Description

民国 青花云龙纹水洗

参考:佳士得

18 9月 2014 | 現場拍賣 2872

中國瓷器及工藝精品

拍品 862

A RARE BLUE AND WHITE MING-STYLE ‘ALMS’ BOWL

清 十八世紀 青花蓮紋缽式盌

18TH CENTURY

成交價 USD 30,000

估價 USD 20,000 – USD 30,000

清 十八世紀 青花蓮紋缽式盌

18TH CENTURY

來源

Alfred E. Guntermann (1943-2013) Collection.

狀況報告

We have sought to record changes in the condition of this piece acquired after its initial manufacture.

– mouth rim has been polished

– expected surface abrasion and light scratches

拍品專文

A similar bowl, dated Qianlong period, was sold at Christie’s New York, 24 March 2011, lot 1678.

参考:佳士得

8 11月 2012 | 現場拍賣 7339

中國瓷器、工藝精品及紡織品

拍品 1249

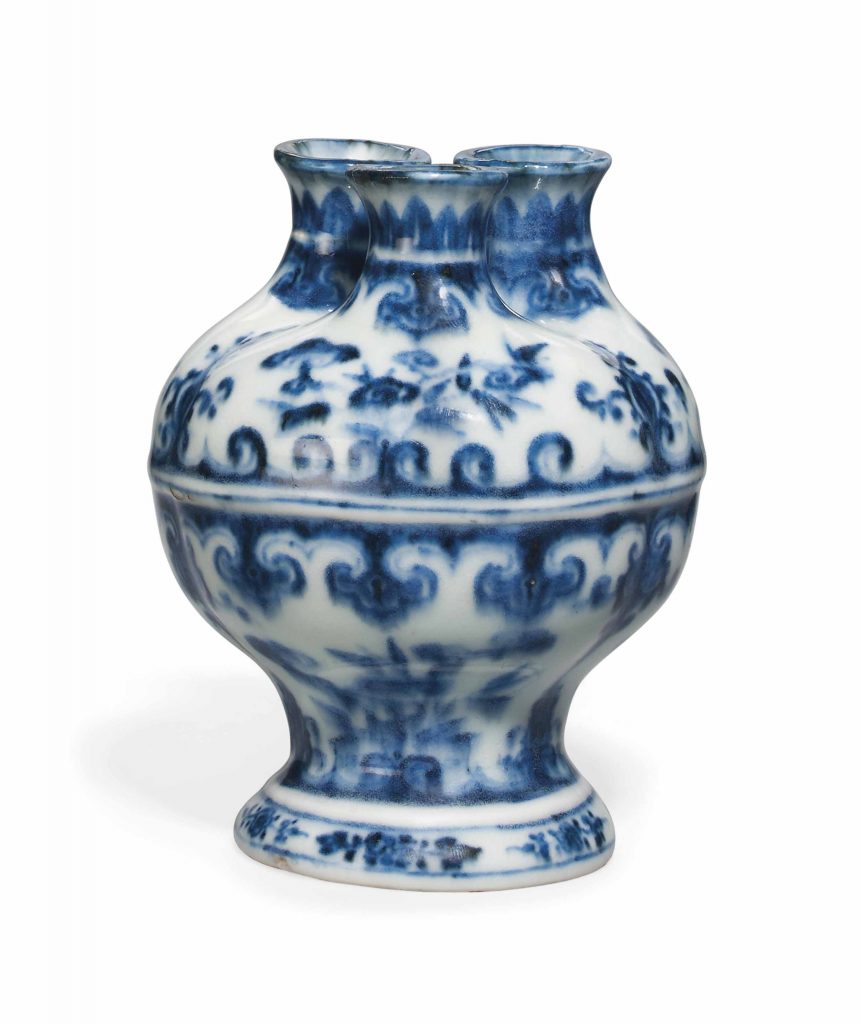

A BLUE AND WHITE ‘FLOWER’ VASE

清十八世紀 青花靈芝紋三頸瓶

成交價 GBP 8,125

估價 GBP 6,000 – GBP 8,000

細節

清十八世紀 青花靈芝紋三頸瓶

參考: 國立歷史博物館 品名:【青花龍紋圓罐】

登錄號:7212

資料類型:瓷器

格式:尺寸:口徑5.5 底徑5

参考: 佳士得 拍賣 14612

中國宮廷御製藝術精品/ 重要中國瓷器及工藝精品

Convention Hall|2017年5月31日

拍品3225

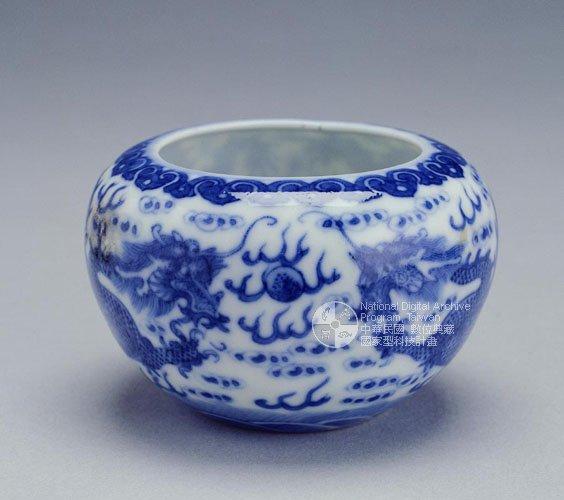

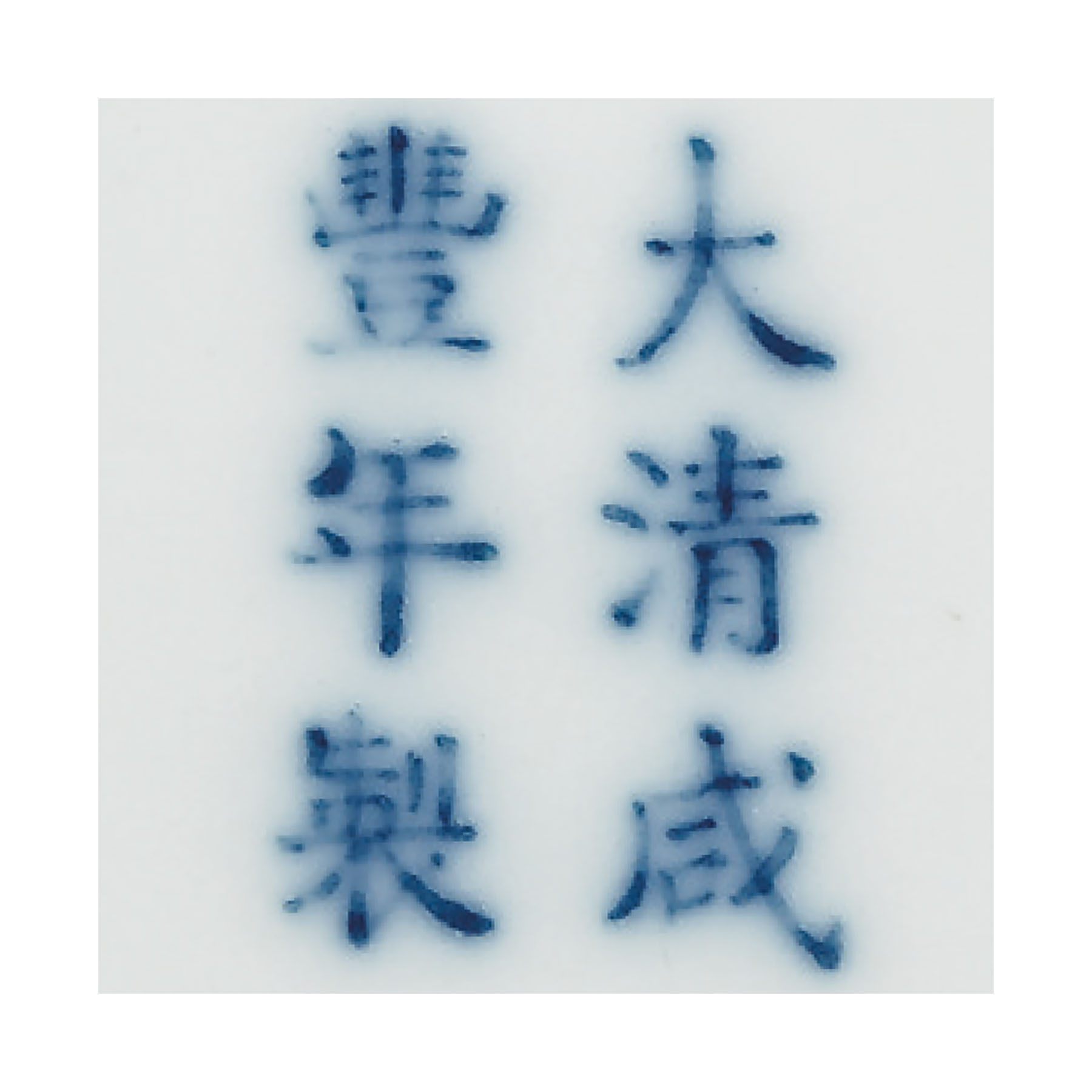

清咸豐 青花雲龍趕珠紋水丞 六字楷書款

XIANFENG SIX-CHARACTER MARK IN UNDERGLAZE BLUE AND OF THE PERIOD (1851-1861)

清咸豐 青花雲龍趕珠紋水丞 六字楷書款

清咸豐 青花雲龍趕珠紋水丞 六字楷書款

成交總額

HKD 237,500

估價

HKD 80,000 – HKD 120,000

清咸豐 青花雲龍趕珠紋水丞 六字楷書款

2 1/16 in. (5.3 cm.) high

來源

日本私人珍藏,2010年10月購自尚雅堂

2011年購自繭山龍泉堂

参考:佳士得拍賣 12290

中國瓷器、工藝品及紡織品(第二部分)

倫敦南肯辛頓|2016年5月13日

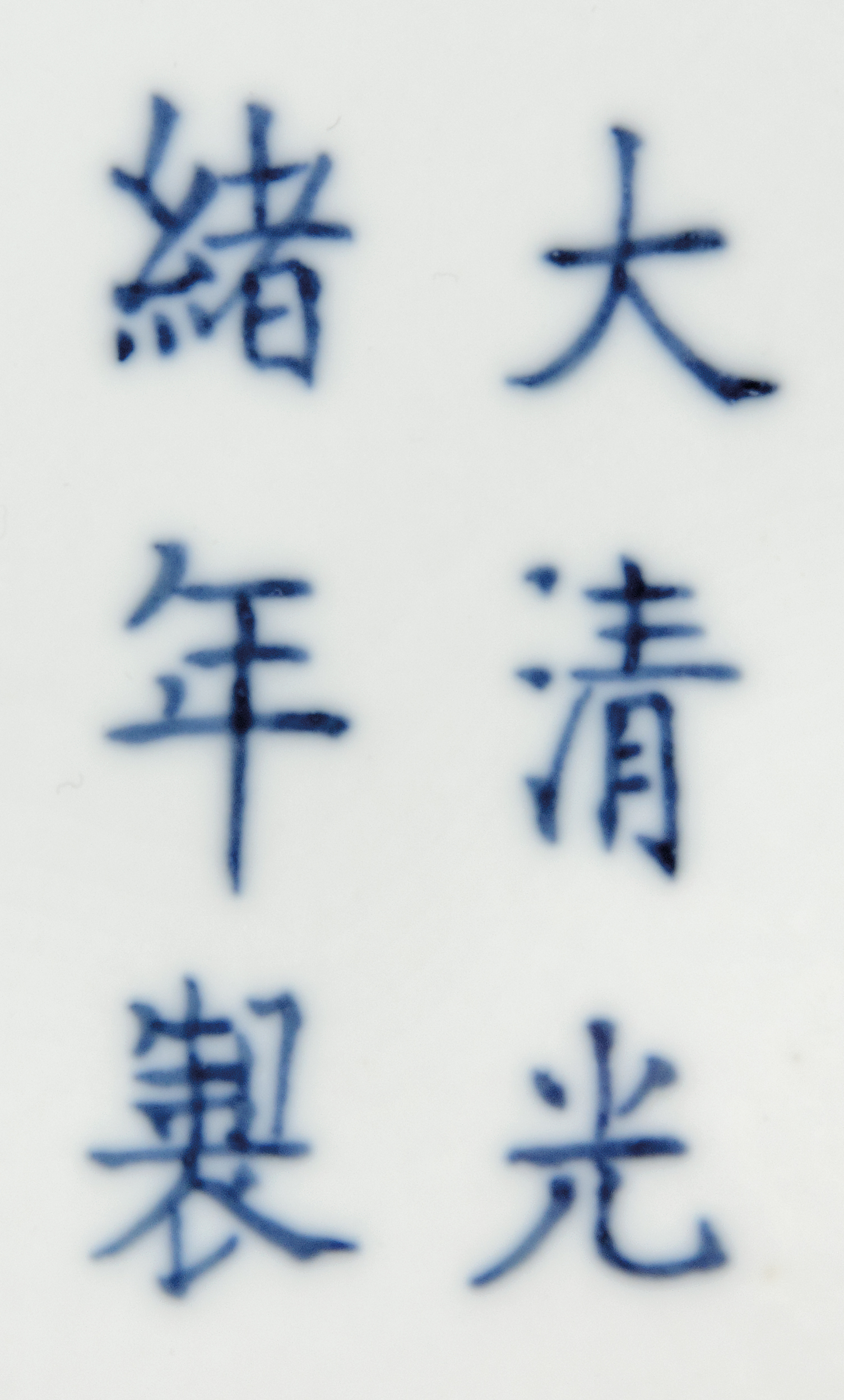

拍品663晚清 青花云龙纹盘

A BLUE AND WHITE ‘DRAGON’ DISH

GUANGXU SIX-CHARACTER MARK IN UNDERGLAZE BLUE AND OF THE PERIOD (1875-1908)

成交總額

GBP 3,000

估價

GBP 2,000 – GBP 4,000

A BLUE AND WHITE ‘DRAGON’ DISH

GUANGXU SIX-CHARACTER MARK IN UNDERGLAZE BLUE AND OF THE PERIOD (1875-1908)

The footed dish is decorated with a pair of five-clawed dragons leaping amidst fire scrolls in pursuit of a flaming pearl, a similar frieze to the exterior.

13 3/8 in. (34 cm.) diam.

來源

Property from the collection of the late Hans J. Christensen (1922-1985).

参考:佳士得拍賣 12548

古今∣佳士得

香港|2016年4月5日

拍品178

清中期 青花雙龍戲珠紋鼻煙壺

清中期 青花雙龍戲珠紋鼻煙壺

清中期 青花雙龍戲珠紋鼻煙壺

成交總額

HKD 56,250

估價

HKD 30,000 – HKD 50,000

清中期 青花雙龍戲珠紋鼻煙壺

参考:中国嘉德四季第53期·迎春拍卖会 > 嘉友藏瓷 > 民国 青花云龙纹洗

拍卖信息

Lot 3989 民国 青花云龙纹洗

估价:1,000-2,000 RMB

成交价: 17,250 RMB (含买家佣金)

尺寸:

直径27.5cm

拍品说明:

“大清康熙年制”款

参考: 0020 50-60年代 青花鱼藻纹水洗

上海道明拍卖有限公司 > 2014年春季艺术品拍卖会 > 民国及现当代瓷器专场

拍品信息

作者 —

尺寸 直径14.2cm

作品分类 工艺品杂项>笔墨纸砚

创作年代 50-60年代

估价 RMB 36,000-45,000

成交价

专场 民国及现当代瓷器专场

拍卖时间 2014-03-27

拍卖公司 上海道明拍卖有限公司

拍卖会 2014年春季艺术品拍卖会

说明 题识:『大清乾隆年制』六字三行篆书款

说明:本洗绘池塘内水草簇拥,水流潺潺,青萍漂浮,游鱼穿梭其间,一幅变化灵动的池塘景色,青花呈色标准。

参考:佳士得拍賣 2368

中國宮廷御製藝術精品

Hong Kong|2007年5月29日

拍品1351|

明宣德 青花缠枝牡丹纹球形水碗

A RARE EARLY MING BLUE AND WHITE GLOBULAR BOWL, QING SHUI WAN

成交總額

HKD 2,040,000

估價

HKD 700,000 – HKD 900,000

A RARE EARLY MING BLUE AND WHITE GLOBULAR BOWL, QING SHUI WAN

XUANDE SIX-CHARACTER MARK IN A LINE AND OF THE PERIOD (1426-1435)

Of well-potted globular form, painted on the rounded sides with a broad band of open blooms including rose, camellia, peony and hibiscus borne on an undulating stem issuing small leaves, above a band of upright lappets above a band of classic scroll encircling the foot, the shoulder with a band of eleven lotus heads on a narrow floral meander below the rim, the interior with a central chrysanthemum roundel

3¾ in. (9.7 cm.) diam., box

來源

Sir Percival and Lady David Collection

Alfred Clark Collection

Spink & Son, 1974

文獻及展覽

文獻

A.D. Brankston, Early Ming Wares of Chingtechen, Hong Kong, 1982, pl. 22 b.

展覽

Oriental Ceramics Society, Ming Blue and White Exhibition, 1946, Catalogue, no. 27

Mostra D’Arte Cinese, Palazzo Ducale Venezia, 1954, Catalogue, no. 639

拍品專文

Globular bowls of this type were known as pure water bowls, qing shui wan. They were used in Buddhist rituals as vessels containing sacred water used to purify the heart.

A number of examples exist in private and museum collections including one in the collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei which is illustrated in Catalogue of the Special Exhibition of Selected Hsuan-te Imperial Porcelains of the Ming Dynasty, National Palace Museum, Taipei, 1998, pp. 60-61; another is illustrted in Chinese Ceramics in the Idemitsu Collection, Tokyo, 1987, pl. 636.

Compare also an example from the E.T. Chow collection sold at Sotheby’s Hong Kong, 19 May 1981, lot 402 and another sold at Sotheby’s Hong Kong, 2 May 2005, lot 508.

編製圖錄及詳情

拍品前備註

Art from a Golden Era

The Reign of the Xuande Emperor (1426-35)

Rosemary Scott

International Academic Director, Asian Art Departments

When the great Qing dynasty emperor Qianlong (1736-95) wanted to praise contemporary works of art, there were four periods with which he chose to compare them, depending on the material – ancient antiquity; the Song dynasty; and the reigns of the Xuande (1426-35) and Chenghua (1465-87) emperors. In his immense admiration for the porcelains of the Xuande and Chenghua periods Qianlong was expressing an opinion shared by generations of connoisseurs from the 15th century to the present day, who have lauded the quality, innovation and artistic merit of porcelains from these reigns.

The Xuande emperor was a particularly interesting and able ruler,(fig. 1) who had an important impact on arts in many media during his reign. While the first Ming dynasty Emperor Hongwu (1368-98) is remembered primarily for defeating the Mongols and re-establishing Chinese rule over the empire, and the Yongle emperor (1403-25) is remembered largely for the expeditionary voyages on which he sent Admiral Zhenghe, and for moving the capital back to Beijing, the Xuande emperor is remembered for ruling over an empire which enjoyed a period of relative peace and prosperity, and as a great patron of the arts.

The Yongle emperor was originally succeeded by his eldest son (Xuande’s father), who took the reign name Hongxi in AD 1425. Hongxi was an able administrator and humane ruler but suffered from ill health and died within a year of his accession. Hongxi was succeeded by the eldest of his ten sons, Zhu Zhanji, who took the reign title Xuande (1426-35). It is interesting to note the parallels between the relationship that Xuande had with his grandfather Yongle, and the relationship the Qianlong had with his grandfather the Kangxi emperor (1662-1722). Even before his father had been named as Yongle’s successor, Zhu Zhanji had attracted the notice of Emperor Yongle. The reasons for this were his martial skills – he enjoyed riding, showed talent in his horsemanship (fig. 2), and excelled at other military accomplishments such as archery. This endeared him to his grandfather who used to take him on hunting trips and even on military inspections, which required that the child travel far from his family in the palace. Once Zhu Zhanji’s father was named heir apparent in 1411, he himself was officially named imperial grandson, and when he was fifteen years old he was taken by Yongle on the latter’s second Mongolian campaign (1).

The Xuande emperor has been described as a perfect Renaissance man (2). He was a warrior: a physically robust man who enjoyed outdoor activities, such as hunting (fig. 3), and had been trained in martial skills since early childhood. However, he had also received education in the Confucian classics from Hanlin academicians from an early age, and after being named imperial grandson he received additional tutoring in the principles of government. The importance that his grandfather attached to such instruction is demonstrated by the fact that his tutor accompanied him even when he was campaigning with the emperor. Zhu Zhanji was, apparently, an able pupil with an excellent memory and keen intelligence, and he was to become an able ruler with a genuine concern for his subjects.

When he ascended the throne in 1426, at the age of 26, taking the name Xuande (Propagating Virtue) as his reign name, Zhu Zhanji proved that Yongle’s confidence in him had not been misplaced. At the start of his reign there was an armed rebellion led by one of his uncles, Zhu Gaoxu, who resented the fact that he himself had not been chosen to be emperor. Xuande took personal command of the army that set out to put down the rebellion, and, when he succeeded, was relatively restrained in the number of rebels he punished severely. The problem of Annamese resistance to Chinese occupation, which had dogged the previous reigns, also clouded the beginning of Xuande’s reign. This too the emperor dealt with in an intelligent way, realistically assessing the situation and eventually ordering the withdrawal of Chinese troops from Annam. The changes that the emperor made to the administration also enhanced the efficiency of the government, although they required his own constant surveillance and when this was lacking in later reigns the power of the eunuchs became too strong. Like his father, the Xuande emperor appears to have genuinely cared for the welfare of the population and his fiscal reforms, as well as the setting up of local grain stores eased the burdens on the people.

Mote and Twitchett have summarised his reign:

‘… the reign was a remarkable period in Ming history, with no overwhelming external or internal crises, no partisan controversies, and no major debates over state policy. The government operated effectively despite the eunuchs’ increasing involvement in the decision-making process. Timely institutional reforms improved the functioning of the state and nourished the welfare of the people, basic requirements of good government. Not surprisingly, in later times the Hsuan-te reign was remembered as the Ming dynasty’s golden era. (3)’

Added to this, the Xuande emperor wrote admirable poetry, as can be seen from the Ming Xuanzong Huangdi Yuzhiji (Collected Poems of the Ming Emperor Xuanzong [Xuande]), and was quite an accomplished artist, who often signed his paintings ‘playfully painted by the imperial brush’ (fig. 4). The emperor showed notable skill in his paintings of flowers, birds and animals, paying particular attention to the texture of fur and feathers. This interest in texture can clearly be seen in his painting of Gibbons at Play (fig. 5) in which the soft, woolly appearance of the gibbons’ fur is contrasted with the solidity of the rocks and the precise brush strokes used to depict the bamboo. It can also be suggested that the protective way in which the mother gibbon is shown holding her child reflects the compassionate side of the Xuande emperor’s nature. However, the choice of subject in this painting has wider connotations. Gibbons and other simians were a popular subject amongst painters, and this example may be compared with Mu Qi’s (fl. mid-13th century) famous painting of a ‘Monkey Mother and Child’, in the Daitokuji, Kyoto (4). In Buddhism monkeys are regarded as symbols of human life, and, as Barnhart has pointed out, it is no coincidence that the emperor’s painting seems to depict two parents and a child (5). San yuan (three gibbons) also provides a rebus for triple success, and would therefore be a suitable gift on the occasion of some scholarly achievement or an official promotion. This choice of subject is not surprising, since the inscriptions on a number of Xuande’s paintings indicate that they were given as gifts of members of the imperial family or to government officials or to military commanders.

Although it has been suggested by some authors, such as Shi Shouqian, that the emperor’s painting demonstrates close links with popular culture, essentially the style of painting seen in Xuande’s extant works is an orthodox style, in the spirit of scholar-painters, and respecting the traditions of the Song dynasty. It seems likely that both in his own artistic achievements and in his patronage of other artists the Xuande emperor was emulating, to some extent, the great Song dynasty imperial artist and patron, Emperor Huizong (1101-1125). Among the artists of his own era, whose work influenced the Xuande emperor are Sun Long (active first half of the 15th century) and Xia Chang (1388-1470). The latter was famous for his bamboo painting and it is perhaps no surprise that bamboo appears often in Xuande’s own works (fig. 6). It was Xia Chang who was later the author of the ‘Veritable Record of the Xuande Reign’.

Xuande was the first Ming emperor to be a really serious patron of the arts. His three great areas of imperial patronage were in court painting, building projects, and the manufacture of fine porcelains, in which he took a keen personal interest. In the area of painting he replaced the system by which painters simply had loose links with one of the administrative bureaux or directorates, and instigated a more systematic structure of recruitment by examination. Appointed painters were then given ranks and salaries, and had opportunities for promotion. They were appointed to duty in the Renzhi Hall, and the latter, due to the number of painters there, was known informally as the Huayuan, or Painting Academy.

Although the Hongxi emperor had contemplated moving the capital back to Nanjing, the Xuande emperor decided to remain in Beijing, partly to be able to keep a closer eye on the northern borders. The Yongle emperor had initiated the building of the Forbidden City and moved the court to Beijing in 1421. The Xuande emperor, therefore, employed many painters and other craftsmen on projects within the palace. The artist Shang Xi (active 2nd quarter of the 15th century) from Henan province, for example, was probably initially a mural painter, and indeed some of his works on silk which have been preserved in the Palace Museum are large enough to be murals (see fig. 3). His work was much appreciated by the emperor, who awarded him the rather incongruous title of Commander of the Imperial Guards (6). Among Xuande’s other building projects was the embellishment of the Imperial Ming Tombs, for which he ordered magnificent columns, and also the largest marble archway in China (7).

An imperial foundry for the production of fine bronze and copper vessels is also believed to have been established in the Xuande reign. There is a catalogue, the Xuande yi qi tu pu, (Illustrated Catalogue of the Ritual Vessels of the Xuande Period), which is supposed to reproduce a 1428 imperial decree ordering bronzes for the court, following a gift of 39,000 catties of copper from the king of Thailand (8). Rose Kerr has discussed this catalogue at length, and points out that the decree is not mentioned anywhere in the official Ming history. She points to discrepancies in the dating of the preface and postscript, and the problems attributing the pieces illustrated (9). What is not in doubt, however, is the high esteem in which bronze vessels of the Xuande reign have been held by connoisseurs of later periods. Xuande censers in particular are frequently mentioned by writers of the 16th and early 17th centuries, and it may well have been this admiration of Xuande bronzes that led to the production of the fake catalogue, Xuande yi qi tu pu.

It is, however, the Xuande emperor’s enthusiastic patronage of lacquer and porcelain that is particularly celebrated in the current volume. Although there is no evidence of an official lacquer workshop in Beijing itself before the end of the Xuande reign, it would seem that there was some official supervision of the work carried out in lacquer workshops further south. This supervision was probably linked to a department of the Imperial Household. It would appear that the Xuande emperor, like his grandfather, ordered a considerable amount of vermilion lacquer furniture decorated in qiangjin (incised gold) technique for use in the Imperial palace, and also items decorated in this technique to be sent as gifts to foreign rulers. Lacquers decorated using the tianqi (filled-in lacquer) technique were also appreciated by the Xuande emperor, who ordered items made in this way for the court. However, it is carved lacquers for which the Xuande reign is justly famous. As Sir Harry Garner has said: ‘The carved wares of the fifteenth century are, without question, the finest of all carved lacquer wares.’ (10) Certainly they have consistently been the most admired by collectors, and it is interesting to note that the Qing dynasty Qianlong emperor mentioned Xuande lacquers no less than twelve times in his poems (11). The carved lacquers from this reign are appreciated for the extreme care taken in their production – from the careful preparation of the base material to the meticulous application of each thin layer of lacquer. It has been estimated that some of these carved lacquer had more than one hundred layers, and would have taken some two years to complete. A number of the carved lacquers made for the court bear well written six-character reign marks embellished with gold lacquer, and this use of reign marks is something they share with porcelain made for the Xuande emperor.

While rather messy reign marks were scratched into the bases of some Yongle lacquers, and a small number of Yongle porcelains bear marks in archaistic script, both the lacquers and porcelains of the Xuande reign bear clearly written reign marks – in the case of porcelains, on a regular basis. Some scholars have suggested that the style of the reign marks on Xuande porcelains was based upon the emperor’s own calligraphy. This seems to be borne out by comparison of the Xuan and de characters inscribed on the emperor’s ‘Gibbons at Play’ (see fig. 4), painted in the first year of his reign, with the characters as they appear on porcelain.

The Xuande emperor certainly took a very keen interest in the porcelain produced for his court, and according to the Fouliang Xian Zhi (Fouliang County Gazetteer) it was in his reign that officials were first sent to Raozhou to supervise the production of imperial porcelains. Orders were issued for imperial porcelain from the first year of his reign. Traditionally a new emperor suspended building projects and the firing of imperial ceramics as part of the mourning rituals, but the Xuande emperor does not seem to have observed this custom, even though he was still in mourning for both his father and his grandfather. The Ming Shilu (Veritable Records of the Ming Dynasty) states that in the 9th month of the first year of his reign, the court issued an order for white sacrificial wares. Interestingly, between 1426 and 1430, it was mainly white wares that the emperor presented either to those of his subjects he wished to honour, or to foreign governments such as the Korean court.

Both the Xuande emperor’s personal interest in porcelain production and his determination to stamp out official corruption can be seen in an incident related in the Ming Shilu. In 1427-8 the supervisor of the official factory at Raozhou (Jingdezhen), Zhang Shan, was found guilty of corruption and brutality to his subordinates. The emperor ordered that he should be beheaded. Production at the Imperial kilns at Jingdezhen was huge in the Xuande reign, and it has been estimated that at one time there were 58 kilns working for the court. The Da Ming Huidian (Institutions of the Great Ming Dynasty) records that in 1433 some 443,500 items of porcelain were made for the court.

The quality and variety of the porcelains made for the Xuande emperor are a testament to his patronage. The body of Xuande porcelains was low in calcium and high in potassium, which facilitated an increase in translucency. The glaze was rich and lustrous, while the underglaze decoration demonstrated complete mastery of painting in cobalt on porous porcelain. The Xuande reign is also unusual in the fact that both large and small pieces are equally well made. The range of shapes is also considerable, and historical texts mention so many forms produced in this period, that it has not yet been possible to identify all of them. Those Xuande porcelains that have survived in international collections range from large jars to tiny bird feeders. Xuande porcelains of a variety of colours and decorative techniques have been discovered. The copper red monochromes of the Xuande reign have, arguably, never been surpassed. The early version of doucai provided the basis on which the Chenghua doucai techniques could be built. The Xuande emperor’s interest in antiques can be seen in the imitations of Song dynasty glazes which were produced at the Imperial kilns during his reign. However, it is the porcelains decorated in underglaze blue for which the Xuande reign is particularly renown. In the Guang Zhiyi (Gazetteer of Guangdong), the Ming dynasty writer Wang Shixing noted: ‘Xuande and Chenghua porcelains are the best in our dynasty, and the best of Xuande porcelains is the qinghua [underglaze blue]… .'(12) Even today, few would argue with that assessment.

1. F. W. Mote and D. Twitchett (eds.), The Cambridge History of China, Volume 7 – The Ming Dynasty, 1368-1644, Part I, Cambridge University Press, 1988, p. 285.

2. A. Paludan, Chronicle of the Chinese Emperors, Thames & Hudson, London, 1998, p. 169.

3. Mote and Twitchett, op. cit.., p. 304.

4. J. Cahill, Treasures of Asia – Chinese Painting, Skira, Geneva, 1972 edition, p. 97.

5. R. M. Barnhart, ‘The Return of the Academy’ in Possessing the Past – Treasures from the National Palace Museum, Taipei, Wen Fong and James Watt (eds.), Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1996, p. 339.

6. Yang Xin, ‘The Ming Dynasty (1368-1644)’, in Three Thousand Years of Chinese Painting, Yale University Press, New Haven & London, 1997, p. 202.

7. A. Paludan, op. cit., p. 169.

8. 39,000 catties would have been the equivalent of approximately 23 tons.

9. Rose Kerr, Later Chinese Bronzes, Bamboo Publishing, London, 1990, pp. 18-9.

10. Sir Harry Garner, Chinese Lacquer, Faber & Faber, London, 1979, p. 80.

11. ibid.

12. Catalogue of the Special Exhibition of Selected Hsuan-te Imperial Porcelains of the Ming Dynasty, National Palace Museum, Taipei, 1998, p. 41.

THE PROPERTY OF A GENTLEMAN

![[临渊阁]天地一家春](https://www.antiquekeeper.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/cropped-Asian-Art-Wallpaper-Painting3-6-2.jpg)