Description

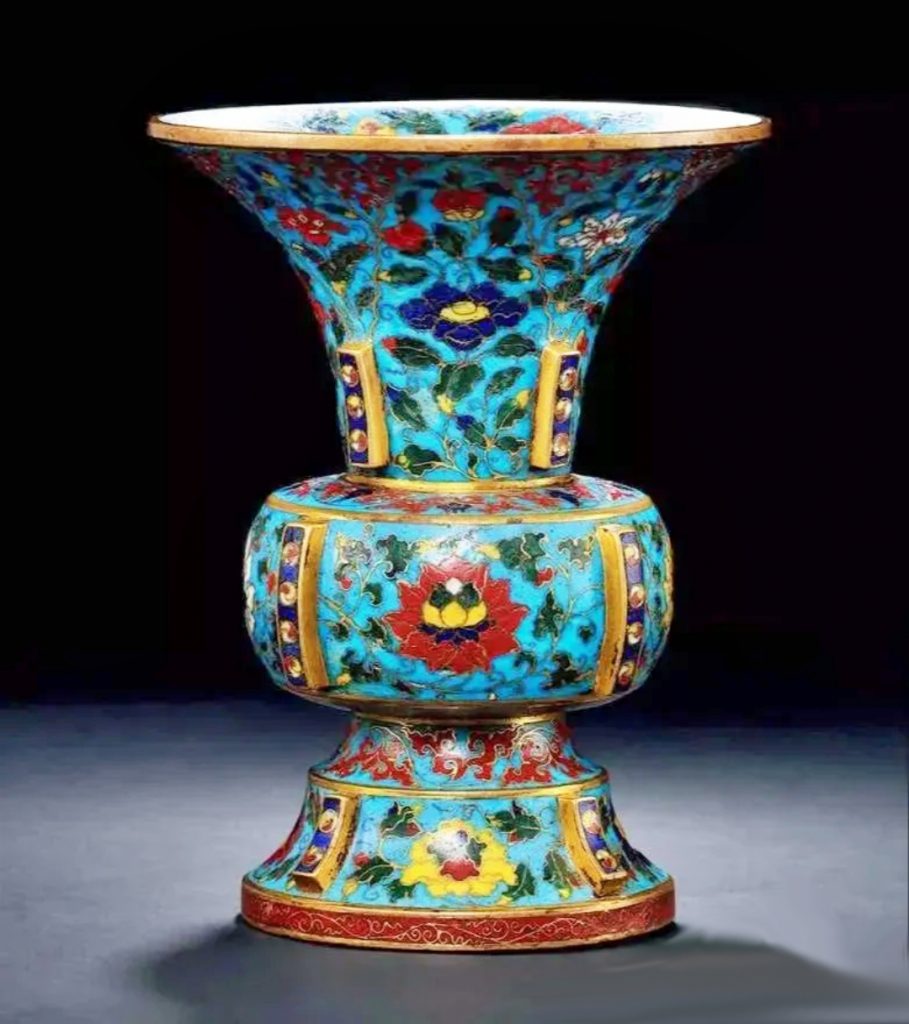

明 铜胎景泰蓝珐琅彩灯台 灯柱 烟缸

参考:佳士得

現場拍賣 7997

2011年11月8日

中國瓷器及工藝精品

拍品 406

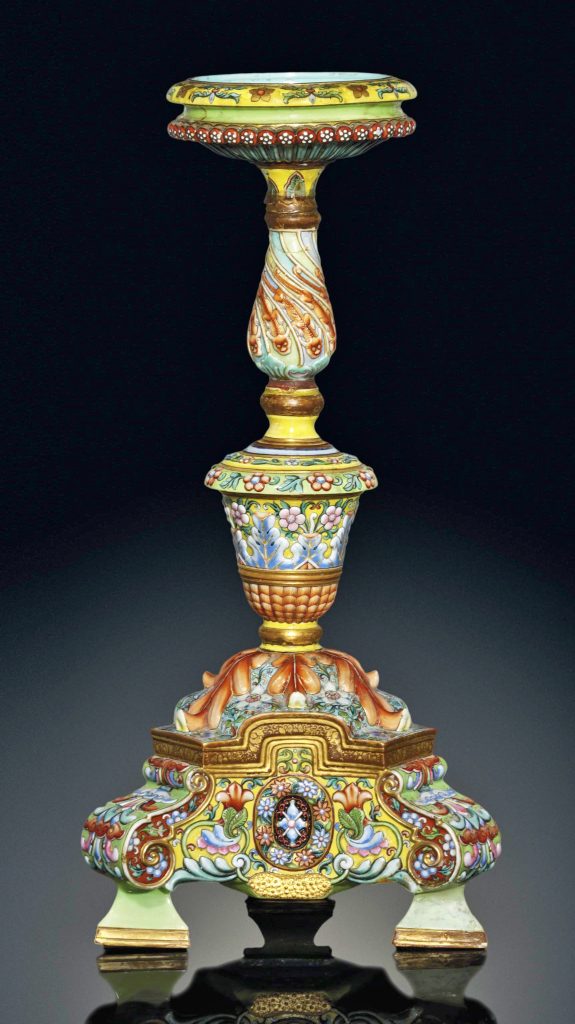

A VERY RARE FAMILLE ROSE MOULDED CANDLESTICK

粉彩花卉紋燭臺 四字篆書款

清雍正

清雍正

成交價 英鎊 1,329,250

估價 英鎊 40,000 – 英鎊 60,000

狀況報告

The base has been drilled through the seal mark and one foot has been broken off and restored.

The stem has been broken off from the base and broken into two further sections (the section below the drip pan with minor losses) and restored as seen in catalogue illustration.

The drip pan has been broken into two sections and restored.

拍品專文

最初,这件烛台是由五件套佛堂祭器的一部分组成,包括一个香炉、两个花瓶和两个烛台,这些器物通常用于佛教寺庙。这件烛台不仅展示了陶工的高超技艺,同时也体现了彩釉工艺的精湛技法。由于烛台形制较为脆弱,因此在此类祭器中存世最为稀少。

一组三件套的雍正祭器(包括一个香炉和两个花瓶),与本品在装饰和造型上类似,曾由已故H. S. 斯特恩上校遗产收藏,并于1982年4月7日在本行拍卖,拍品编号62。W. T. 沃尔特斯收藏的一件花瓶曾由S. W. 布谢尔在《东方陶瓷艺术》(1980年版)中出版,图版XX;另一件花瓶则于2001年3月20日在本行纽约拍卖,拍品编号273。

上海博物馆收藏的一件与之极为相近的花瓶,刊载于《中华陶瓷全集:景德镇彩绘瓷器》,上海,1981年,第21卷,图版99。

Originally forming part of a five-piece altar set comprising a censer, two vases and two candlesticks, which would have been used in a Buddhist temple, this candlestick demonstrates not only the skill of the potter but also of the enameller. Probably the rarest of the forms still existing from such altar sets are the candlesticks due to their vulnerable form.

A Yongzheng three-piece altar set (a censer and two vases) similarly decorated and moulded to the present lot, from the Estate of the late Colonel H. S. Stern, was sold in these rooms 7 April 1982, lot 62. A vase from the collection of W. T. Walters is illustrated by S. W. Bushell, Oriental Ceramic Art, 1980 ed., pl. XX; and another vase was sold in in our New York Rooms, 20 March 2001, lot 273.

A closely related vase in the Shanghai Museum is illustrated in Zhongguo taoci quanji; Jingdezhen caihui ciqi (The Great Treasury of Chinese Ceramics; Jingdezhen Painted Porcelain), Shanghai, 1981, vol. 21, pl. 99.

参考:佳士得 現場拍賣 7997

中國瓷器及工藝精品

拍品 55

A MAGNIFICENT AND RARE PAIR OF IMPERIAL CLOISONNÉ ENAMEL AND PAINTED SILK LANTERNS

御製掐絲琺瑯嵌絹畫宮燈一對

清乾隆

清乾隆

成交價 英鎊 385,250

估價 英鎊 200,000 – 英鎊 300,000

狀況報告

One top section:

There are two dents to the top section resulting in losses to the enamels.

There are further smaller losses to the enamels throughout.

One painted panel has been torn and amended, the other three with minute water marks and small tears.

One lower section:

There are small dents to the base resulting in losses to the enamels.

There are small areas of losses to the enamels throughout.

The other top section:

There are two dents to the top section resulting in losses to the enamels.

There are minor dents to the frames surrounding the paintings.

There are tears and water damages to three panels.

The other lower section:

There are small dents to the base resulting in losses to the enamels.

來源

The Farrow Collection, Jersey, Channel Islands.

拍品專文

绘画与珐琅艺术的精美结合

罗斯玛丽·斯科特(Rosemary Scott),国际学术总监,亚洲艺术

这对精美的宫灯巧妙地融合了珐琅工艺和丝绸绘画的技艺。珐琅匠人精心制作出镂空的掐丝珐琅灯座,而画师则在丝绸上绘制出八幅雅致的画面,使微光透过画面熠熠生辉。

带有大面积镂空装饰的掐丝珐琅作品极为罕见。虽然一些御制掐丝珐琅火盆的上部结构具有镂空设计,但通常是镀金铜材质,而非掐丝珐琅装饰,其他器物亦多如此。然而,在某些器型上,仍可见少量镂空掐丝珐琅装饰。例如,八吉祥之一的“盘长结”便出现在部分乾隆御制掐丝珐琅供器的镂空装饰中,如美国凤凰城艺术博物馆收藏的一件作品(见B. Quette主编,《掐丝珐琅——元、明、清中国珐琅》,纽约,2011年,第271页,编号93)。此外,布鲁克林博物馆收藏的一件乾隆时期掐丝珐琅象驮瓶葫芦组合器(同书,第274页,编号100)上部的凸缘部分也带有镂空装饰,而台北故宫博物院收藏的一对清康熙御制掐丝珐琅瓶,其灵芝纹饰亦呈镂空设计(见《明清珐琅器》,台北,1999年,第99页,编号28)。乾隆时期的一些特殊掐丝珐琅器物亦可见镂空工艺,例如北京故宫博物院收藏的一件战车形掐丝珐琅香炉,其轮子便采用了镂空装饰(见《故宫博物院藏文物珍品大系:金属胎珐琅器》,香港,2002年,第121页,编号117)。尽管体量更为庞大,但与本品最为接近的镂空掐丝珐琅工艺可见于北京故宫博物院收藏的一件18世纪宫廷掐丝珐琅桌,其裙板部分带有镂空装饰(同书,第160页,编号152)。此外,台北故宫博物院收藏的一件乾隆御制画珐琅香薰,其镂空盖亦值得关注(见《明清珐琅器》,同前,第250-251页)。

在宫廷灯具中,一件与本品相类似的例子是北京故宫博物院养心殿内存放的一对三层式掐丝珐琅宫灯(见《清宫生活图典》,北京,2007年,第115页,编号176、177)。此对宫灯同样采用大面积镂空装饰,包括主灯面,其材质为掐丝珐琅,而非本品所采用的丝绸。值得注意的是,北京故宫的宫灯主灯面为长方形,而非本品的正方形,但四角亦呈斜切状,从而形成更精确的八角形轮廓。

本品宫灯上的丝绸绘画展现了18世纪宫廷绘画风格,以田园景色为主题,且每幅画作均蕴含特定寓意。两盏宫灯上的画面在题材和风格上相辅相成。其中,每盏宫灯各绘有一幅白鹭图:一幅描绘两只白鹭在河中涉水捕鱼,岸边有竹石点缀;另一幅则描绘白鹭立于河岸,同样有竹石相伴。白鹭历来是中国艺术家钟爱的题材,广泛见于绘画和玉雕作品。白鹭羽毛洁白,性情耐心等待猎物,象征廉洁公正的官员。此外,白鹭在古时被称为“杜”(duo),而“杜”亦有“多”之意;“食”与“十”同音(shi),而“鱼”与“余”谐音(yu),故白鹭食鱼可寓意“一多十余”,即“多福多财,十全富足”。

两盏宫灯上的两幅画面展现了隐退的士大夫避世修身的情境,他们在乡间悠然自得,欣赏着盛开的莲花。莲花长期以来受到中国文人的喜爱,数百年来频繁出现在绘画与诗歌中。或许最著名的莲花崇尚者便是宋代的理学家周敦颐(公元1017-1073年)。除了他在哲学上的重要著述外,周敦颐还撰写了一篇名为《爱莲说》的短文,文中他将莲花与菊花、牡丹进行比较。他之所以欣赏莲花,是因为莲花“出淤泥而不染”,其花心不杂乱,直立于纤细的花茎之上,无旁枝蔓藤,不争艳夺目,清香淡雅,并且只能远观而不能亵玩。对周敦颐而言,菊花如隐士,牡丹如富贵之人,而莲花则如君子。这两盏宫灯上绘制的楼阁中凝视莲池的士人或许是以周敦颐为原型,但这并不确定,因为观赏莲花是文人雅士普遍的雅趣。例如,清宫廷绘画中便有数幅雍正皇帝坐于楼阁中眺望莲池的画像(见《故宫博物院藏文物珍品全集14:清代宫廷绘画》,香港,1996年,第91页,编号12.1;第108页,编号16.6;第114页,编号17.6;第133页,编号20.6)。

此外,两幅未绘楼阁的莲池画面中,一幅展现了一位士人携童子漫步于桥上,另一幅则描绘了一名渔夫撑船穿越莲池,船上放置着一只装满莲花和荷叶的大瓶。对于中国士大夫而言,将自己想象成江上渔者、过着闲适的生活,是一个反复出现的理想境界。而那只盛满莲花的大瓶,则令人联想到古代文人雅士泛舟莲池、采莲宴饮的风雅之乐。

最后,每盏宫灯上皆有一幅以粉白色木槿花为主题的画面——其中一幅仅绘木槿花,而另一幅则描绘了一只金鸡站立在开满木槿花的岩石旁。木槿花生长于水边,因此它与这些以水为主题的画面相得益彰。木槿在汉语中被称为“木芙蓉”,其中“芙蓉”可谐音为“富(fu)”与“荣(rong)”,寓意“富贵荣华”。此外,木槿又称“拒霜”,是九大秋花之一。中国诗人曾以“醉木槿”形容木槿花,因为它清晨绽放时呈淡粉白色,而至傍晚则逐渐变为深粉色,犹如美人微醺时脸颊泛起的红晕。

在那幅金鸡与木槿花相结合的画面中,金鸡可能象征着宫灯主人的官运亨通。因为在中国古代品阶制度中,金鸡(锦鸡)是文官二品的补服图案。而“雉”在汉语中发音为“zhi”,与“治”谐音,寓意“治理有序”。此外,岩石在中国传统象征体系中代表长寿。因此,这幅画面所蕴含的寓意可能是:在安定祥和的时代,享受富贵荣华与长寿安康。

An Exquisite Combination of the Arts of the Painter and Enameller

Rosemary Scott, International Academic Director, Asian Art

This pair of superb lanterns brings together the skills of the enameller creating delicately reticulated cloisonné stands, with those of the painter on silk creating eight elegant panels through which the flickering light would have shone.

Cloisonné items on which there is extensive reticulation are very rare. While a number of imperial cloisonné braziers have reticulated upper sections, these are usually made of gilded bronze rather than having cloisonné enamel decoration, and this is usually the case with other forms. However, smaller sections of pierced cloisonné can be seen on a selection of shapes. The ‘endless knot’ which is one of the Eight Buddhist Emblems is pierced on some cloisonné imperial Qianlong altar sets, such as that in the collection of the Phoenix Art Museum (illustrated by B. Quette (ed.) in Cloisonné – Chinese Enamels from the Yuan, Ming, and Qing Dynasties, New York, 2011, p. 271, no. 93). The upper extending flange of a Qianlong cloisonné elephant, vase and gourd group in the collection of the Brooklyn Museum (illustrated ibid., p. 274, no. 100) is also reticulated, as are the lingzhi sprouting from a pair of imperial Kangxi vases in the collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei (illustrated Enamel Ware in the Ming and Ch’ing Dynasties, Taipei, 1999, p. 99, no. 28). The wheels on a number of eccentric cloisonné items made for the Qianlong emperor are reticulated, such as those on a censer in the form of a chariot in the collection of the Palace Museum, Beijing (illustrated in The Complete Collection of Treasures of the Palace Museum 43 Metal-bodied Enamel Ware, Hong Kong, 2002, p. 121, no. 117). Although on a significantly larger scale, the reticulated cloisonné work closest in approach to the current lanterns appears on the aprons of an 18th century table in the Palace Museum Beijing (illustrated ibid., p. 160, no. 152). It is also interesting to note the extensively reticulated cover on an imperial Qianlong perfumier with painted enamels in the collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei (illustrated Enamel Ware in the Ming and Ch’ing Dynasties, op. cit., pp. 250-51).

A rare counterpart among court lanterns is a pair of three-storey cloisonné lanterns preserved in the emperor’s private living quarters in the Yangxin dian in the Forbidden City, Beijing (illustrated Life in the Forbidden City of Qing Dynasty, Beijing, 2007, p. 115, nos. 176 and 177). These appear to have extensive reticulation, including on the main panels, which are in cloisonné rather than the silk seen on the current examples. Interestingly, although the main panels on the Beijing lanterns are essentially rectangular, rather than square like the current lanterns, they too have canted corners, rendering them more precisely octagonal.

The delicate painting of the silk panels on the current lanterns reflects court painting style of the 18th century, and, within their theme of bucolic idyll, the subject of each has been chosen to convey a particular message. Each lantern has painted panels which complement in subject, as well as in style, the panels on the other. Each of the lanterns has one panel in which a pair of white egrets is depicted in a natural setting – in one case the birds are wading and fishing in a river with rocks and bamboo at the water’s edge; while on the other panel the birds stand on the river bank, again with rocks and bamboo. Egrets have long been a popular subject for Chinese artists, particularly painters and jade lapidaries. Egrets with their pristine white feathers and the patient way in which they wait for fish, are often seen as symbols of an incorruptible official. While the general word for egret in Chinese is lusi, the ancient name was duo, which also means ‘plenty’. The word for’ to eat’ and the word for ‘ten’ sound the same – shi, while the word for ‘fish’ is yu, which sounds like the word for ‘abundance’. Thus an egret eating a fish can suggest the phrase yiduo shiyu, meaning ‘Plenty and ten abundances’.

Two of the panels on each lantern suggest a scholar-official in retreat from the cares of office, relaxing in the countryside and admiring blossoming lotus. Lotuses have long been admired by Chinese literary men and have appeared in both paintings and poetry for centuries. Perhaps the most famous admirer of lotuses was the Song dynasty Neo-Confucian philosopher Zhou Dunyi (AD 1017-73). In addition to his influential philosophical writings, Zhou was also the author of a short essay entitled Ai lian shuo ‘On the Love of the Lotus, in which he comparers lotuses to chrysanthemums and peonies. His admiration for the flower is based upon the fact that it rises unsullied from the muddy waters, it has no distracting centre, it grows straight on a slim stem without extraneous creeping vines or branches, it has a mild fragrance, and is enjoyed at a distance – not too intimately. To Zhou Dunyi the chrysanthemum was like a recluse, the peony was like an important, wealthy person, while a lotus was like a gentleman. It is possible that one, or both of the scholars seated in pavilions overlooking lotus ponds on panels from the lanterns are supposed to depict Zhou Dunyi. However, this is not certain since this was a popular occupation amongst cultured gentlemen and, for example, there are several court ‘life portraits’ of the Yongzheng Emperor seated in a pavilion gazing over a lotus pond (see The Complete Collection of Treasures of the Palace Museum 14 Qing Dynasty Imperial Palace Paintings, Hong Kong, 1996, p. 91, no. 12.1; p. 108, no. 16.6; p. 114, no. 17.6; and p. 133, no. 20.6).

Of the two panels depicting lotus ponds without pavilions, one shows a scholar strolling across a bridge, accompanied by a young attendant, while the other depicts a fisherman punting his boat across the lotus pond. In the boat is a large vase containing lotus blossoms and leaves. It was a recurring dream of Chinese scholar-officials to see themselves as simple fisherman, spending their days at a leisurely pace on the river. While the large vase of lotuses suggests the elegant boating parties held on lotus ponds, during which lotuses would be collected and placed in just such large receptacles.

Lastly, each lantern has a panel painted with pale pink and white hibiscus – one depicting the plant alone, and the other showing a golden pheasant perched on a rock beside a flowering hibiscus. The inclusion of hibiscus amongst panels which have water as part of their theme is appropriate, since hibiscus naturally grows near water. The Chinese name for hibiscus is mufurong, which provides a rebus for ‘wealth’ fu and ‘glory’ rong. But it is also known as jushuang meaning ‘resists frost’. Hibiscus is one of the nine autumn flowers. Chinese poets have also called the hibiscus zujiu furong or ‘intoxicated hibiscus’ because the flowers open in the morning as pale pinkish white blossoms, but become deep pink in the evening, resembling the flush that wine brought to the cheek of a beautiful woman. On the panel where the hibisicus is combined with a golden pheasant, the latter may suggest an increase in rank for the owner of the lanterns, since the golden pheasant appears on the rank badge of the second highest rank of civil official. The word for pheasant in Chinese is zhi, which sounds like the word for ‘order’. Rocks in Chinese symbolism can stand for longevity. Thus this combination of elements could suggest longevity enjoyed with wealth and glory in a time of order or peace.

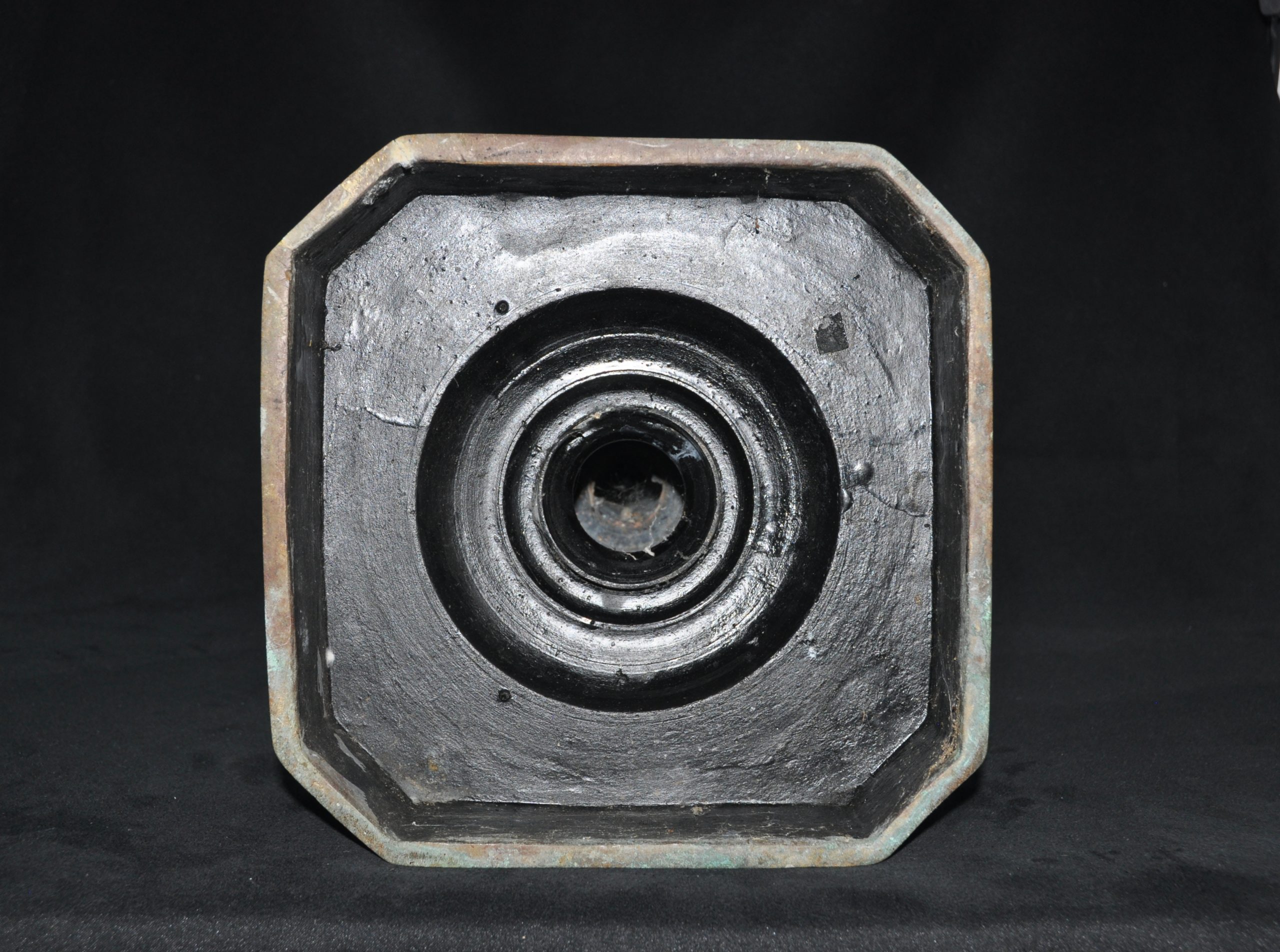

参考:明 十六世紀前期 銅胎掐絲琺瑯夔龍紋尊

功能:陳設,盛裝器

質材:礦物/金屬/銅

說明文:

銅胎,侈口,豐肩,鼓腹,外撇圈足渣斗式尊。除了肩與上腹的內壁露胎外,全器內外均藍地並掐絲紋飾,侈口內飾轉枝番蓮紋,外飾佛教八寶及轉枝番蓮紋,尊內頸部飾一圈縱走平行菊瓣紋、下腹及底為繡球紋;器外頸肩處、腹下方和圈足處,飾仰俯蓮瓣紋,腹面雲紋錦飾夔龍吐蓮紋二,圈足內裝飾轉枝五瓣花葉,底飾番蓮一朵。從掐絲末端捲曲的處理,以及夔龍、蓮瓣的形制與透明釉色等理由,斷定其是十六世前期的文物。

景泰蓝发展史

景泰蓝地位不凡。如古玉般温润,如锦缎般富丽,集绘画、雕刻、青铜、瓷器等中国传统工艺于一身,这就是景泰蓝。

关于景泰蓝的起源,考古界没有统一的答案。一种观点认为景泰蓝诞生于唐代;另一种说法是元代忽必烈西征时,从西亚、阿拉伯一带传进中国,先在云南一带流行,后得到京城人士喜爱,才传入中原。但有一点是学术界公认:明代宣德年间是中国景泰蓝制作工艺优点,并达到了一个新的顶峰时期,“景泰蓝”一词也从此诞生。釉色均肥,丝工粗犷,饰纹丰富。

“景泰蓝”这个称谓最先见于清宫造办处档案。清雍正6年(1728)《各作成做活计清档》记载:“五月初五日,据圆明园来贴内称,本月四日,怡亲王郎中海望呈进活计内,奉旨:……珐琅葫芦式马褂瓶花纹群仙祝寿,花篮春盛亦俗气。珐琅海棠式盆再小,孔雀翎不好,另做。其仿景泰蓝珐琅瓶花不好。钦此。”这一记载,把仿景泰蓝时期的珐琅制品称作“景泰蓝珐琅”,这是所见”景泰蓝”称谓的最早文字记录。

明清两代,景泰蓝在宫廷皇族中兴盛了三四百年,是两朝帝王专享的御用工艺,被誉为“东方奇葩”。

制作工序细分起来有100多道,相当耗费人力心力,无处不体现皇家的尊严和奢华,因而,故有“一件景泰蓝,十箱官窑器”的说法。

参考:佳士得:

十五世紀上半葉 景泰藍琺瑯圓形盒蓋 景泰六字款

31 12月 1969

A RARE CLOISONNE ENAMEL CIRCULAR BOX AND COVER

FIRST HALF 15TH CENTURY, JINGTAI SIX-CHARACTER MARK

成交價 GBP 67,500

估價 GBP 25,000 – GBP 35,000

細節

The cover with a central stylised lotus roundel within eight radiating turquoise-ground lappets each enclosing a lotus flower among scrolling leaves, the base with eight similar lappets, minor infills, old clear lacquer coating

4.7/8 in. (12.5 cm.) diam.

來源

T.B. Kitson, sold Messrs. Sotheby & Co., 21 February 1961, lot 277

出版

Sir Harry Garner, Chinese and Japanese Cloisonn Enamel, pl.19b.

展覽

London, Oriental Ceramic Society, The Arts of the Ming Dynasty, 1957, cat.no. 316

拍品專文

See Sir Harry Garner, ibid., p.57 for a discussion of the six-character mark incised on the base which, similar to other 15th century enamel pieces, is written in a calligraphy which suggests to him a later date.

![[临渊阁]天地一家春](https://www.antiquekeeper.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/cropped-Asian-Art-Wallpaper-Painting3-6-2.jpg)