Dynasties period (AD 317-589) flowers in early Chinese poetry were used as symbols of female beauty and of scholarly rectitude, reclusion and nobility. Interestingly, unlike most other flowers, chrysanthemums are not usually associated with women, but with men of strength, integrity and nobility – no doubt in part because their elegant flowers are the only ones to survive the icy winds that herald the onset of winter. The Northern Song dynasty philosopher Zhou Dunyi (AD 1017-73), in his famous work ‘On a Passion for Lotus’ (Ailian shuo), says that he believes that the chrysanthemum is the recluse amongst flowers, comparing it to the over-popular peony. Chrysanthemums are specifically mentioned in the Shijing and in Qu Yuan’s (343-278 BC) poem Li Sao (Encountering Sorrow). In this latter poem there is a much quoted section, which may be translated as:

‘In the morning I drank the dew from magnolias:

In the evening I ate petals that fell from chrysanthemums.

If my mind can be truly pure,

It is of no account that often I am faint from hunger.’

This verse has traditionally been seen as a symbol of virtuous conduct by an official who was forced to leave the court because of the corruption of others. Not surprisingly the chrysanthemum is regarded as one of the ‘four gentlemen’ of plants, along with prunus, orchid and bamboo, which also symbolize nobility of character.

Chrysanthemums are also included in early pharmacopoeias as being beneficial to health, promoting long life, and even immortality. The physician Ge Hong (AD 284-343) wrote of the village of Gangu in Henan province, where the local populace drank water from the nearby brook. Further upstream, chrysanthemum petals fell in profusion into the water, and by the time it reached the village water and petals were mixed. The people of the village were known for their longevity – some of them reportedly reaching the age of 130. However, through their association with certain literary figures, chrysanthemums became symbols of Confucian scholars who refused to compromise their principles and often retreated to a rural existence far from political intrigue. Perhaps the literary figure most closely associated with chrysanthemums is Tao Yuanming (AD 365-427), who is known for his love of chrysanthemums, and who has been depicted with them in paintings from at least as early as the Song dynasty. One such recorded work, painted by Li Gonglin (c. 1041-1106), and inscribed with a poem by Su Shi (1037-1101), was entitled Yuanming at the Eastern Fence. This title was a reference to one of Tao Yuanming’s own poems (the fifth of his ‘Twenty Poems on Drinking Wine), which contains the lines:

‘Gathering chrysanthemums by the eastern fence

I catch a distant glimpse of South Mountain;

The mountain air is wonderful at sunset

And flocks of birds fly home together.’

Chrysanthemums appear with subtle regularity in Tao Yuanming’s poems, sometimes juxtaposed with wine drinking, as in lines from the fourth of his ‘Twenty Poems on Drinking Wine’:

‘Autumn chrysanthemums of beautiful colour,

With dew on my clothes I pluck their blossoms.

I float them in wine to forget my sorrows,

Leaving thoughts of the world far behind.’

One of his most famous poems is Returning Home, which describes his feelings on coming back to his home in the country, after retiring from his post as an official at the age of 41, with the intention to spend his days farming and writing poetry. In the poem Tao sees his home and exclaims:

‘The three paths have almost disappeared,

But the pines and the chrysanthemums are still here.’

It may also be the case that when in his poem Written on the Ninth Day of the Ninth Month of the Siyou Year [AD 409] Tao Yuanming says:

‘What can I do to restore my spirits?

Only enjoy drinking unstrained wine.’

he was referring to chrysanthemum wine, since chrysanthemums were especially associated with autumn and the ninth day of the ninth month.

This admiration of chrysanthemums for their fragrance, beauty, resilience and health-giving properties led in the Tang dynasty to specific cultivation and development of these remarkable plants. Mention of Chinese chrysanthemums in early literature suggests that only the yellow variety were originally known, however, from the 8th century poets made admiring references to white chrysanthemums. White chrysanthemums were supposed to be able to endure particularly cold weather, and were said to have been imbued with ‘the soul of the sky and earth’. Tea made from white chrysanthemums is said to be especially fragrant and refreshing. It is possibly these delicate white chrysanthemums which provided the inspiration for the two Song dynasty dishes in the current sale. In regard to these Song dynasty dishes, it is probably worth noting that what appears to be the first of many monographs on chrysanthemums, entitled Ju Pu (Treatise on Chrysanthemums), was published by Liu Meng towards the end of the Northern Song dynasty in AD 1104. Liu Meng lists 35 varieties of chrysanthemum, and two of these are called ‘jade basin’ and ‘silver bowl’, the names of which have resonance with the appearance of the Guan and Ding ware dishes in the current sale.

In the visual arts, flowers appear to have begun to be selected as independent subjects for painters during the Six Dynasties period, as can be seen in the works of artists such as Gu Kaizhi (c. 344-406) and Zhang Sengyu ( act. 500-550). However, as Robert Harrist has noted, it was during the 10th century that the artists Huang Quan (903-968) of the Shu kingdom and Xu Xi (act. 960-c. 975) of the Southern Tang kingdom ‘brought flower painting to a new perfection’. Harrist has also pointed out that judging from the entries in the Xuanhe huapu (Painting Catalogue of the Xuanhe Era [AD 1119-1125]), by the end of the Northern Song dynasty flowers were the most popular subject. It is interesting to note that although chrysanthemums are not as common as some other flowers in Song dynasty paintings, they are included amongst the flowers on the famous Song dynasty hand-scroll One Hundred Flowers preserved in the Palace Museum, Beijing. They are also the primary subject of a charming anonymous 12th century Southern Song dynasty fan painting in ink and colour on silk entitled Peach Blossom Chrysanthemums, which has an inscription attributed to Empress Wu (AD 1115-1197, consort of Emperor Gaozong), in the collection of the Palace Museum, Beijing. The painting depicts delicate pink and white chrysanthemums in a dark green vase, which is itself placed in a stand, and the fan has numerous seals affixed, including the kungua seal signifying an empress.

Chrysanthemums appear as decoration on Chinese ceramics at least as early as the Northern Qi period (AD 550-577). While lotus was the dominant floral motif in this and the succeeding Sui and Tang dynasties, sprig-moulded chrysanthemum blossoms adorn the second register of the neck of a Northern Qi celadon-glazed vase in the collection of the Palace Museum, Beijing. Chrysanthemums also appear among the sprigged motifs in the lowest register of decoration on a Tang dynasty ewer in the same collection. There is additionally a green-glazed Sui dynasty bowl in the Palace Museum which has been identified in publications as having rows of lotus petals carved into its exterior. However the shape and arrangement of the petals suggests that the decorator’s intention may have been to depict chrysanthemum petals – in this case representing the whole bowl as a chrysanthemum flower. If this interpretation is correct, this Sui dynasty bowl would be one of the earliest ceramic open-wares to be made in the form of a chrysanthemum.

During the Song dynasty vessels made in chrysanthemum form became popular in a number of different media. The form of dishes in both silver and lacquer drew inspiration from the flower, as did rare fine ceramics. Silver and silver-gilt bowls and dishes in chrysanthemum form have been excavated from a number of Southern Song sites, including one dated to AD 1190 in Sichuan province, and another dated 1226 in Fujian province, as well as a cup stand from another Fujian site. A Northern Song lacquer dish of similar flat-based form to the current Ding ware dish was unearthed in Jiangsu province. Boxes in chrysanthemum form were also made in both silver and porcelain in the Song dynasty. However the greatest proportion of Song dynasty flower-form ceramics was made in the shape of mallow or lotus. Nevertheless a small number of vessels made for the court took their inspiration from chrysanthemums. Interestingly there is a Ru ware dish with multiple petals and a flat base, excavated in Henan, which has been described in publications as being ‘in the shape of a lotus flower’ (fig. 1). However, lotus petals are almost invariably depicted in the Song dynasty with slight points at the end of each petal, and the petals on this bowl are both numerous and rounded, suggesting that it may in fact be based on a chrysanthemum. The Ru dish is of similar size to the Guan ware dish in the current sale. A small number of Song dynasty chrysanthemum-shaped dishes are preserved in the Palace collections. A Ge ware dish of very similar form to the Guan ware dish in the current sale, although slightly smaller, is in the collection of the Palace Museum, Beijing, and another similar Ge ware chrysanthemum dish is in the collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei (fig. 2). A Guan ware dish with even more petals and a flatter base with distinct foot ring, is in the collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei, while a sixteen-petalled Guan ware brush washer with flat base is in the same collection. A chrysanthemum dish with crackled glaze similar to the one in the current sale, but possibly representing one of the Ge ware dishes still in the Palace collections, also appears on the Yongzheng Guwan tu hand-scroll in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum, which is dated to 1729, and which illustrates antiques from the imperial collections in a range of media (fig. 3). It is also worth noting that, in the early 20th century, such was the prominence of the current Guan ware chrysanthemum dish that, when it was exhibited at the Musee de l’Orangerie in 1937, almost all of the other vessels with which it shared a case were Ru and Guan wares from the collection of Sir Percival David.

In the case of Ding wares, while a number of chrysanthemum-shaped dishes dating to the Jin dynasty are known, Northern Song dynasty examples are very rare. A similarly-sized, flat-based, Northern Song Ding ware dish with 12-petalled rim was unearthed at the Ding kilns at Jianciling during excavations in 2009-2010. A flat-based multi-petalled Ding ware dish of similar form to the dish in the current sale was published in the Qianlong Emperor’s album Zhen Tao Cui Mei (Precious Ceramics of Assembled Beauty), where it was dated to the Song dynasty (fig. 4). As the dish in the album has moulded decoration on the interior, it is likely to date to the Jin dynasty, but it is interesting to note that the dish itself appears to have been preserved in the National Palace Museum, Taipei. A similarly lobed Ding-type dish, but standing on a short straight foot, was excavated in 1970 from the tomb of Wang Ze, dated AD 1053, in Fengtai district, in Beijing. A slightly smaller Ding-type chrysanthemum-shaped dish also standing on a small straight foot was formerly in the collection of Carl Kempe, while a similar Yaozhou dish with a small straight foot was excavated in Binxian, Shaanxi province. A much smaller Ding ware dish with 12 petals and a flat base was also formerly in the Carl Kempe collection. Chrysanthemum-shaped dishes with flat bases are known from other Northern Song kilns in north China. A smaller example from the Yaozhou kilns is in the collection of the Ashmolean Museum, and a small brown-glazed example, probably from the Henan kilns, was formerly in the Carl Kempe collection.

The current Ding ware chrysanthemum dish is of particular interest, and especially rare, as it appears to have been fired standing upside-down on the tips of its petals, which are unglazed. As the dish is delicately potted, and thus would have been liable to warp in the firing, this was a risky strategy on the part of the potter. However, the fully-glazed base adds to the sophistication of the vessel. Ts’ai Mei-fen of the National Palace Museum has argued that Ding wares did not necessarily have unglazed rims in order to allow them to be fired upside-down, but in order to prepare them for fashionable metal bands. However, this does not appear to have been the case with the current dish, since only the tips of the petals on which it would have stood in the kiln are unglazed. Otherwise the dish is fully glazed. In view of the rarity of this firing method and the high risk of failure, it is tempting to wonder if this dish was part of a special commission from a personage of great importance – perhaps an emperor.

1 Peter Valder, The Garden Plants of China, London, 1999, pp. 238-9, quoting Li, Hui-Lin, The Garden Flowers of China, New York, 1959

2 Pierre-Martial Cibot, ‘Le Kiu-hoa ou la Matricaire de Chine’, Memoires concernant l’histoire, les sciences les arts, les moeurs, les usages, etc., des Chinois: par les missionaires de Pekin – Notices de quelques Plantes, Arbrisseaux, etc. de la Chine, Beijing, 1778, pp. 455-61.

3 Wang Jiaxi, and Ma Yue, (trans. Deng Xin), China’s Rare Flowers, Beijing, reprint 1995.

4 This treatise, along with two other Song dynasty treatises on chrysanthemums by Fan ChengdaSjand Shi Zhengzhiv, is included with Wang Guan’s Yangzhou shao yao pu, Shanghai, 1939.

5 Christopher Thatcher, ‘Flowers and Trees’, The History of Gardens, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1979, p. 55.

6 Robert E. Harrist, ‘Ch’ien Hs?an’s Pear Blossoms: The Tradition of Flower Painting and Poetry from Sung to Yuan’, Metropolitan Museum Journal, no. 22, New York, 1987, p. 54.

7 Ibid.

8 Illustrated by Yuan Jie in Calligraphy and Painting Gallery of the Palace Museum, Part IV, Beijing, 2009. The scroll is 16.79 m. long.

9 Illustrated by Hui-Shu Lee in Empresses, Art, & Agency in Song Dynasty China, Seattle and London, 2010, p.141, pl. 3.13.

10 Illustrated in The Complete Collection of Treasures of the Palace Museum – 31 – Porcelain of the Jin and Tang Dynasties, Hong Kong, 1996, pp. 62-3, no. 57.

11 Ibid. p. 176, no. 162.

12 Ibid., p. 66, no. 60.

13 Illustrated by the Nezu institute of Fine Arts in Colors and Forms of Song and Yuan China; Featuring Lacquerwares, Ceramics, and Metalwares, Tokyo, 2004, pp. 183-4, no. 48a.

14 Ibid., p. 185, no. 51a.

15 Ibid., p. 182, no. 42b.

16 Ibid. p. 175, no. 24b.

17 Ibid., exhibits 34 and 35.

18 Illustrated in Northern Song Ru Ware: Recent Archaeological Findings, Museum of Oriental Ceramics, Osaka, 2009, pp. 100-101, no. 38.

19 Illustrated in The Complete Collection of Treasures of the Palace Museum – 33 – Porcelain of the Song Dynasty (II), Hong Kong, 1996, p. 88, no. 80.

20 Illustrated in Porcelain of the National Palace Museum – Ko Ware of the Sung Dynasty Book II, Hong Kong, 1962, no. 45.

21 Illustrated in Catalogue of the Special Exhibition of Sung Dynasty Kuan Ware, Taipei, 1989, no. 95.

22 Illustrated in Porcelain of the National Palace Museum – Kuan Ware of the Southern Sung Dynasty Book II, Hong Kong, 1962, no. 20.

23 Victoria and Albert Museum accession number E.59-1911.

24 Moulded examples in the National Palace Museum, Taipei are illustrated in Catalogue of the Special Exhibition of Ting Ware White Porcelain, Taipei, 1987, nos.92-98.

25 A diagram of the piece is shown by Qin Dashu, et al., in ‘Dingyao Jianciling yaoqu fazhan jieduan chutan’, Kaogu, 2014, no. 3, p. 86, fig. 9.1.

26 Both the Ding ware dish and the album leaf are illustrated in Obtaining Refined Enjoyment: The Qianlong Emperor’s Taste in Ceramics , Taipei, 2012, pp. 216-7, no. 100.

27 Illustrated in Kaogu, 1972, no 3, p. 36, fig.2.

28 Illustrated by Bo Gyllensvard in Chinese Ceramics in the Carl Kempe Collection, Stockholm, Goteborg and Uppsala, 1964, p. 136, no. 431.

29 Illustrated by Shaanxi Provincial Museum in Yaoci tulu, Beijing, 1957, pls. 28 and 29.

30 Illustrated by Bo Gyllensvard, op. cit. p. 139, no. 443.

31 Illustrated by Mary Tregear in Song Ceramics, London, 1982, p. 115, pl.132.

32 Illustrated by Bo Gyllensv?rd, op. cit. p. 95, no. 269.

33 Ts’ai Mei-fen, ‘A Discussion of Ting Ware with Unglazed Rims and Related Twelfth-Century Official Porcelain’, Arts of the Sung and Yuan, New York, 1996, pp. 109-31.

THE PROPERTY OF AN ASIAN COLLECTOR

![[临渊阁]天地一家春](https://www.antiquekeeper.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/cropped-Asian-Art-Wallpaper-Painting3-6-2.jpg)