Description

宋 贴花旋纹 牡丹花蝶鸟纹六系陶罐

长沙窑始于初唐,盛于中晚唐,终于五代,时间延续300多年。其烧制出来的瓷器品种丰富、美观精致、实用性强。这些瓷器在青釉下加绘彩色花纹,冲破唐以前单色青釉一统天下的局面,开拓了一条崭新的发展之路。长沙窑是我国釉下彩绘的第一个里程碑,为唐以后的彩瓷发展奠定了基础,是我国彩瓷工艺的骄傲。

长沙窑的产品,以碗、盘、壶、罐、盂为主,品种比较单一。后期除增加冼、枕、盏托盒等日常用具,前期腹体圆浑,短颈,短流。至晚唐五代时期,其腹部变为瓜棱腹,颈部细长,流呈圆管状,柄为双曲柄,表现出一种线条艺术的韵味和意境。枕在长沙窑青瓷釉下彩绘中也具有典型性,器形较小,有方形、长圆形、腰圆形和兽形等。

长沙窑釉下彩绘,早期色彩比较单调,只有釉下褐彩,或釉下绿彩,其后出现褐、绿两彩,或褐、绿、红多种色彩并现的情况。这几种色彩因交替或重复运用,使彩色产生多变效果,并利用釉料在高温中与瓷胎相互渗透的原理,形成深浅浓淡的层次。纹饰也由以斑点组成的简单几何图案,变成描绘花鸟、人物、山水以及诗文的画面。这些画面虽然简单,但意境协调,充满勃勃生机,它融唐代花鸟画与书法艺术于陶瓷装饰之中,融自然生态于图案程式中,为后世瓷器的彩绘装饰,开辟了广阔途径。

长沙窑青瓷釉下彩绘图案非常丰富,包括人物、花鸟、花草和各种动物。鸟类图案有雁、长尾鸟、凤鸟、雀鸟等;花草图案有莲花、宝相花等。在各种图案中以动物、花鸟画最具特色,尤以鸟的画法最具艺术性。在绘画技巧上长沙窑青瓷釉下彩绘,常以粗线勾出大体形态,然后用细线描勾细部轮廓部分,小草、枝叶则采用没骨画法。以在长沙窑青釉褐绿彩壶为例,腹部花鸟图案为一只昂首翘尾的小鸟,和几枝疏朗的花叶。鸟用绿彩粗线勾画出轮廓,嘴、翅膀和羽毛则施褐彩细细描绘。花叶以没骨画法由褐彩作轮廓,中间填绿彩,整个画面虽草草几笔,但小鸟的神态栩栩如生,颇得写意画之妙。

用诗文、书法艺术作为瓷器的一种装饰,题材相当丰富,也是唐代长沙窑釉下彩绘的一大特色

长沙窑瓷器中,除釉下彩绘外,还采用模印、贴花等手法装饰器物,也就是将纹样贴在器物的腹部,并涂以褐色彩斑烧成。

参考:usedVictoria.ca

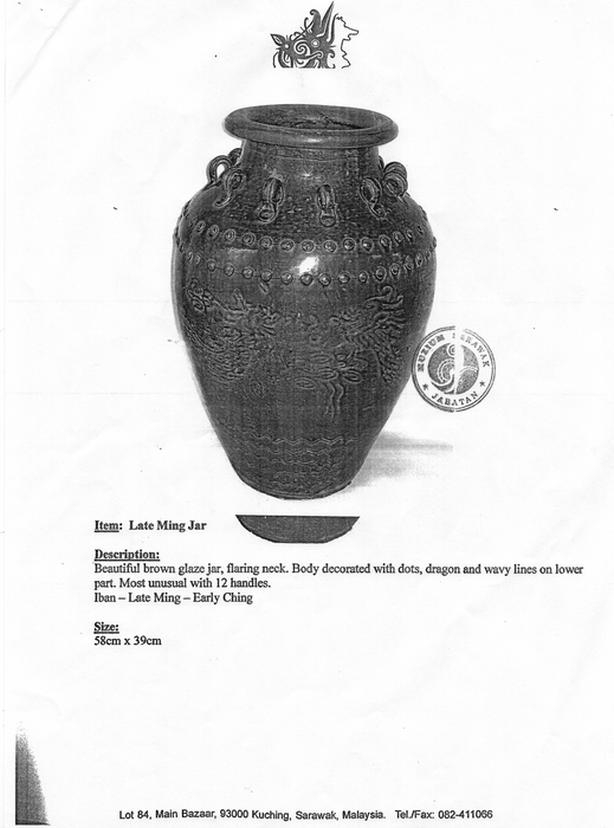

16th Century (C.1368-1644)

Antique Late Ming Early Ching Dynasty

Chinese Jar

$1,500

16th Century (C.1368-1644) Antique Late Ming Early Ching Dynasty Chinese Jar

Very rare to find this in North America. We found this 16th century jar while touring Kuching, Borneo. It was imported by us as part of a Dayak Antiquity Collection authorized for export by the Sarawak Museum. It is in remarkably good condition for its 500+ years.

The glaze is an amber colour.

Size: 23 inches tall x 16 inches wide

参考:苏富比

CHINA / 5000 YEARS

CHINESE CERAMICS: A PRIVATE COLLECTION

Lot 1387 A molded ‘Yue’ celadon-glazed ‘medallion’ jar, Sui dynasty

隋 越窰青釉貼花罐

September 26, 2023

Estimate 3,000 – 5,000 USD

Lot Sold 3,810 USD

A molded ‘Yue’ celadon-glazed ‘medallion’ jar

Sui dynasty

隋 越窰青釉貼花罐

Height 8¾ in., 22.4 cm

Condition Report

Scattered chips and losses, particularly to the loop handles (now missing) and foot. The vase is slightly unevenly potted. 整體見細磕,尤見於耳處(現已缺失)及足。整體器身略欠工整。

Provenance

Acquired prior to 2000.

参考:佳士得

19 3月 2015 | 現場拍賣 11421

錦瑟華年 – 安思遠私人珍藏

第四部分:中國工藝精品 ─ 金屬器、雕塑及早期瓷器

拍品 799

A CHANGSHA BROWN-GLAZED JAR

唐 長沙窯褐釉貼花雙繫罐

CHINA, TANG DYNASTY, 9TH CENTURY

成交價 USD 6,250

估價 USD 4,000 – USD 6,000

來源

The Collection of Robert H. Ellsworth, New York, acquired in Hong Kong, 1987.

狀況報告

We have sought to record changes in the condition of this piece acquired after its initial manufacture.

– There is some glaze degradation to the edges and reliefs.

– There are some small areas of retouch to the rim.

– There is a vertical firing crack under the glaze of one of the appliques.

– There are some expected glaze imperfections.

参考:佳士得

16 3月 2015 | 現場拍賣 11418

錦瑟華年 – 安思遠私人珍藏

第一部分:重要珍藏 ─ 包括印度、喜馬拉雅及東南亞工藝精品,以及中國與日本工藝精品

拍品 17

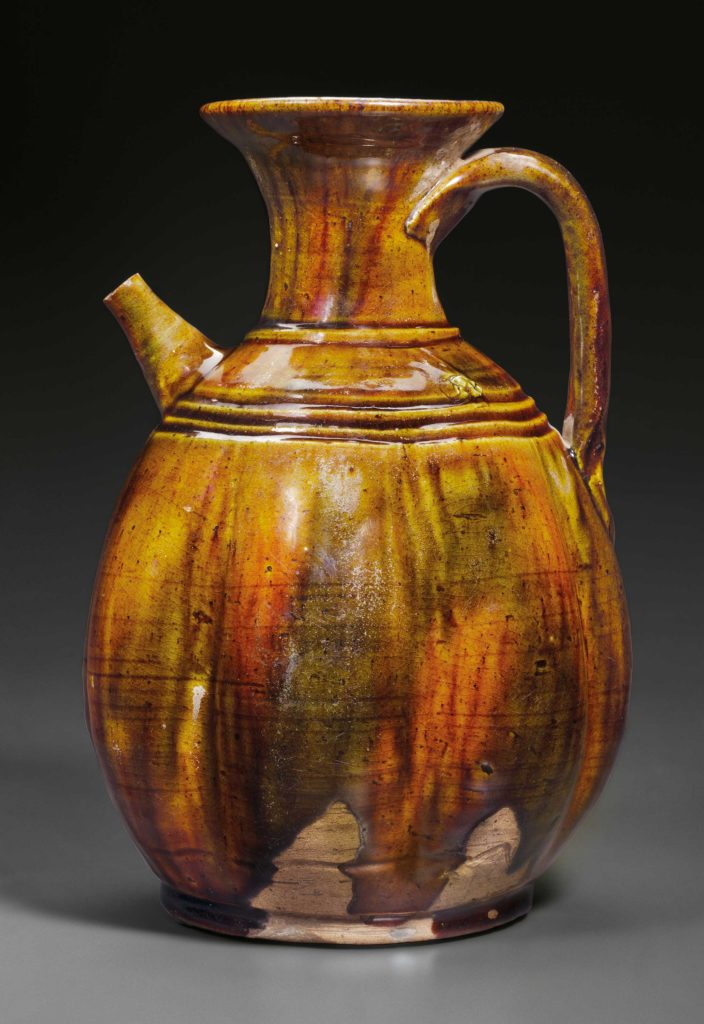

A VERY RARE SANCAI-GLAZED POTTERY PHOENIX-HEAD EWER

唐 三彩鳳首水注

CHINA, TANG DYNASTY (AD 618-907)

成交價 USD 437,000

估價 USD 100,000 – USD 150,000

唐 三彩鳳首水注

CHINA, TANG DYNASTY (AD 618-907)

來源

The Collection of Robert H. Ellsworth, New York, acquired in Hong Kong, 1990.

注意事項

This lot is offered without reserve.

狀況報告

We have sought to record changes in the condition of this piece acquired after its initial manufacture.

– There are some chips to the raised decoration, the two tails of the birds are chipped, and one has restoration.

– There is a restoration to the foot and base of the globular body.

– There are small restoration to the linghzi in relief, and some restoration to the bell flower.

– The neck with a triangular restored crack.

– The restorations are well done and difficult to see. There may be some further more minor areas of restoration.

拍品專文

This magnificent and rare ewer is a fine example of the successful melding of inter-cultural creative traditions – combining Chinese artistry and technology with inspiration provided by the arts of the Islamic West. In the late 6th century the Sui dynasty Yangdi Emperor (AD 569-618) opened diplomatic relations with the Sasanian Persian Empire (AD 224-651). While the main purpose of this diplomatic initiative was to stimulate trade, while also enlisting the help of Sasanians in keeping at bay the increasingly powerful nomadic tribes from the north and west, it would also have a profound effect on Chinese culture – especially the decorative arts and music. Amongst the Sasanian arts most admired by the Chinese was metalwork, and indeed metalwork from that region had been famous long before the Sasanian period – the Achemenid (550–330 BC) and Parthian (247 BC – AD 224) Empires were also known for their fine metalwork. From the late 6th century, however, fine gold and silver vessels, along with a number of Persian craftsmen entered the Tang capital Chang’an (modern Xi’an) and provided inspiration for Chinese craftsmen working in a range of media. One of the areas in which this inspiration can be seen is 8th century Chinese earthenwares, often with sancai (three colour) lead-fluxed glazes. One of the forms which gained especial popularity was the high-footed ewer.

While its overall shape is clearly inspired by Sasanian metalwork forms, several features of the current ewer continue Chinese traditions. Bird-heads had been used on Chinese vessels made at the Yue kilns as early as the Six Dynasties period (AD 220–589), but by the Sui dynasty (AD 581-618) elaborate bird’s heads with hawk-like beaks were already appearing on Chinese ceramic vessels. An example of a 6th-7th century celadon-glazed ewer with such a head, which is decorated with sprig-moulded roundel containing western figures and other imported features, is in the collection of the Palace Museum, Beijing (illustrated in The Complete Collection of Treasures of the Palace Museum – 31 – Porcelain of the Jin and Tang Dynasties, Hong Kong, 1996, pp. 186-7, no. 172). In addition, there are several aspects of this ewer which set it apart from the more commonly found Tang sancai phoenix-head ewers. Firstly, many such ewers have bodies which are both somewhat pear-shaped – as are the Sasanian metalwork ewers – and slightly flattened; having been made using moulds and luted vertically (see for example the ewer excavated at Sanqiao, Xi’an in 1959, illustrated in Treasures from Chang’an: Capital of the Silk Road, Hong Kong, 1993, no. 30). The body of this ewer, however, is virtually spherical, and reflects the Tang potter’s skill in throwing this form. Also, while it is not unusual to have a slightly raised torque around the shoulder of a vessel which has its origins in metalwork, this vessel has a complementary raised band around the lower part of the spherical body. Instead of the more usual splashed effects, the decorator has used the glaze colors to effectively highlight both these raised bands by giving them a cream base color while the leaf, or palmette, motifs are green, in contrast to the main area of the body which has an amber glaze.

The second area of the ewer which contrasts with the majority of phoenix-head ewers is the handle. While a number of the handles of such ewers are of plant form, these are not usually particularly naturalistic and the flower on the stem most frequently forms the opening at the top of the vessel. On this ewer, however, the bell of the flower cups the back of the phoenix’s head. Thirdly, it is rare to find a well-formed sphere held in the bird’s beak, which itself is not normally so realistically rendered. The intricacies of both the bird’s head and the floral handle are also exceptionally detailed. The choice of flower for the handle is both unusual and interesting since versions of this type of bell flower can also be seen on early Chinese embroideries such as the 3rd century BC embroidered silk covering for a woolen felt saddle blanket excavated from kurgan 5 at Pazyryk, in the Altai region of south-western Siberia (illustrated by Sergei I. Rudenko in Frozen Tombs of Siberia: the Pazyryk Burials of Iron Age Horsemen, (translated by M. W. Thompson), Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1970, pp. 174-178, pl. 178), and the Warring States embroidered robe excavated in 1982 from a tomb at Mashan in Hebei province (illustrated in Zhongguo meishu quanji –gongyi meishu bian 6 – yin ran zhi xiu (xia), Beijing, 1985, pp. 30-1, no. 24). It is not a flower that often appears in ceramics.

Links with fine silks can also be seen in other aspects of the design of this ewer, although their origins can, in both cases be traced to Sasanian silver. Naturalistically depicted birds and distinctive clouds, similar to those above the equestrian figures on the current ewer, can be seen woven into a piece of Tang dynasty polychrome brocade excavated in 1968 at Astana in Xinjiang (illustrated in Zhongguo meishu quanji –gongyi meishu bian 6 – yin ran zhi xiu (xia),op. cit., pp. 166-7, no. 157). A hunting scene with equestrian huntsmen, chasing their quarry through landscape elements accompanied by birds and similarly-shaped clouds, appears on a Tang dynasty printed silk gauze, also excavated in 1982 at Astana (illustrated ibid., p. 143, no. 132).

As Jessica Rawson has noted, palmette borders such as those seen on the current ewer can trace their origins back to Greek vases (see J. Rawson, Chinese Ornament: The Lotus and the Dragon, London, 1984, p. 215), but this inspiration would almost certainly have entered the Chinese potters’ repertoire via Persian metalwork, on which the design sometimes appears as s band around the shoulder of pear-shaped vessels. The formal shrubs over which the riders jump in the main band on the current ewer also have their origins in Persian metalwork, but a close look at the rocky outcrops which rise from the base line of the main decorative band between the riders reveals a relief similarity to the three-dimensional form of the so-called boshanlu ‘magic mountain’ censers of the Han dynasty.

While the object held by the equestrian has previously been described as a sling, two other interpretations should also be considered. If the equestrian figure is indeed a huntsman, then the long pole with a loop on the end, which he brandishes with such fervour, may be a snare rather than a sling. A sling is shown on the Astana printed gauze discussed above, and the shape differs markedly from the article held by the riders on this ewer. The third possibility is that the rider is a polo player and that the stick he holds aloft is a polo stick. As can be seen from the mural on the west wall of the entrance corridor of’ the AD 706 tomb of Li Xian (the crown prince Zhanghuai), near Xianyang, Shaanxi province, polo players at the Tang capital of the 8th century played using a long, slender, stick with a curled – although not looped – end (illustrated in Tang Lixuan mu bihua, Beijing, 1974, pl. 15). Like horse racing, polo has been called ‘the sport of kings’ and was introduced into China, probably by the Xianbei tribes of the north, at some time between the 3rd and 6th centuries. Polo became very popular with the Chinese elite and was played by both men and women. An interestingly similar scene to that depicted on the ewer can be seen on the exterior of one lobe of an eight-lobed, ring-handled gilt-silver cup excavated in 1970 from an 8th century hoard at Hejiacun in the southern suburbs of Xi’an, Shaanxi province (illustrated by Dayton Art Institute in The Glory of the Silk Road – Art from Ancient China, Dayton, Ohio, 2003, p. 195, no. 104. However, it is clear that the scene on the gilt-silver cup is intended to depict hunting.

The horses on this ewer are shown in the position known as the ‘flying gallop’ – with both forelegs and back legs outstretched, a configuration that is not known in real horses, but which has been used by artists from different cultures for centuries in order to convey the impression of speed. The fact of this being an artistic impression, rather than an accurate portrayal, of a horse’s gallop was finally proved by the English photographer Eadweard James Muybridge, who in 1877 and 1878, using multiple cameras, produced sequential photographs of a horse galloping. Even then some viewers did not believe the photographs could be accurate. The subject, as applied to Chinese art, was first addressed by Berthold Laufer in his book Chinese Pottery of the Han Dynasty, Leyden, 1909.

This handsome ewer is thus not only a Tang dynasty vessel made by a craftsman of consummate skill, it also reflects a range of sources of inspiration and is worthy of detailed art historical study.

The result of Oxford thermoluminesence test no. 566r79 is consistent with the dating of this lot.

参考:佳士得

25 3月 2015 | 網上拍賣 11220

The Collection of Robert Hatfield Ellsworth Volume VII: Chinese Works of Art Online

拍品 8034 遼 黃綠釉瓜式注壺

成交價 USD 8,125

估價 USD 3,000 – USD 5,000

詳情

A GREEN AND AMBER-GLAZED LOBED EWER

CHINA, LIAO DYNASTY (AD 907-1125)

The lobed, oviform body carved with grooves around the shoulder below a bow-string band at the base of the waisted neck, covered overall in an amber and green streaked glaze

5 ¾ in. (19 cm.) high, box

参考:佳士得

31 5月 2016 | 現場拍賣 13755

開元大觀

拍品 3104

A RARE SANCAI-GLAZED ‘FLORAL MEDALLION’ JAR

VARIOUS PROPERTIES

唐 三彩貼花寶相花紋罐

TANG DYNASTY (618-907)

成交價 HKD 4,360,000

估價 HKD 1,800,000 – HKD 2,600,000

唐 三彩貼花寶相花紋罐

TANG DYNASTY (618-907)

細節

唐 三彩貼花寶相花紋罐

11 3/4 in. (30 cm.) high

來源

日本私人藏家,於1998年購自香港

紐約佳士得,2003年3月26日,拍品197號

狀況報告

謹請注意,所有拍品均按「現狀」拍賣,閣下或閣下的專業顧問應於拍賣前親自查看拍品以評鑑拍品之狀況。

– 整體品相良好

– 九小塊圓形樣本曾自底部邊緣取出用於熱釋光測試,經填補

拍品專文

同類三彩寶相花紋罐可比安宅英一舊藏一件,現藏大阪市立東洋陶瓷美術館,被列為日本重要美術品,著錄於東京1976年出版《龍泉集芳》,第一集,編號226(圖一); 以及芝加哥藝術學院博物館藏一件,載於繭山順吉編,1960年東京出版,《歐米蒐藏中國陶瓷圖錄》,第5頁,編號5。 另可比一件綠釉寶相花紋罐,載於1976年小學館出版《世界陶瓷全集11:隋.唐》,48頁,編號33。

此器經牛津熱釋光測年法測試(測試編號 666×55),證實與本圖錄之定年符合。

参考:浙江南北拍卖有限公司

2007-07-01 2007

春季艺术品拍卖会

青瓷之美

LOT号: 0660 唐 长沙窑褐彩执壶

尺寸 高度20厘米,直径6.3厘米

估价 RMB 40,000-50,000

流拍

说明:壶矮颈小口,圆鼓腹,八方短流。对边有执把,把两旁有纽,可提携。腹壁四面压印折枝葡萄串,上有褐彩。此壶为酒器,器形完整规范。长沙窑是唐代名窑,以烧制青瓷及褐彩贴花装饰器见长。

参考: 韩国国立中央博物馆藏

馆藏编号:德福5160

唐 长沙窑贴塑人物执壶

唐朝(公元618年—公元907年)

日期尺寸:高19.6厘米,直径17.7厘米.

官方描述:

长沙窑(Changshayo)是当时不良 主歌的继承和发展,对后来被涂成白色瓷器的釉下彩绘(Yuhachaehoe)工艺产生了重大影响。这个水壶是用柔软的土壤制成的青瓷。它的 嘴和脖子短,腹部大,柄小,底部宽。手柄和耳朵上有两排凹槽。它覆盖着蓝褐色釉,并在手柄下方和两侧的两只耳朵下方饰有人物图案 ,并在其周围覆盖了红褐色釉。

![[临渊阁]天地一家春](https://www.antiquekeeper.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/cropped-Asian-Art-Wallpaper-Painting3-6-1.jpg)